- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a species of Victorian mystery story that is as pure an expression of nineteenth-century rationalism as you are likely to find. A strange event occurs which, at first glance, appears to admit no rational explanation; by the end of the story, it is revealed to have a logical explanation after all. Thus foolish superstition is banished by the pure light of reason. But there is another side to late-Victorian fiction of the unexpected, represented by Henry James’s ghost tale The Turn of the Screw (1898): a darker, slipperier, and far more unsettling narrative in which the supernatural elements are never satisfactorily explained and are charged with menacing psychological overtones.

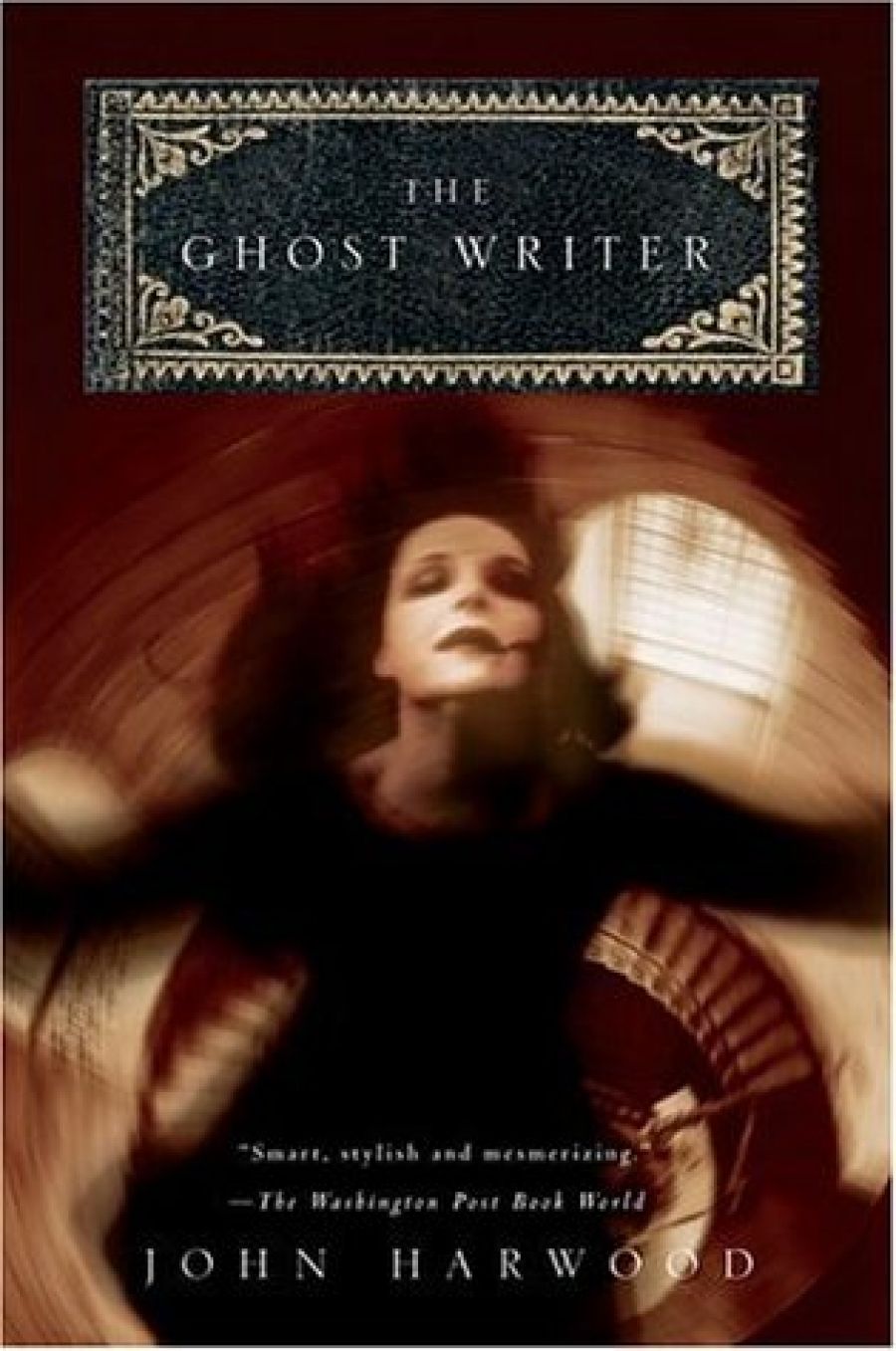

- Book 1 Title: The Ghost Writer

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $32.95 pb, 347 pp

John Harwood’s The Ghost Writer, although it is set in the twentieth century, is on one level yet another example of a contemporary novel that seeks to overleap the more aesthetically troublesome aspects of that century to commune with the literature of the nineteenth. Much of its dramatic tension is created by the conflict between the narrator’s sense of rationality and the apparently unaccountable nature of the evidence he uncovers. The raw materials of the plot – orphaned children, cursed legacies, portraits, ghosts, family secrets, found texts – have a familiar, deliberately anachronistic feel, and the novel buzzes with Victorian references, particularly to Henry James. Both The Turn of the Screw and The Sacred Fount (1901) are openly alluded to, and the narrator’s English penfriend is called Alice Jessell, a name that combines Miss Jessel from The Turn of the Screw with James’s luckless sister Alice, who was also a published writer, but who suffered from delusions, was bedridden for much of her adult life, and died young from breast cancer. (There’s another late-Victorian Alice who might be relevant, too.)

What makes The Ghost Writer superior to many recent attempts to recapture some of the spirit of nineteenth-century fiction is that it is not a homage but a reinterpretation. Rather than aping Victorian literature by presenting itself as a kind of generic throwback, it reworks some basic elements, treating them as a source of inspiration. Harwood’s neatest trick is to enlist the very familiarity of the novel’s motifs into the service of its uncanny atmosphere. The multilayered narrative is based around a mirroring that occurs between several texts, including some well-realised imitations of old-fashioned ghost stories. The consequence of this pastiche is an interaction – a dialogue – between the book’s various styles. It is a technique used to great effect to create a vague sense of unease as the narrator, Gerard Freeman, is sent in pursuit of a solution to a mystery that remains tantalisingly out of reach.

