- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Joyful latitude of risk

- Article Subtitle: Life lessons from Australia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 2016, New York Times correspondent Damien Cave moved his young family to Sydney to establish a foreign bureau for the newspaper. As he writes in his new book, Into the Rip, the experience has been transformational, teaching him among other things that ‘None of us is trapped within the nation we come from or the values we picked up along the way’. Despite political and economic alliances, Australia and the United States are not clones of each other, and in many ways Australia proves ‘the healthier model’ for a society. Cave learned these life lessons, he reports, through ‘the combination of fear, nature and community spirit’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Mason reviews 'Into the Rip: How the Australian way of risk made my family stronger, happier … and less American' by Damien Cave

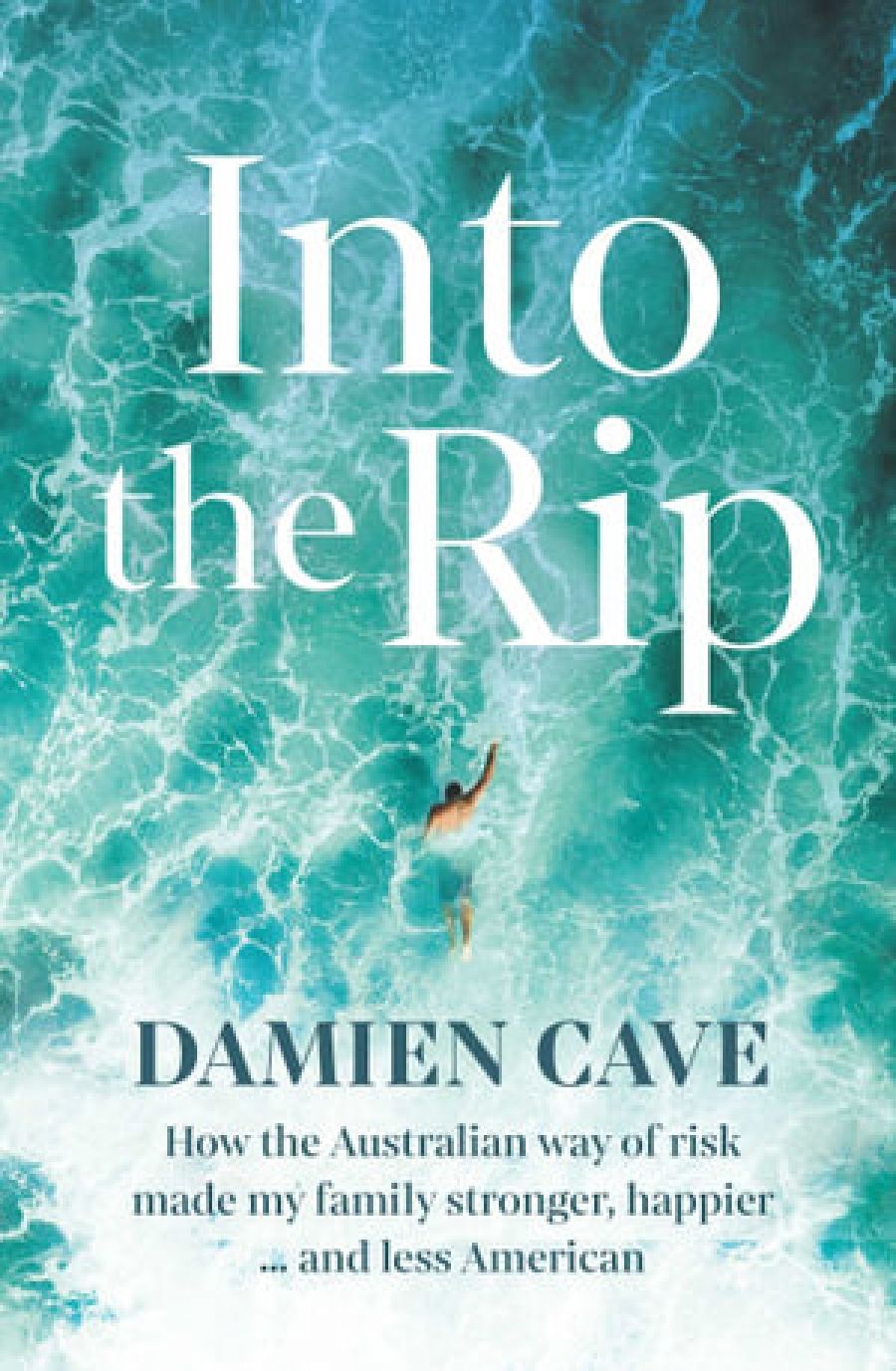

- Book 1 Title: Into the Rip

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the Australian way of risk made my family stronger, happier … and less American

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 311 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/oe00AY

Cave’s book is part memoir, part reportage of social trends, part meditation on the meaning of risk. ‘In so much of Western culture,’ he writes, ‘we have drifted into physical comfort and psychological insecurity. We have prioritized attention, feelings and speech, not conduct. Our phones and algorithms promote connection but serve up isolation. Every day, we choose convenience over uncertainty, overvaluing pleasure and ignoring what hardship has to teach.’

