- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What’s a nice girl called Anastasia doing in the Whangpoa River? Maybe she’s the daughter of the last tsar who everyone thought was dead, or maybe it’s just a girl who looks like a Russian princess and happens to have the same name. If the proposition sounds familiar, be assured by Colin Falconer that Anastasia Romanovs were thick on the streets of Shanghai after the White Russian diaspora of 1917–18.

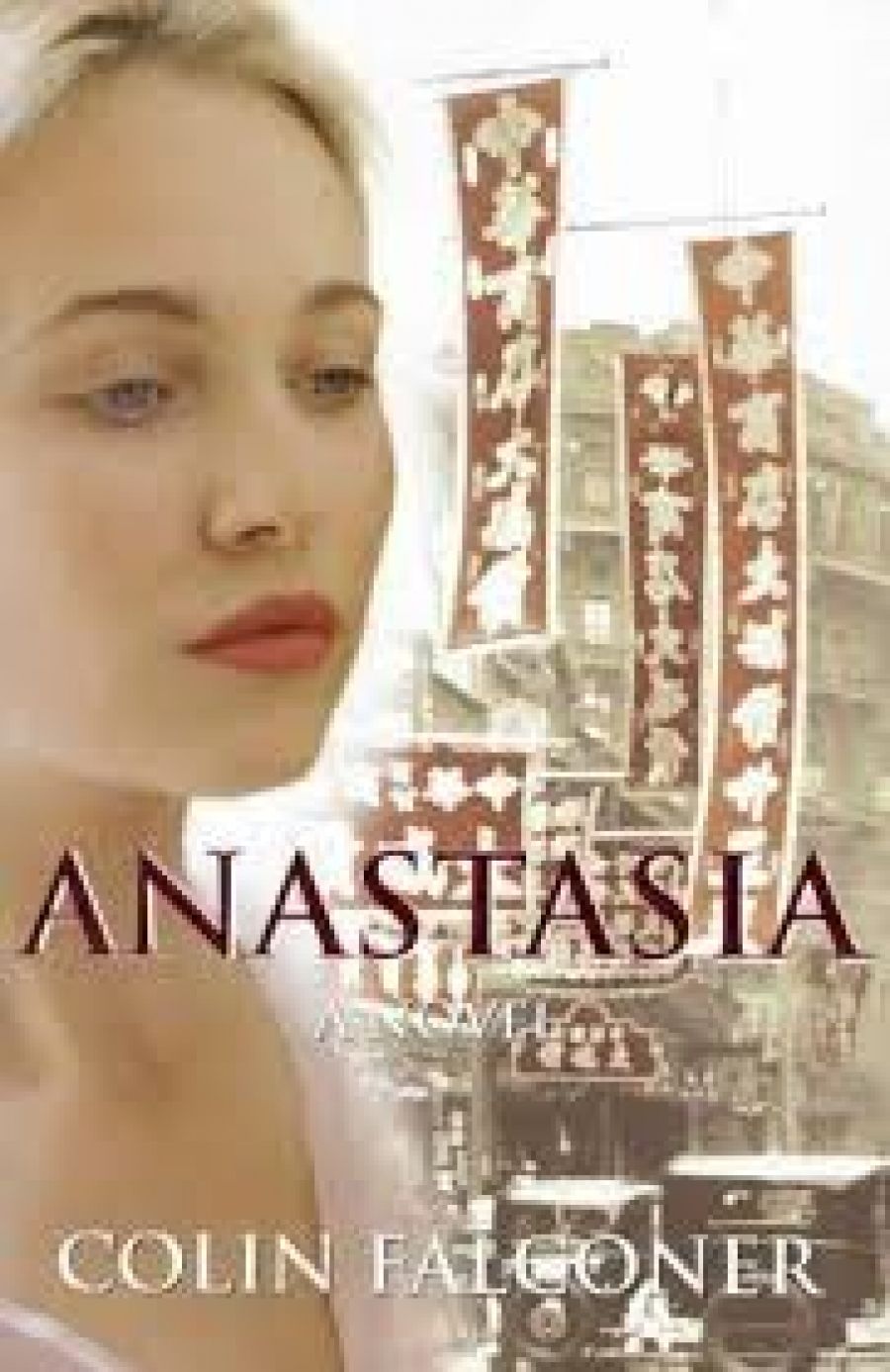

- Book 1 Title: Anastasia

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Bantam, $25.95 pb, 372 pp

Seeing herself as nothing but a taxi girl, and suffering from trauma as well as amnesia, Anastasia at first shrugs off any notion of royal identity, thus winning the approval of the sceptical reader. Soon, however, she succumbs to acting the puppet, and the interest switches to events that link the jaded journalist and the putative princess to the unscrupulous men who are determined to use her for their own gain. There is no lack of colourful period background, even if the central tease is anachronistic. Falconer’s homework backgrounds a plot that moves chronologically over eleven years, from the Romanov assassination in 1918 to the Stock Exchange crash of 1929, and geographically from Ekaterinburg to Shanghai and back again, by way of Berlin, London, New York, and Sverdlovsk (as Ekaterinburg became in Soviet times).

Michael, meanwhile, has fallen heavily for Anastasia, but refuses to take advantage of her, sexually or financially. Not so the predators. Two unsavoury characters come forward to cash in on the girl’s presumed status, their strongman assurances and the enjoyments of the high life almost persuading her of what in her heart she still doubts. The unfortunately named Count Andrei Sergeiovitch Banischevski (unfortunate because Falconer has not extended his historical and geographical research to Russian transliteration: Sergei-o-vitch botches Sergeevich, impossibly) takes her to Berlin to stake her claim. When things go wrong with Banischevski, Michael, working coincidentally in the same city, saves Anastasia all over again and takes her back to London, where they set up together. Yet their relationship remains contorted, and Anastasia is swept off by a new believer in her royal heritage, this time to New York. It would be inexcusable to give away the ensuing vicissitudes.

Readers who are so pedantic as to be irritated by details beyond plot, such as sloppy writing or a lack of subtlety in the characterisation, may find the racy twists and turns an inadequate compensation. You may shy at an arc being circumscribed rather than described, the passive use of ‘disappeared’ (in 1923), the notion of a ‘face of such ethereal beauty it could have been carved from marble’, ‘attentions’ when only the singular is meant, a London apartment that starts with two bedrooms but ends up with only one, and the ‘diseased [jaundiced?] eye’ that Michael casts on the New York milieu. Clichés such as the hero’s crooked grin and Anastasia’s ever-startling blue eyes go into the second category, alongside Michael’s rakish attraction and noble disdain for anything tainted by money (including his father). A third irritation is the way clues and coincidences beggar probability: the false Anastasia is given a deformed big toe and a white scar, just like the real princess; Michael’s small smattering of Russian, picked up in Shanghai [sic], is nevertheless good enough for him to eavesdrop a rapid conversation. Yet none of this jars as frequently as a stylistic idiosyncrasy endemic to Falconer’s prose: the joining of main clauses by a comma. He seems to have declared war on the word ‘and’. Do such details matter? They did to me. This novel’s dramatic action and arresting locales may while away a plane trip, but the life-after-death of the real Anastasia was better served by the 1956 film that starred Ingrid Bergman.

Comments powered by CComment