- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first book of fiction is a little sub-genre with a number of readily recognisable features. It’s loosely structured and tends to be episodic, without much of a plot. It’s at least partly about love and sex, preferably of an obsessive or otherwise significant kind. And it’s at least partly autobiographical. If it’s already a bad book, then these things do tend to make it worse, but if it isn’t, then they don’t necessarily detract; it’s not a value judgement, just an observation.

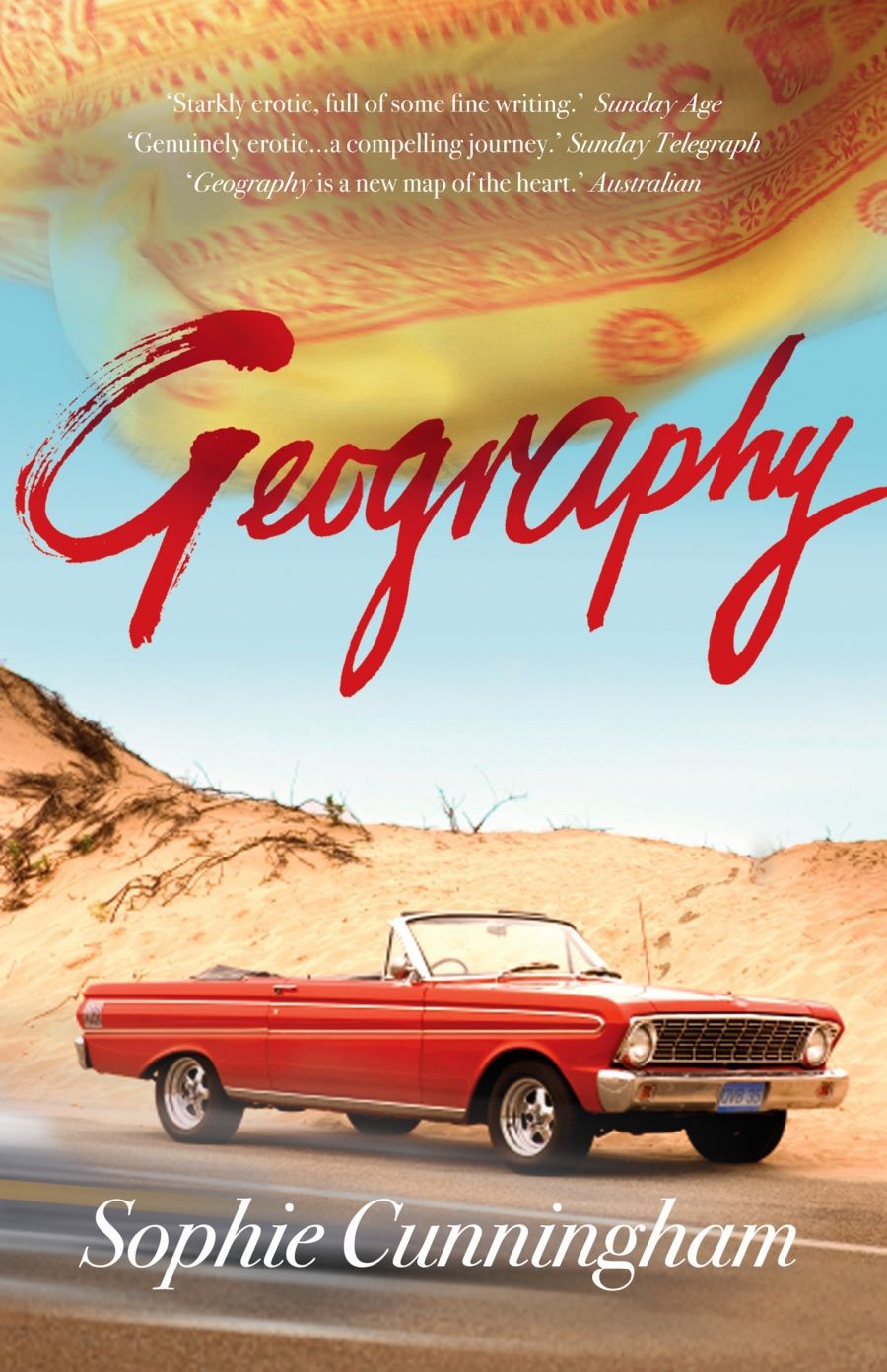

- Book 1 Title: Geography

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $25 pb, 208 pp

Sophie Cunningham worked for some years in Australian publishing and has lately made a living as a freelance writer and television columnist; she is a great deal more knowledgeable than most first-time authors about the necessary skills and the likely pitfalls of fiction-writing, and might have been expected to profit from her experience by somehow skipping over that First Book stage. But Geography still bears its identifying marks.

