- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first book of fiction is a little sub-genre with a number of readily recognisable features. It’s loosely structured and tends to be episodic, without much of a plot. It’s at least partly about love and sex, preferably of an obsessive or otherwise significant kind. And it’s at least partly autobiographical. If it’s already a bad book, then these things do tend to make it worse, but if it isn’t, then they don’t necessarily detract; it’s not a value judgement, just an observation.

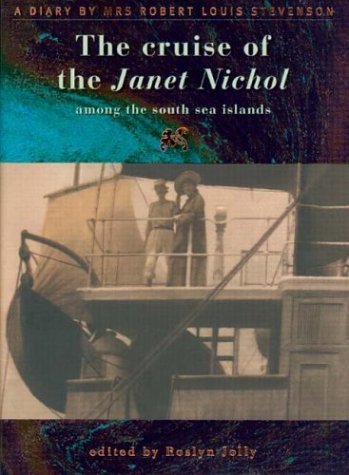

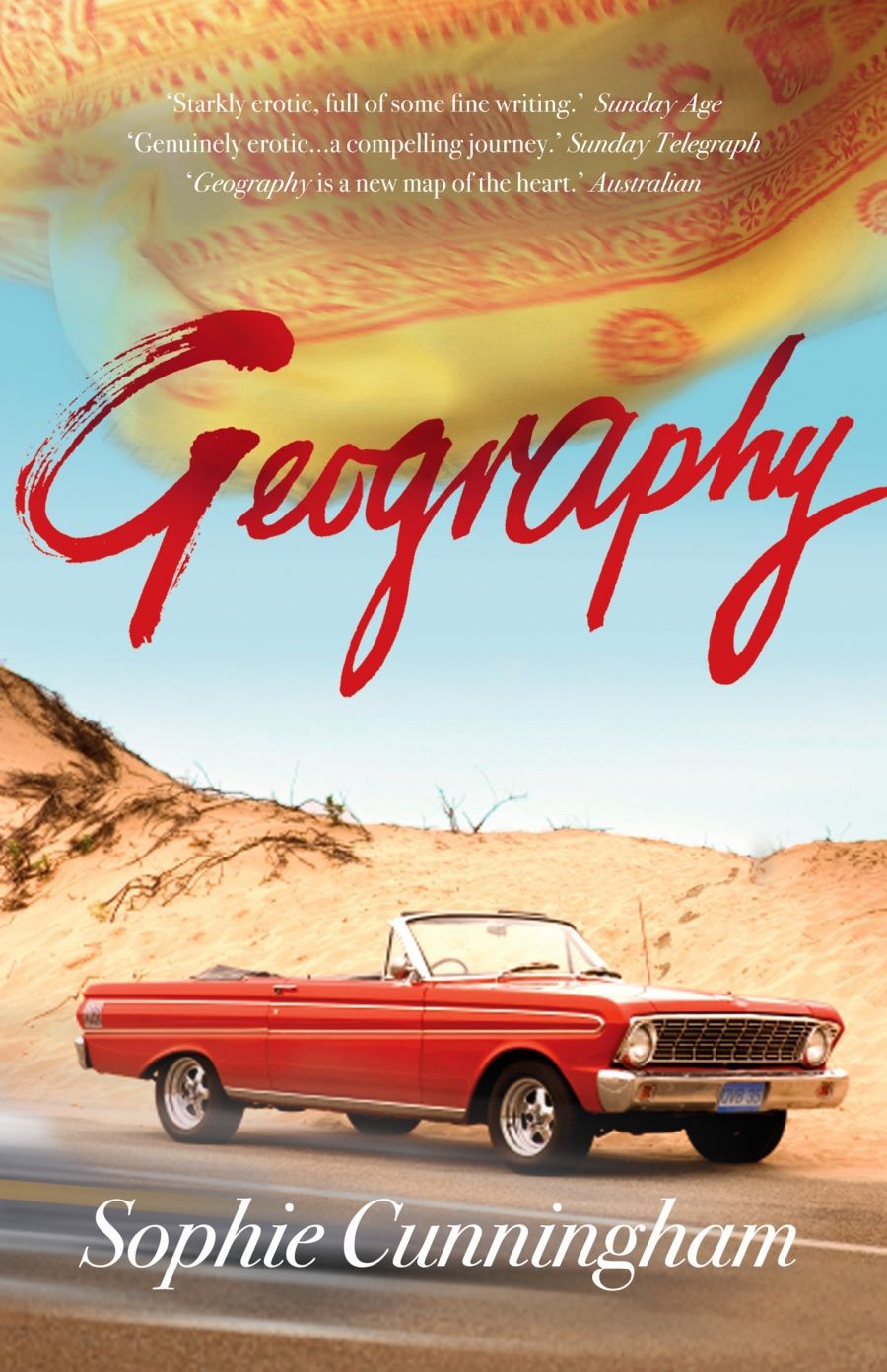

- Book 1 Title: Geography

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $25 pb, 208 pp

The first book of fiction is a little sub-genre with a number of readily recognisable features. It’s loosely structured and tends to be episodic, without much of a plot. It’s at least partly about love and sex, preferably of an obsessive or otherwise significant kind. And it’s at least partly autobiographical. If it’s already a bad book, then these things do tend to make it worse, but if it isn’t, then they don’t necessarily detract; it’s not a value judgement, just an observation.

Read more: Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews 'Geography' by Sophie Cunningham

Write comment (0 Comments)