The Ghost Writer has the kind of suspense-driven plot that it would be difficult, not to mention indiscreet, to summarise in any detail, but its premise is that Gerard stumbles across a number of tales written by his late grandmother Viola Hatherley. As he reads them, he comes to realise that the stories possess a prophetic power. His grandmother’s fiction seemingly has the capacity to shape reality; stories written decades earlier anticipate later events and imply a dark secret in his family’s history. There is evidence that even Viola was spooked. ‘Sheer coincidence,’ she writes in one of her letters, attempting to explain away her work’s prescience; ‘literature is full of orphaned girls brought up by relatives – but there was something unheimlich about it’.

Harwood ably exploits the eeriness of this interplay between past and present. Switching between Gerard’s narration, his correspondence with his ‘invisible lover’ Alice, and Viola’s stories, the novel becomes an echo chamber in which Gerard finds it increasingly difficult to determine where fiction ends and reality begins. Each revelation raises new questions. It is unclear to what extent the connections he uncovers are coincidental, if he is being manipulated, or how much of his understanding is a product of his imagination. In this sense, The Ghost Writer can be read as a book about the inherently fraught business of interpretation. At the same time, however, it is also a novel with a strong sense of dramatic purpose and one that is written with enough skill to ensure that its momentum rarely flags.

If there is a criticism to be made of this unusually accomplished début, it is the back-handed compliment that it ultimately leans a little too heavily on its technical sophistication to the detriment of some of its interesting psychological undercurrents. One of the implications of the title is an acknowledgment of the invisible hand of the author, quietly going about the business of solving an ingenious problem of his own devising. But what makes a story such as The Turn of the Screw so disturbing is the way in which its central meaning remains unarticulated and to some extent unknown. The Ghost Writer offers up a conclusion that is cleverly wrought, but also tidy enough to draw attention to the mechanics of the plot. In other words, it does err on the side of a conventional mystery story. This is a quibble, really. John Harwood, who is the son of the late Gwen Harwood, has had a long career as a poet and critic leading up to The Ghost Writer, and it shows. First novels don’t come much more stylish than this one.

Comments powered by CComment