- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Take a step forward’

- Article Subtitle: An eloquent Holocaust story

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

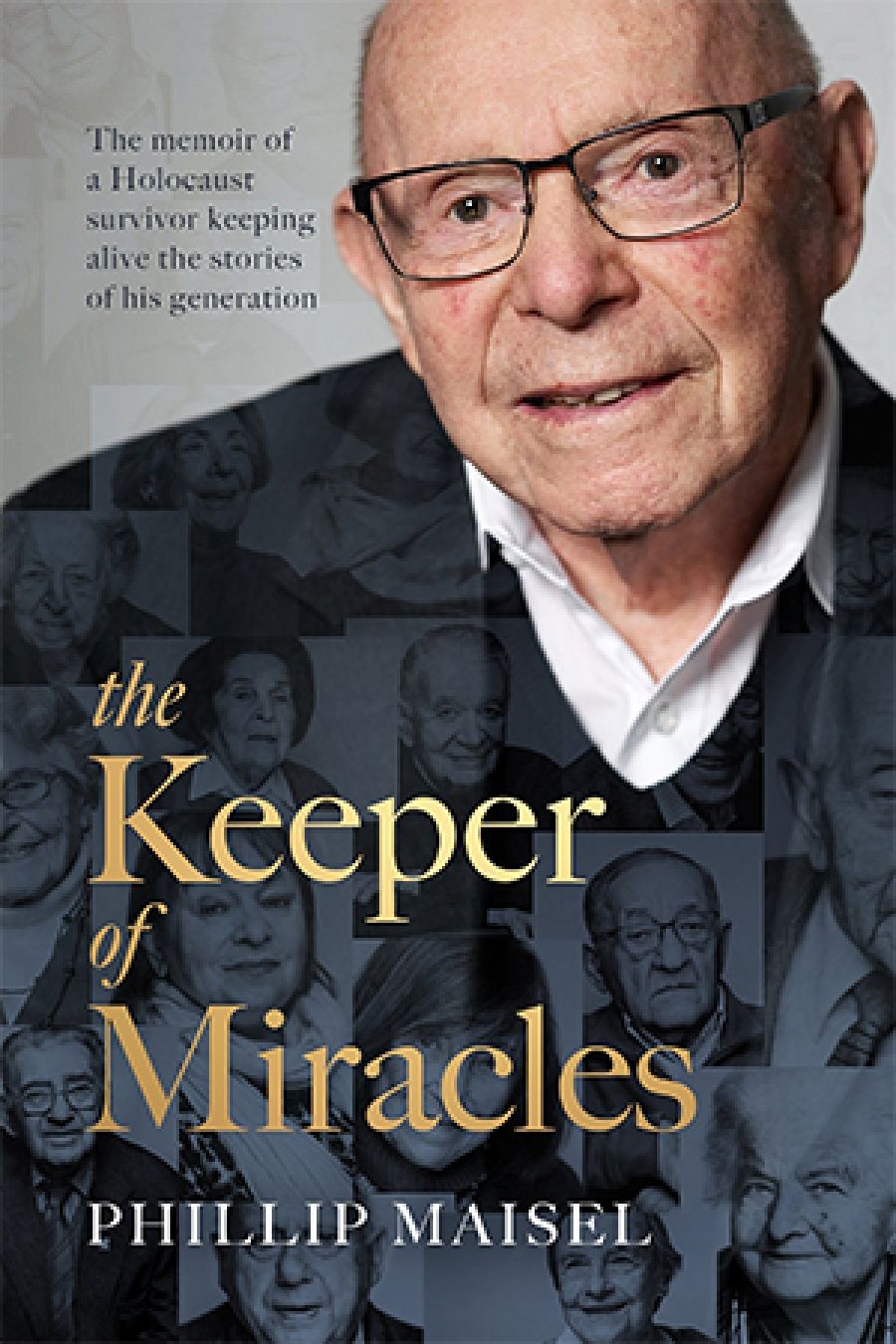

Not many people create an archive. For almost thirty years, Phillip Maisel led the testimonies project at Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC). Maisel’s memoir is his story of surviving the Holocaust and becoming ‘the keeper of miracles’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alistair Thomson reviews 'The Keeper of Miracles' by Phillip Maisel