The narrator–heroine is recovering from an affair with an older man, an affair that has been dominating her life one way and another for the best part of a decade. Like many contemporary affairs, it has been conducted mostly at a long distance and mostly electronically. Her name is Catherine, which one supposes many readers will still associate with the great English classic novel of obsessive passion and romantic love. But Catherine Earnshaw of Wuthering Heights comes to an early, sticky end. Cunningham’s Catherine is a modern girl and a valiant fighter against her own weaknesses; her struggles to escape from the sad mess of her own passion make up the main subject matter of the novel. This could easily be awful, but it isn’t; Cunningham’s writing is too good and her heroine too likeable. And the book’s best feature is one that doesn’t seem at first blush to have a lot to do with Lurve; it’s also about the beauties, the mysteries, and the grim realities of India:

In Mysore I bought tikka powder for my forehead and I still have the little plastic containers of colour: China red, vivid blues and greens, intense orange. Piles of flowers were placed as offerings at makeshift Hindu temples on every street corner. One day, on one of those same street corners, I stepped over the dead body of a baby girl who was laid out on a rug, a box beside her tiny corpse into which people were invited to throw coins.

Cunningham uses travel as an analogy for sex, and geography as a loose and stretchy metaphor for love: ‘I was in love with my geography teacher when I was at high school.’ Catherine is manifestly a girl who gets what she wants, at least in the short term, and the former geography teacher is also a former lover, testament to ‘the first time I confused a continent with a man. The first time I loaded the fragility of love with the weight of a nation.’ But further on in the story, Catherine takes this parallel further back in life, to her discovery of sex: ‘What began as an opening to pleasure became a way of closing down. Sex became like the dreams of travel, something so sweet, so powerful, that I forgot the point of them. Both took me out of myself until it seemed there was no getting back.’

While the geography teacher is represented as rather sweet and wacky, Michael – the object of obsession – is an ageing expatriate academic in Los Angeles, and the reader can’t help thinking it’s a regression. If Catherine’s behaviour is pathological, Michael’s is not only equally so, but gratuitously cruel as well; what’s more, he comes across as a humourless and narcissistic prat, which I suspect may not have been Cunningham’s intention. Michael’s character and the effect he has is what this book is really about, but it also has some of the other dimensions one expects from good fiction. The geography parallel is neither original nor subtle, but it does work on the literal level as well as on deeper ones, and some of the best writing in the book is about India.

The loyalty of her friends through even her most irrational behaviour in the grip of her obsession would be harder to believe if Catherine presented as a less lovable narrator, but her humour and her flashes of self-knowledge keep her mates onside, and will have the same effect on at least some of her readers. Telling her story to her new friend Ruby, she asks: ‘Do you ever feel that you’ve been beaten by something that other people think is quite trivial? And then you hate yourself twice over: for being defeated, and for the cause being so ... nothing ... compared to what most people deal with in their lives?’

The best-managed thing about this novel is its chronology; Cunningham moves elegantly and effortlessly back and forth across several decades’ worth of narrative and links up various causes and effects in Catherine’s life. The Michael narrative is framed as a story being told to a new friend in an exotic place; the act of storytelling itself is figured as an informal but successful analysis, complete (if this isn’t giving too much away) with transference.

As will by now be clear, it’s not a very complex book. But it’s distinguished by three things: the way its narrator remains endearing, no matter how mad her behaviour; its passion for India; and, finally, its excellent writing about sex, which is erotic without being contrived, serious without being solemn, and direct without tipping over into pornography. Readers who have already read and liked the section of this book that appeared in Peter Craven’s Best Australian Stories 2003 are unlikely to be disappointed by the rest of it. There’s even a happy ending.

Comments powered by CComment