- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1927 the London firm Chatto & Windus published a book titled A Chinaman’s Opinion of Us and of His Own People. Supposedly the translated letters of a young Chinese man, Hwuy-Ung, sent home during his years spent in Melbourne, the writing suggested itself to its European and Australian readership as a delightful take on their society as witnessed by an innocent outsider; an enchanting, amusing and unwittingly insightful journal of a sensitive and bewildered Oriental gentleman. Written by an Australian called Theodore John Tourrier, the book was eventually exposed as a hoax, a cheeky, vaudeville-style tease hamming up the image of the courteous and comical Chinaman.

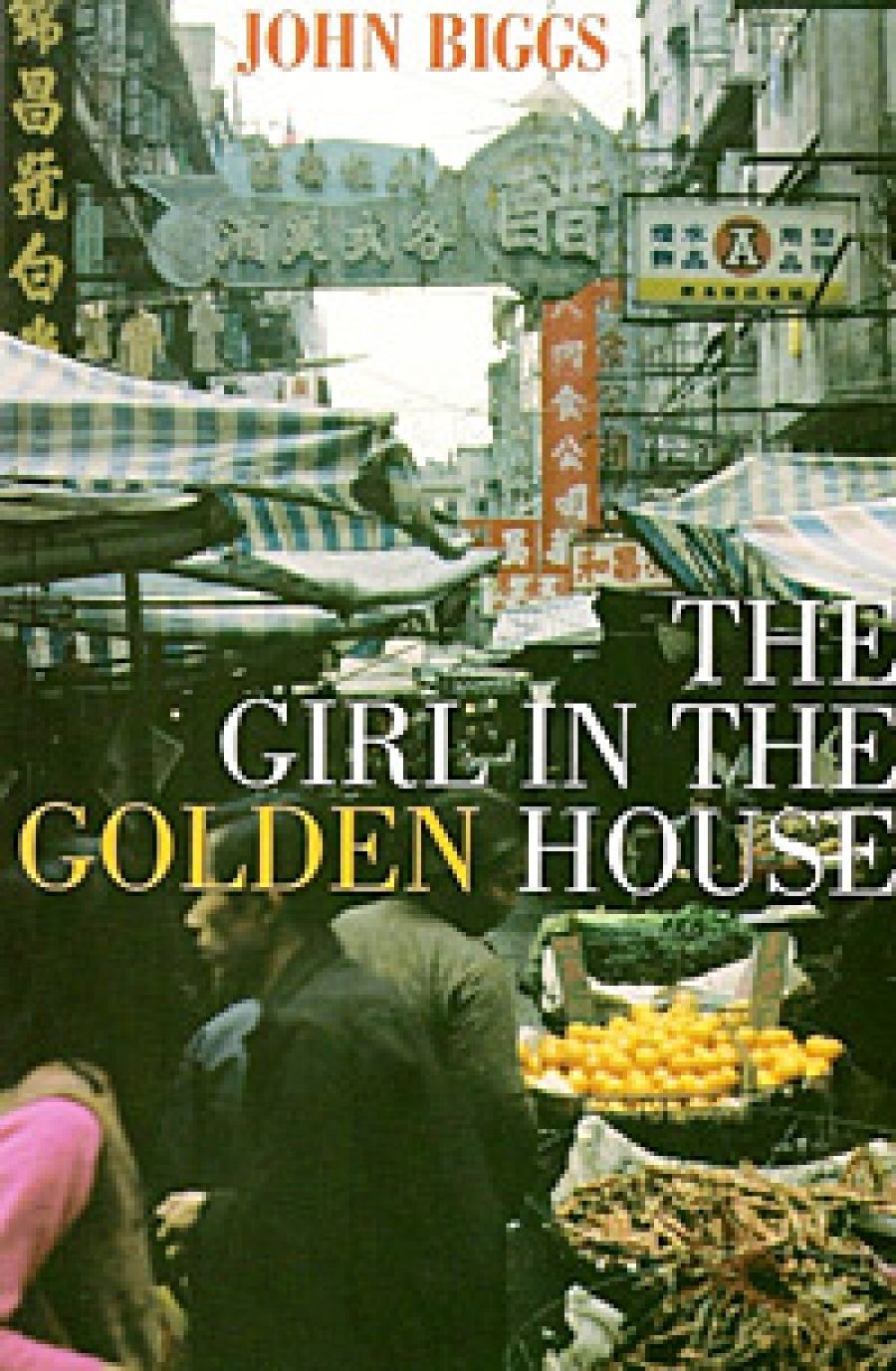

- Book 1 Title: The Girl in the Golden House

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $29.95 pb, 287 pp

Unfortunately, John Biggs, author of The Girl in the Golden House, does not exhibit this kind of awareness. He has written a book about a young Cantonese man in Hong Kong that departs little from his own estimations. As the biography printed on the cover attests, Biggs, after teaching English in Hong Kong for years, ‘now lives in Hobart writing full time about what he [feels] his life would have been like if he had been born in a different country, at a different time’. This, Biggs’s first novel, is the obvious result of such dreaming, the product of an older white man surmising what it would be like to be young and Chinese. Naïve in tone, familiar in its characterisation, the book performs a well-rehearsed act of ventriloquism, breathing life into its Cantonese characters with a romance of Biggs’s own.

Although presumably delivered in Cantonese, the writing remains entrenched in Western idioms, phrases such as ‘Bulls-eye!’, ‘You look as if you’ve seen a ghost’, ‘Just look at the god-awful mess those people are making’, ‘Agreed, Martin old chap’, and the odd slang reference to Shakespeare constructing both dialogue and narrative. Even more dis-comfitingly, characters occasionally spout Chinese proverbs: ‘I guess it depends on whether you tend to see your cup as half full or half empty,’ says Chris, the book’s main character, supposedly ‘add[ing] a touch of Eastern wisdom’. Chris discusses the way Chinese people see things as opposed to Westerners (‘Certainly, a Chinese in his position would see it that way, although I must say that this little Chinese … ’). For some inexplicable reason, his parents speak in broken English (‘A Chinese girl more better for you’).

At times, the book reads like Enid Blyton, with its young Cantonese characters Fanny, Billy, Emily, Flora, Lucy and Chris; its stable and conclusive cadences; the purity of its Chinese protagonists lit against the crudity of their Western counterparts; and a love story narrative designed along the struggle for good over evil, for virtue over sexual corruption. An example of the book’s sexual stereotypes, the heroine, Siu Ling, is the paragon of womanly perfection, a victim of others’ exploitation and of the tenacity of her own virtue. The only Cantonese character (apart from children and the elderly) who goes by a Chinese name, the virginal Siu Ling is introduced against the backdrop of the predatory British Felicity, a sexually experienced and vindictive ‘fox-demon’, whose curse haunts the novel. The characters’ adolescent love, moreover, is as cutesy as their Chineseness is innocent, Chris being ‘so proud’ of the way ‘Siu Ling changes inside our tent, and emerges a minute later in a frilly little, bright-red bikini with black splodges’.

Oddly, it is only Tourrier’s mischief that in any way redeems A Chinaman’s Opinion of Us and of His Own People, the fact of his own self-awareness, his knowledge of the fraud in the letters’ production the only thing to distinguish them from any other kitsch simulation of the time. In revealing the trickery of his literary techniques, Tourrier exposed what had been accepted as the naïveté of his exotic Hwuy-Ung to be that of his own readers, thus endowing the publication with a special intelligence and lesson. The Girl in the Golden House, however, remains stuck behind its author’s blind spot – evocative of Western fantasies of Hong Kong and its people, but offering little more illumination than this.

Comments powered by CComment