To those for whom hardship, economic or otherwise, is a given, Cave’s narrative might seem a precious luxury, but his book serves as a useful reminder of Australia’s blessings and America’s troubles. We must all learn to live with uncertainty, and there is no better teacher of these lessons than nature, a fact modern societies too often deny. Cave relates his encounters with the sea, the surfing and lifesaving culture of Sydney’s beaches, where children and adults learn resilience, care for one another, and respect for forces they cannot control.

This cultivation of risk may seem strange to some readers. Cave and his wife, Diana (also a journalist), had taken risks before, reporting from Iraq in a particularly bloody year of warfare. He also ran the Times bureau in Mexico City, a place with its own dangers. Australia seems by comparison one of the safest places on earth, but Australian culture gently nudged him to face up to his Americanness, the blinkered egotism of a country that perpetuates myths of its own exceptionalism. He admits mistakes as a reporter, weaknesses as a father and husband, the way American individualism and careerism had made him a man he no longer wanted to be. Cave finds danger in his ignorance of the sea, which his family confronts by learning how to swim properly, to surf and practise lifesaving techniques. But he also finds it in horrors like the Christchurch shootings (perpetrated by a white Australian) and divergent responses to the pandemic, events that are harder to reconcile with one man’s personal growth. His children join Nippers, his wife risks new ventures in business and writing, and he steps far out of his comfort zone to go for Bronze in lifesaving. They mix with other people, learning from Australia’s more collective world view to overcome their fears.

Cave indicts societies that ‘let their children stay fragile by avoiding imperfection’. The values of self-esteem perpetuated in many US schools have reached ludicrous levels. ‘So many of the people we had encountered in Miami and in Brooklyn were both terrified of physical danger for their children and desperate to keep them perpetually happy and worthy of praise.’ American schools and universities are demonstrably more prone to grade inflation and the paternalistic coddling of students, trends that Cave traces to the psychological theories of figures like Nathaniel Branden, an ‘acolyte’ of Ayn Rand.

I am older than Cave, and remember a more resilient America. My family were mountaineers and sailors, affirming his point that nature is the best teacher, though at times a harsh one – my older brother died while mountain climbing. Still, I would never deny anyone the joyful latitude of risk. Cave grew up in a culture of alienation, every person for themselves, stressing career and individual accomplishment – the sort of American egocentricity that makes Australians roll their eyes. His story bends toward humility, revelation, and, ultimately, new life through activity and change.

Reporting on a wonderful immigrant named Zurbo who lives in Tasmania, Cave finds himself playing Aussie Rules – lightyears away from American football. ‘For the first time,’ he writes, ‘I fully understood a game I had only watched. I also saw how quickly nervousness and the pain of embarrassment could be transformed to improvement and fun, especially if there was someone to apprentice with.’ On a more disturbing level, the Christchurch attack forces him to confront the racism common in both the United States and Australia, the way both societies have been slow to recognise white male terrorism. ‘The attack’s aftermath had pushed me beyond the personal – it made me desperate to know why humans get risk wrong so often’. He could have said more about risks that Americans undergo due to gun violence and the denial of basic health care to many citizens, but his training as a journalist makes him reluctant to preach.

Cave could also have devoted more space to the importance of Aboriginal culture, its crucial lessons about a proper relation to nature and what other writers have called the soul of the continent. Set Into the Rip next to William Finnegan’s surfing memoir, Barbarian Days (2015), and you may find Cave’s book rarely breaks the bounds of good magazine journalism. The sea in Cave’s writing is less an awesome presence than a backdrop for a story of personal change. Yet his book touches on matters that I, too, as an American immigrant, find myself discussing with my Australian friends and family. Where has American society gone wrong, and can Australia avoid the danger of going the same way? He admits to being ‘unaware, and American’, and I know just what he means when he says, ‘We all need to get better at living’.

Comments powered by CComment