- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Diva

- Article Subtitle: A biography of Dame Nellie Melba

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

There were divas before Nellie Melba and, given that nowadays any young woman who can hold her career together for a few years while screeching into a microphone has the title bestowed on her, there have been many genuine and ersatz ones since. But Dame Nellie (1861–1931) remains the ne plus ultra, the gold standard of opera divas. Essential attributes include an instantly recognisable voice, an unshakeable faith in one’s ability, and position in the world, and an equally unshakeable determination that no rival will intrude upon one’s limelight. Nellie Mitchell showed these traits from an early age.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20copy.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Dame Nellie Melba, <em>c</em>.1907 (Rotary Photo/National Library of Australia/Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Dame Nellie Melba, c.1907 (Rotary Photo/National Library of Australia/Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Dickson reviews 'Nellie: The life and loves of Dame Nellie Melba' by Robert Wainwright

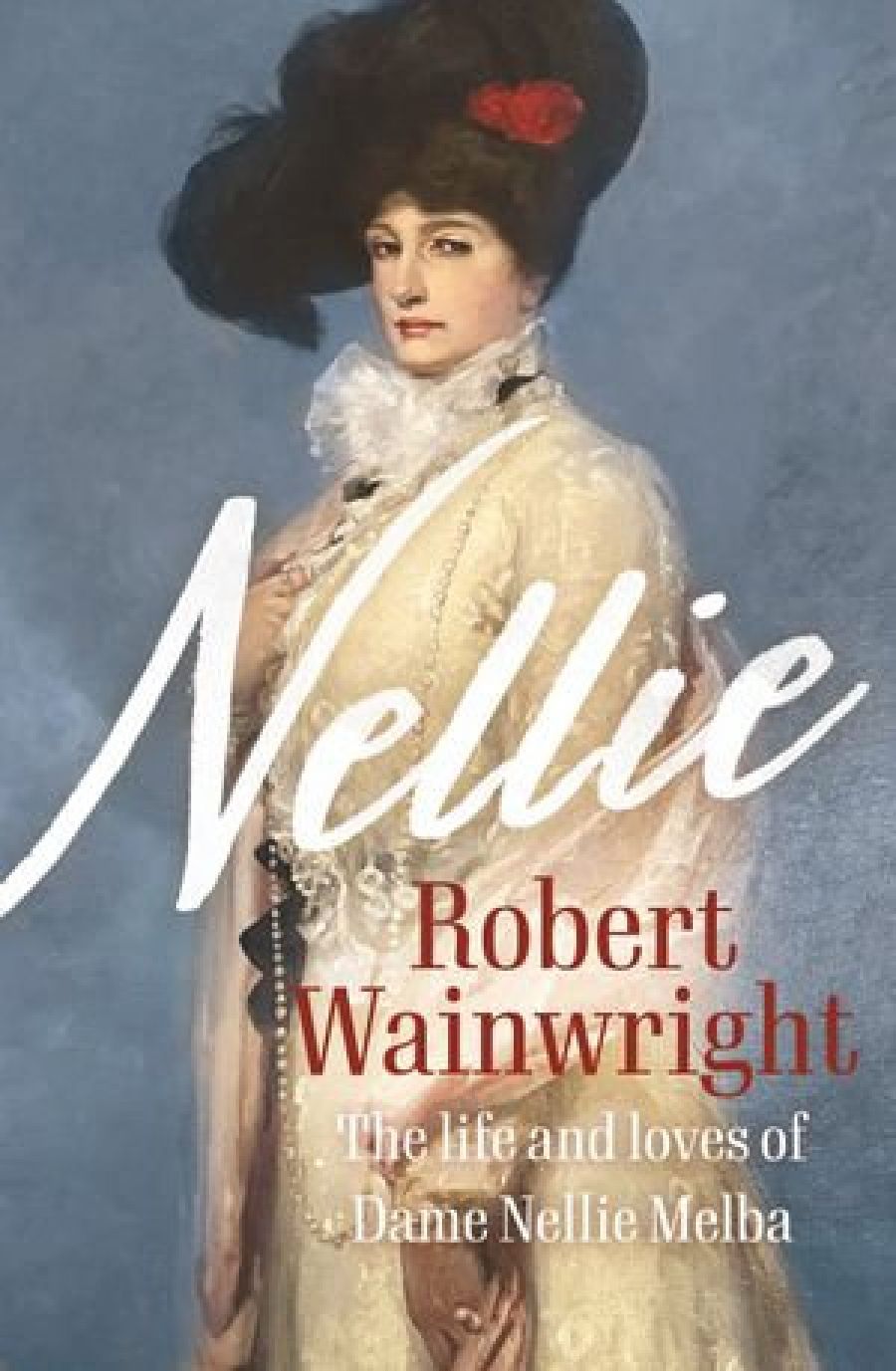

- Book 1 Title: Nellie

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and loves of Dame Nellie Melba

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 344 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2rMMG0

Born in Melbourne to a successful immigrant Scottish building contractor, David Mitchell, she fought against the convention that a middle-class woman could not sing professionally. In an effort to distract Nellie after her mother and younger sister died, her father took her to Mackay where he had an offer to build a sugar mill. There she met and married Charles Armstrong, the younger son of minor British aristocracy. This union proved to be a long running disaster but it produced a son, George.

