- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the Australian government urged older workers to delay retirement, some observers saw this as ‘wedge’ politics. One ageing media personality joked about younger women refusing to have babies sufficient to care for him in his dotage. For electors, the falling birth rate may be a controversial economic issue, but for some couples, and especially women, decisions about procreation are not theoretical exercises but painful personal dilemmas.

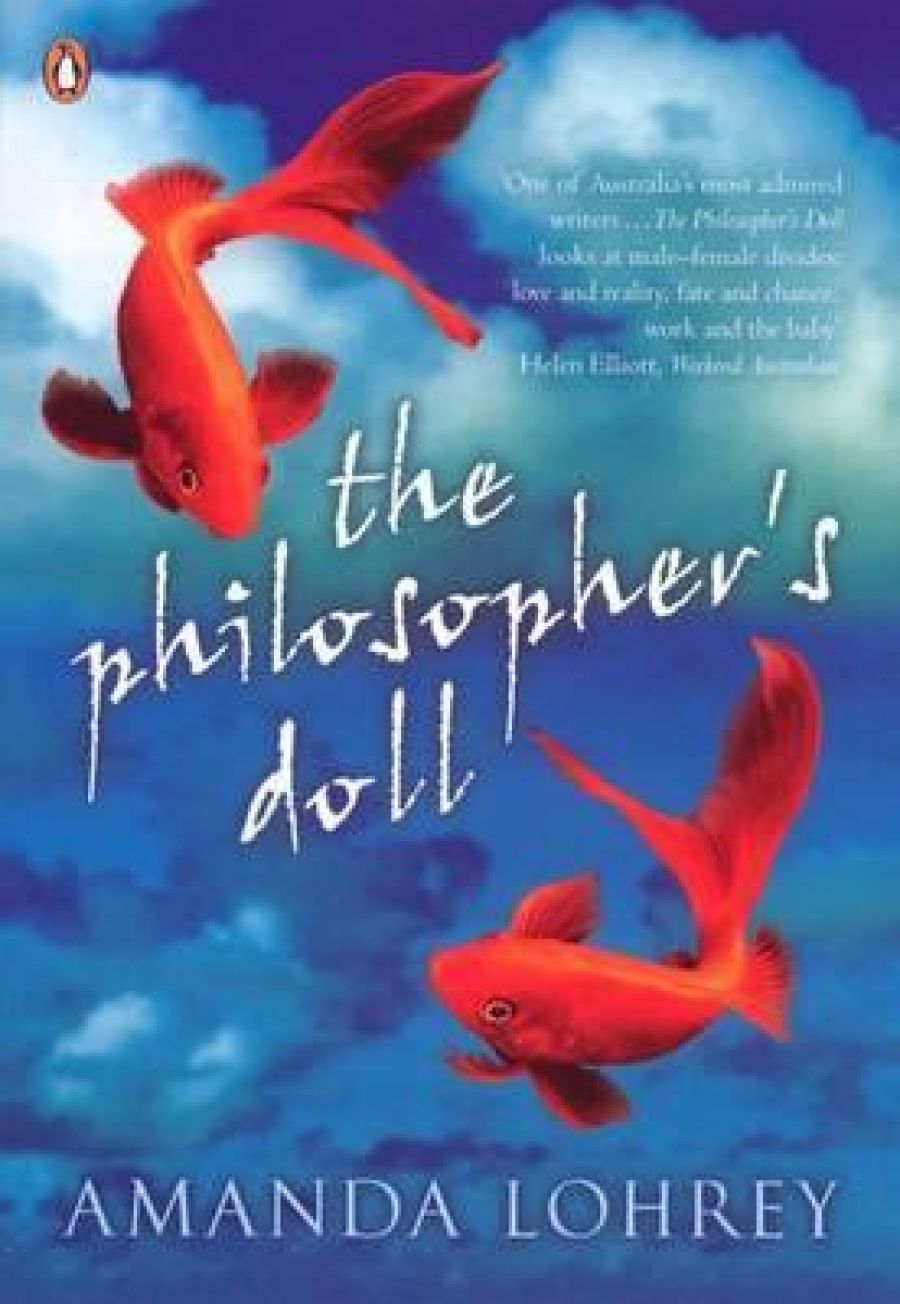

- Book 1 Title: The Philosopher’s Doll

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 pb, 309 pp

Lohrey’s fine ear for dialogue makes the inner thoughts and the verbal interactions of the protagonists crisp and natural. Lindsay might be ‘a philosopher … adept at laying out all the many paths of reasoning, for and against’, but Kirsten is a counsellor, and better understands relationship dynamics. At first sight, it seems that Lohrey’s major theme is a simple male/female dichotomy between head (rationality) and heart (emotion). But Lohrey uses the fictional relationship between Lindsay and Kirsten to explore broader issues, including the role of the human will and its place in the tensions between random events and determinism, between biological imperatives and individual responsibility.

Lohrey is so perceptive that there is nothing superfluous in this superbly structured novel. Every event, every word is necessary and there are constant echoes that remind the reader of the complexity of the plot and the sophistication of the author’s technique. Lindsay gets notes from Sonia, a student who pledges her love, but eventually she says that she will apply for another supervisor – ‘a demonstration of the truth of one of his gut instincts: in nine cases out of ten, if you do nothing, a situation will resolve itself’. There is nothing random about Lohrey’s writing, however, and nothing is left to chance. As Lindsay drives to buy a dog for Kirsten, he remembers his nephew describing the problem involved in designing a computer programme to replicate the human mind – it cannot handle randomness. Lindsay also encounters a procession of people carrying Ganesh, the Hindu God said to remove obstacles (though Lohrey does not patronise the reader by spelling this out).

