- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

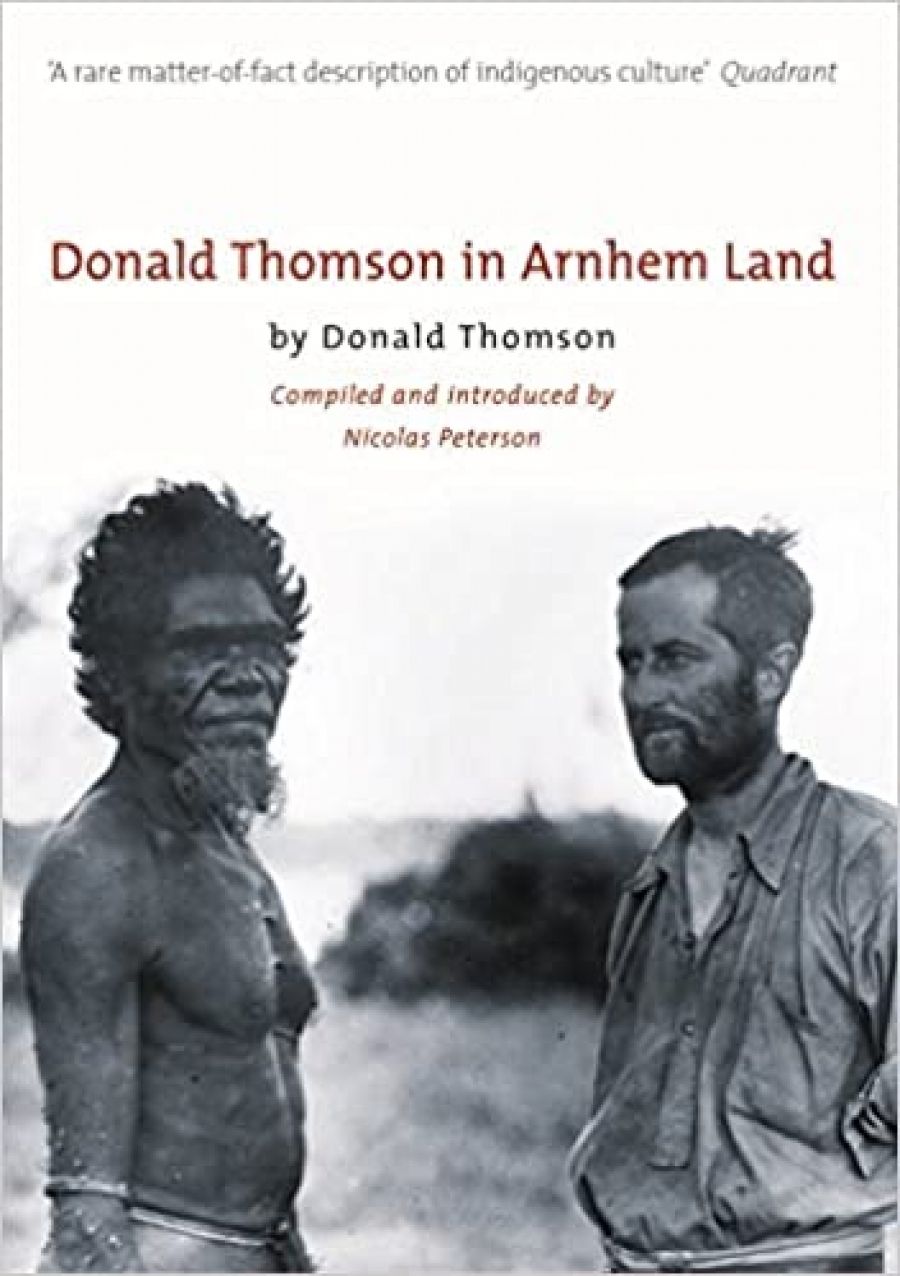

Donald Thomson’s stature as a great Australian and a champion of Aboriginal rights is confirmed by this engaging compilation. Thomson was also a world leader in ethnographic field photography. Published first in 1983, this revised edition contains a gallery of eighty additional evocative, annotated images of vibrant people and their ways of living. Today’s evaluation contrasts with that around the time of Thomson’s death in 1970, when his reputation reached its nadir. Most anthropologists then disparaged his work, few appreciated the richness and complexity of his collections, while only one academic book testified to his credentials.

- Book 1 Title: Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $49.95 hb, 264 pp

In Thomson’s later years, I knew him as a contrary and frequently cranky loner. He was secretive, difficult to meet, sensitive to criticism and convinced that the anthropology profession contrived against him. Certainly, some members proved stubbornly territorial, and he roused the durable enmity of A.P. Elkin, that influential controller of purse strings, appointments, and reputations. As a habitual public critic of the Victorian government’s Aboriginal policies, Thomson received little local support during those locust years of neglect. Because anthropology received little priority at Melbourne University, Thomson experienced insecurity of tenure and remained isolated from interstate peers. He relied upon the patronage of sympathetic medical professors. When his priceless seven thousand metres of movie film were destroyed at a government repository in 1946, he blamed arson, suspecting a rival’s match. This tragedy bolstered his sense of grievance and exclusion.

Yet Thomson dealt essentially with the highest authorities – prime minister, chief justice, vice chancellor – sometimes achieving results, such as when the RAAF dropped supplies in the desert. The long-suffering university administration accommodated him; eventually, a Parkville house became his office. It was an Aladdin’s cave, but few knew of its momentous contents and fewer still viewed them.