Hastily abandoning North Queensland, Nellie, Charles, and the baby hitched a ride to London with her father. London proved unsympathetic, so she went to Paris where she was taken on by Mathilde Marchesi, one of the foremost vocal coaches of the day. The pair decided that Armstrong was not a suitable name for an opera star and rechristened her Melba.

There followed a successful début at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels and a less successful one at Covent Garden. Luckily for Melba, her Brussels performances had been witnessed by the English socialite Lady de Grey, whose husband was part of the syndicate that financed Covent Garden. Her Ladyship made sure Melba’s return on 15 June 1889 in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette was a social event. Melba rose to the occasion and from then until her farewell performance on 8 June 1926, she was the Garden’s reigning diva. Her subsequent career was a series of almost unbroken successes. She performed throughout Europe from Palermo to St Petersburg, and toured the United States. After sixteen years she returned to Australia for the first of many tours, two of which were as the head of a full opera company.

She was lucky in that her peak period coincided with the birth of the gramophone; she benefited from the promotional skills of the recording companies. This nexus between opera stars and record companies was mutually beneficial through the last century. One wonders if Maria Callas would have been quite as famous without the backing of EMI. At any rate, by the first decade of the twentieth century Melba was not merely the most famous Australian but also one of the best-known women in the world.

Lady de Grey introduced Melba to the raffish social set that surrounded the prince of Wales. and it was there that she met Philippe, duc d’Orléans, the Bourbon pretender to the French throne and without doubt the love of her life. Though the social mandates of the time meant their relationship could not last, they remained affectionate towards each other for the rest of their lives.

Given that, by popular assent, acting was not Melba’s greatest strength – it was said that when she wanted to convey emotion she raised an arm and when she wanted to convey deep emotion she raised both arms – her extraordinary power over her audience was due to the quality of her voice alone. The Scottish soprano Mary Garden, with whom Melba shared a wary respect, found Melba’s thespian attempts laughable but was in awe of her voice. Speaking of the high C with which Mimì ends the first act of La Bohème, she recalls: ‘the strangest and weirdest thing I have experienced in my life … The note came floating over the auditorium of Covent Garden; it left Melba’s throat, it left Melba’s body, it left everything and came over like a star and passed us in our box and went out into the infinite … My God how beautiful it was.’

There have been many biographies of Nellie Melba, including the wonderfully florid, partly fictional autobiography she co-wrote with Beverley Nichols, Melodies and Memories (1925). The subtitle of Robert Wainwright’s book, The life and loves of Dame Nellie Melba, leads one to suspect that this will be either a highly romanticised Mills & Boon version or a salacious trawl through her private life. In fact it is neither. Wainwright has decided to concentrate on the relationship between Melba and the duc d’Orléans, which he contrasts with the Armstrongs’ marriage. He leads us briskly through Melba’s early years and first successes, and once both Phillippe and Armstrong are out of the way, positively gallops through the rest of her life.

In contrasting the two men, Wainwright gives Melba’s husband no quarter. Armstrong was a brutal man and no angel, but Wainwright makes it look as though George was only too glad to leave him. In fact there was much affection between father and son. George took his wife to visit his father and actually managed to persuade Melba to let him stay at her Australian house, Coombe Cottage. None of this is mentioned in the book.

Wainwright’s knowledge of opera and its history seems less than profound for someone writing about an opera diva. He mistakenly demotes the French soprano Emma Calvé, the leading Carmen of her day, to the secondary role of Micaëla. He describes Brünnhilde as a ‘mythological warrior queen’, which would have surprised Wagner and irritated the goddess Fricka, to whom her stepdaughter was just a very naughty girl. But the main problem is that the relationship between the prince and the diva isn’t strong enough to carry the weight of the book. While Melba’s life is fascinating, the aimless wanderings of a man who spent his life either hunting or ineptly attempting to revive the French monarchy isn’t. The duke’s legacy to the French nation was a collection of stuffed animals he had slaughtered.

For those with an interest in French royalty and taxidermy, this may be the book for you, but for those truly interested in Nellie Melba, Thérèse Radic’s Melba: The voice of Australia (1986) or Ann Blainey’s I Am Melba (2008) are the books to read.

Comments powered by CComment