Meanwhile, Kirsten berates herself: ‘How had she, a practical woman, become trapped in such a philosophical conundrum?’ Was she suffering from ‘decidophobia’? Worse: ‘Of all the feelings in her life that cause her pain, the thing that she is least able to bear is moral confusion.’ Lindsay, teaching a philosophy seminar on whether animals have souls, is tormented by the idea of perfection. Do dog owners live vicariously through their animals? Can dogs be superior beings because breeding can lead to their perfectibility? Is he the type of man to whistle for his children when their playtime is over?

The ease with which Lohrey evokes these characters and situations highlights the elegance of her writing. It is not just the dialogue she creates for them, but the way she reveals their thoughts. She is disturbingly accurate in her understanding of male psychology. As Kirsten and Lindsay eat at a restaurant, Lindsay acknowledges: ‘Uh-oh. He’s wandered again and she’s caught him out … “I asked you a question.” Had she? What was it? “I’m sorry,” he says. “It’s this headache. And probably low blood sugar.” He rubs his temples, for effect.’

Just in case you are reluctant, like Lindsay, to descend from your head, Lohrey provides a dramatic break in the narrative two-thirds of the way through the novel. It is jolting, but Lohrey’s seamless writing quickly refocuses the reader’s imagination. Sonia, a shadowy figure, an individual almost as unformed as the potential person of a foetus, reflects: ‘It seemed that all around me people fell in love, effortlessly and with abandon, but in my case I knew that it would have to be willed.’

Post-publication, media discussions have given the impression that Lohrey has written a dissertation or an advice manual. The Philosopher’s Doll is neither of these. It is a magnificent novel that explores options rather than preaching. If you happen to share Kirsten’s position, do not be afraid to read this story; it will strengthen your confidence that you can listen to your instincts, and that your own happiness is important.

The ticking of the biological clock can agitate the reader as well as the breeder. Discerning readers of The Philosopher’s Doll will be glad that the experience enriches their appreciation of fine literature, and grateful that Lohrey, whose Camille’s Bread (1995) was both moving and technically superior, has defied modern trends among writers by improving the quality of her work.

Many novels display some of the characteristics that encourage readability: consistency of theme, soundness of structure, steadiness of pace, depth of characterisation, and elegance of style. In The Philosopher’s Doll, Lohrey demonstrates that she has consummate control of all of these skills. Lohrey’s beautifully balanced, expertly crafted novel is a treat for head and for heart.

Comments powered by CComment