- Book 1 Title: The Keeper of Miracles

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $32.99 hb, 214 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9QQV3

Maisel also recalls moments of kindness and care: the Lithuanian soldier who does not sound the alarm when he discovers Maisel and his family outside the Vilna ghetto; the German foreman who knows Maisel is desperately weak with typhoid and likely to be shot but saves his life by pretending he is at work; the Dutch, French, and Belgian gentiles on a death march in 1945 who respond to the SS command, ‘All Jews, take a step forward’, by stepping forward themselves until the furious SS ‘finally gave up and rode off’. Maisel explains that these ‘miracles’ of survival were not simply luck or divine providence: they were ‘humanity in its purest form … Every “miracle” I have experienced boils down to one thing – a human being making a decision to reject hatred and fear, reaching out to help another, to save a life.’ On an especially bleak day, as five labour-camp friends shared their daily ration of three potatoes, one man lamented, ‘None of us are going to survive this.’ Maisel responded, ‘If any of us make it, we will tell the world what the Germans did. We will hold them responsible for all of this.’ They promised then shook on it. ‘We would not be forgotten.’

Maisel acknowledges that people usually survived the Holocaust because they could be useful to the Nazi war effort. He was saved when a friend found him a job in a garage. Knowing nothing of cars, Maisel’s determination to learn the skills of a car mechanic, in a mobile garage that fixed German trucks, would save his life many times over. After the war, Maisel found work in the same garage, repairing Allied rather than German vehicles. When the garage was taken over by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, Maisel’s proficiency in several languages led to a job interviewing refugees. He learnt the skill of interviewing, how to spot dishonesty but also how to recognise trauma and ‘give people space to speak’.

In 1949, Maisel and his sister joined their uncle in Melbourne. ‘I wanted to move as far away as possible, to the other side of the world.’ Here he would marry and share the joy of daughters and grandchildren who were living proof that Nazism had not triumphed. Like many migrant parents, he worked two jobs, night and day. His daughters saw him so rarely they took to writing him letters. He could not talk with his family about his wartime experiences. How could they comprehend? With other survivors, ‘we could speak of nothing else’.

In retirement, Maisel volunteered at the Jewish Holocaust Centre, a museum and archive established by Melbourne’s survivor community in 1984. He joined the JHC’s ‘ad hoc’ oral history project, conducted his first video interview in 1992, and was soon running the project, interviewing almost every day and sitting in on interviews recorded by other volunteers to provide moral support and help survivors ‘keep track of dates and places’. Driven to honour his wartime promise ‘to tell the world’, Maisel also knew that six million deaths were almost impossible to comprehend. ‘However, it is possible to identify with one person, with one individual story.’

The Phillip Maisel Testimonies Project contains 1,700 life-history interviews about the Holocaust, the pre-war society of European Jewry, and settlement in Australia. Among the tens of thousands of Holocaust oral histories recorded around the world in recent decades, this Melbourne collection stands out in several ways, shaped by Maisel’s influence. Many recordings are in the mother tongue, ‘with an eloquence and accuracy that can otherwise escape them’ in English. Maisel and his narrators ‘shared a frame of reference’, about ‘hunger’, for example, that enabled deep listening and evocative remembering. Alert to the vagaries of memory and not wanting to give ammunition to Holocaust deniers, Maisel was prepared to gently challenge a story that did not seem right. ‘Are you sure it happened the way you are remembering it?’ Often the narrator would think again and offer more careful detail and more complex remembering.

Passing these stories on to the next generation will be, as Phillip Maisel concludes, ‘the greatest miracle of all’.

Comments powered by CComment