Following Thomson’s death, this treasure house was opened through the enlightened cooperation of his widow, Dorita, and university and museum authorities. This collection is unrivalled in Australia. No other anthropologist collected artefacts, identifying them in Aboriginal and English words, photographed them in context of manufacture and use, documented and cross-referenced objects, field notes and photographs. The result was more than 5,700 artefacts, almost 11,000 negatives, and 4,500 pages of detailed field notes, chiefly documenting societies in Cape York (1928–33) and eastern Arnhem Land (1935–37, 1942–43). Now conserved and curated by Museum Victoria, this arrangement ensures the rich heritage in perpetuity for Aboriginal people and others. The editor correctly claims this book to be ‘a visual ethnography’.

Nicolas Peterson was ideally qualified as editor, having worked in Arnhem Land on material culture and subsistence since the 1960s. He has strung together in chronological format Thomson’s documents, many of them official reports. Recovered from oblivion are such themes as Thomson’s role in wartime Arnhem Land, when he organised fifty Aboriginals as front-line guerrillas. The Cape York collections merit comparable treatment.

Peterson notes Thomson’s personalised style. His journalism was so successful that academics often wrongly dismissed it as worthless popularisation. Literally a prophet in the wilderness, Thomson made far-reaching and sympathetic recommendations concerning Aboriginal welfare and administration. They fell upon deaf official and anthropological ears. His blunt attitude and documentation proved so unwelcome in Queensland that, with the premier’s tacit support, Presbyterian mission authorities barred his return to Cape York in 1961. Ironically, overseas honours showered upon him.

A well-published field naturalist, Thomson supplemented his Melbourne science degrees with a Sydney anthropology diploma. However, he never approached Aboriginal society in the mechanistic structuralist manner of his mentor, RadcliffeBrown. Unfashionably, he documented subsistence economies and ecology. His human subjects were not remote analytical specimens, but vibrant individuals, whose complex society Thomson appraised with sympathy and affection. To hear him talk enthusiastically, he found much nobility in other peoples’ savages. His trust was returned by the people among whom he moved freely. This occurred at a time when reprisal expeditions were advocated for the homicide of a few Japanese sailors and a policeman rapist. Critics assumed that Thomson would be killed, but single-handedly he proved the rational humanity of this feared race.

Despite disdainful social anthropologists, Thomson’s research appealed to later archaeologists. In 1939 he published an article in a British archaeological journal, resulting from his year at Cambridge. He demonstrated relationships between Cape York’s seasonal extremes and the adaptive subsistence cycle. An archaeologist excavating different seasonal campsites of the same people could infer that the uncovered relics belonged to distinct cultures. This perceptive case study so influenced archaeologists during the 1960s that, when writing Thomson’s obituary, I praised him as ‘the archaeologists’ anthropologist’.

Peterson opens with an informative biographical sketch, although full justice to Thomson’s adventurous and combative career awaits detailed study. The other chapters reproduce Thomson’s accounts, tracing his Arnhem Land involvement between 1935 and 1937, together with his wartime Special Reconnaissance Unit. Only hinted at here are the sometimes frosty relations between his Aboriginal unit and the Katherine-based North Australian Observation Unit. This merits research, particularly as NAOU was commanded by W.E.H. Stanner, another anthropologist.

Thomson’s characteristic durability, even foolhardiness, under extremely arduous conditions emerges clearly. Brave in the field, he proved equally resolute with officialdom. Thomson stated his terms for entering Arnhem Land following the near hysteria in the wake of the police and Japanese killings. In Darwin, Judge Wells sentenced one elder to death and three sons of prominent elder Wonggu to life imprisonment. Following a High Court appeal, Thomson escorted the sons back to Caledon Bay and Aboriginal approbation. Sir Colin McKenzie lobbied Thomson unsuccessfully to collect Aboriginal skulls for his Institute of Anatomy. Subsequently, McKenzie confronted him in tandem with the Interior Department’s Secretary, his expedition sponsor. Thomson remained adamant. ‘As a matter of fact,’ he responded, ‘I feel that Judge Wells is in a better position to collect skulls for the Commonwealth Government than I am.’

I belong to the generations of historians raised on the tenet of source authenticity, but Peterson follows a different doctrine. His preface offers a blanket explanation for his handling of Thomson’s text. Avoiding an ‘exhaustive or depersonalised account’, the editor has altered ‘certain phrasings to protect Thomson from anachronistic criticism’, omitting words which today imply ‘a jarring and unpleasant connotation’. This is more than political correctness. This version lifts Thomson’s prose from its intellectual context, certainly producing a more fluent text. I am concerned, however, that this ‘improved’ text will be quoted as authoritative Thomson. For example, a comparison between this text and his official wartime report reveals major excisions. This clarifies and avoids repetition, but surely each ellipsis required the conventional three full stops. In the interests of lucidity and aesthetics, therefore, readers are unaware of what Thomson really wrote. Fewer than five pages of notes and sources hardly compensate.

This Miegunyah Press imprint is attractively presented. However, as the many photographs are the essential feature of this revised edition, it is unfortunate that pages were saved through reducing the size of images. (Compare the magnificent full-page goose egg-hunting scene in the first edition with that on page 155.) Even so, this book is a rewarding read, a pictorial treat and a tribute to a significant Australian.

Comments powered by CComment