What distinguishes graphic novels (aka ‘big fat comic books’) from other books is how completely the page registers movements of the maker’s hand. Before we begin the business of reading, we look, and what we see is not margin-to-margin Helvetica or Times New Roman: it’s the mark of the makers, be it Alison Bechdel or Kristen Radtke or Mandy Ord. We might even think of the making of comic books as being closer to letter writing than novel writing. Accustoming ourselves to the style of a particular graphic novelist (‘Aha! That’s how Bechdel depicts euphoria!’) is a large part of the pleasure of reading comics – the business of aligning one’s own visual point of view with the maker’s. Perhaps this is why autobiographical works have been such a vital force behind the rebirth of comic books as ‘graphic novels’.

Alison Bechdel (‘rhymes with rectal’, as she informed us at a 2014 Wheeler Centre event) is the global superstar of autobiographical graphic novels, and her star has only taken on more sparkle with the improbable adaptation of her 2006 book Fun Home (closeted gay father suicides! literary references abound!) into a musical that took Broadway by storm, was staged in Sydney (ABR reviewed it in June 2021), and, Covid fingers crossed, will come to Melbourne in 2022.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel

Jonathan Cape, $35 hb, 240 pp

Fun Home, the graphic novel, presented the torrid world of Alison’s childhood home, crafted and honed into ‘a family tragicomic’, as the calling card on the cover proclaims. Fun Home joined Art Spiegelman’s The Complete Maus (1991) and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000) at the centre of the graphic novel canon. All three use autobiography to dissect trauma: familial, social, historical. Bechdel’s follow-up, Are You My Mother? (2012), explored her relationship with her mother and referenced psychoanalytic theory, in particular the work of child psychologist Donald Winnicott. It was a dense, exhausting slog of a comic book. But in this year’s The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel deploys her delicately droll lines, written and drawn, to construct a gentler, funnier self-portrait amid her usual storm of self-criticism and sardonic wit. She asks a question at the beginning of the book: just what is it that we are seeking in the agonistic rage for ‘fitness’? She spends the book running, stretching, cycling, telling, and showing us that it’s not the body beautiful, but the mind set free.

Bechdel’s art features her trademark crisp nib and ink work. Here, though, her fine lines are not highlighted by a sombre ‘spot’ colour, as per her previous two books, but are illuminated in full watercolour by her wife, Holly Rae Taylor. There is an excellent panel late in the piece that jokingly depicts the pair of them as medieval tonsured monks sitting opposite one another in their twenty-first-century scriptorium, in pandemic-imposed, drawing-board solitude, working away at the pages of this book. Excitingly, art-wise, with each chapter break Bechdel’s usually finely controlled nib work loosens into wide Zen brush lines. She’s discovering something new, and she’s taking us with her.

Seek You by Kristen Radtke

Pantheon Books, US$30 hb, 352 pp

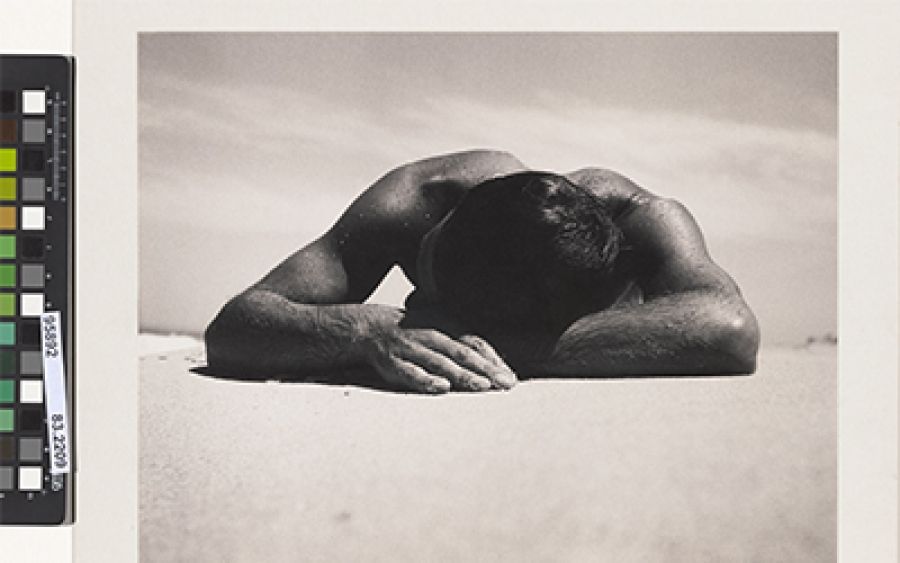

Kristen Radtke’s Seek You: A journey through American loneliness seizes on the idea that we are in the depths of a loneliness epidemic and expands this into a book-length visual essay. Because a comics page takes much less time to read than a page of text, a graphic novel running to this length will take you the same time to read as a magazine-length essay. Radtke, art director and deputy publisher of The Believer magazine, was brought up in the buttoned-down Midwest, then as a young adult lived in the fever-dream cities of New York and Las Vegas, and she examines how these social experiences shaped her image of loneliness. She discusses the research on socialisation and the effects of social isolation, including Robert D. Putnam’s Bowling Alone (2000) and, more scathingly, psychologist Harry Harlow’s cruel experiments on rhesus monkeys.

As with Bechdel’s and Ord’s most recent books, the maker’s life partner features in the narrative. In Radtke’s case, her husband’s long-ago purchase of a gun continues to gnaw at her. Radtke creates her illustrations from photo reference and her artwork bears an unfortunate consequence of this approach. The images are accurate but stilted, and in a book about loneliness, their curiously affectless, detached nature certainly makes this a lonelier text. ‘Loneliness lives in the gap,’ says Radkte, ‘between the relationships you have and the relationships you want.’ What we want is more emotional connection with the images in a visual text, in order for that text to have greater resonance.

When One Person Dies the Whole World Is Over by Mandy Ord

Brow Books, $24.99 pb, 376 pp

The autobiographical push is also important in Australian comics, and Mandy Ord is one of the great local exponents. Her one-eyed ‘Mandy’ avatar moves through a world of two-eyed humans, and this anatomical abnormality is an elegant analogue for our experience of sight: it doesn’t feel like we have two eyes, even though we can see that everyone else does. It’s also an instant identifier of her main character, as iconic as Charlie Brown’s zigzag shirt. Ord has been using this avatar-figure to tell autobiographical stories for decades, but even within such a long practice, this book is a staggering high point. When One Person Dies the Whole World Is Over, longlisted for the Stella Prize in 2020, features on every page a four-panel account of Mandy’s day, one for each day of a year. We accompany Mandy at her two jobs, walking the dog, making dinner, gardening, watching The Walking Dead with her partner. The book is intimate: we accompany Mandy on her daily commutes, we see the bird on the fence. It’s epic: we are invited into the vast emotions that lurk within everyday life. It’s also microscopic in its recording of those corner-of-the-eye moments that otherwise get lost in the swirl of events.

Ord’s facility with the ink brush – even the lettering is made with the brush – is such that, as in Bechdel, we feel deeply, bodily, and boldly connected to the tidal flow of the life on show. The fluid, monochrome world that Ord conjures, even when the life she is documenting – her own – is overwhelming, is an eloquent argument against loneliness. Autobiography is where the energy is in comics at the moment. By the strength of their hand-drawn work, Bechdel and Ord sweep us into their worlds, inviting insight about how to live with others, and with ourselves.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)