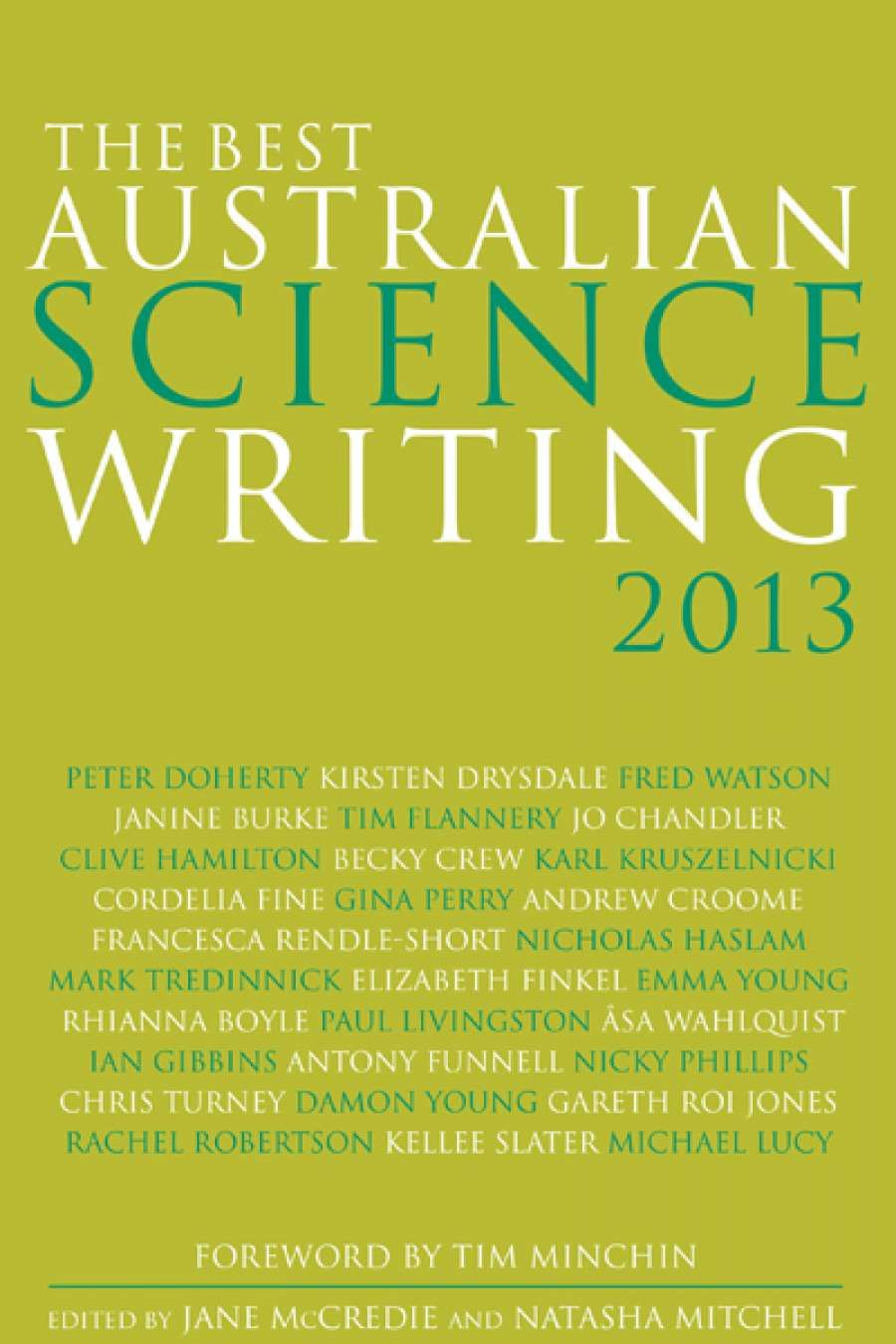

The end of the year tends to bring a small and exquisitely formed avalanche of Australian poetry, including Best Poems from Black Inc., Best Poetry from the University of Queensland Press, and the Newcastle Poetry Prize anthology. Sadly UQP gave up the ghost with its annual after 2009, but we have already had Australian Love Poems.

Black Inc. shows no signs of abandoning Best Poems: in fact it goes from strength to strength. It has had a run of editors lately who have made each iteration distinctive and differently weighted: Peter Rose, Robert Adamson, John Tranter, and now Lisa Gorton. Gorton, in her introduction, says that ‘Poetry, whose forms close in time, is a kind of writing that justifies the printed book – an artefact.’ That being the case, Best Poems has, since last year, had a vibrant new design that gives it a real identity as an annual object. On the shelf it is like that other regular pleasure, the Bedside Guardian, while inside the poems are beautifully set in a clear font on crisp creamy paper, and easily scanned and investigated.

This may seem superficial – surely the quality of the verse is the main thing? – but on opening Now You Shall Know, this year’s Newcastle anthology, it is clear why design matters. Faint type, on cheap paper with a grey tinge, almost defies the eye. The poetry just seems to be dumped on to the page. The contrast is shocking, and also of course unfair. Best Poems is produced by a commercial publisher which values design highly and is prepared to support it (and for the moment can afford to).

Now You Shall Know, on the other hand, is a prize anthology, published by the Hunter Writers Centre: all their money goes, rightly, to help writers, prize winners and otherwise. They simply don’t have the resources to produce typographic eye candy. But previous anthologies have been neutral, plain, and legible. Something seems to have gone amiss this year.

Best Poems has an élan, almost a swagger, that’s invigorating. There are newish faces here, but what’s perhaps most enjoyable is the way the seasoned players step up on the stand and show that they have their chops. John Kinsella, writing a poem while a bushfire approaches, does narrative and literary reference as only he can: ‘The breeze blows / from the east, but is ambivalent and could swing / about. There are no semantics in this. And Paul Auster / is right where William (the lumberman) Bronk was wrong: / the poem doesn’t happen in words, but “between seeing / the thing and making it into a word.”’

Jennifer Maiden offers up a riff on Frank O’Hara that plays with that ‘Forbes said to me and Tranter said’ mode that can be infuriating, but here is nostalgic and spirited. When a poet is enjoying herself as much as Maiden is here, and so surefootedly, there is hardly any more pleasure to be had from verse.

More soberingly, Clive James, in the face of death, abandons all his orotund autodidact armour to be heartbreakingly honest: ‘All of my life I put my labour first, / I made my mark, but left no time between / The things achieved, so, at my heedless worst, / With no life, there was nothing I could mean / But now I have slowed down. I breathe the air / As if there were not much more of it there.’

Best Poems regularly reminds you of those poets whom you have missed during the year, includingKen Bolton, Peter Bakowski, and π.O.Poets that one feels should be there this year are there – Kate Middleton, Toby Fitch, Michael Farrell, Pam Brown. However subjective this may be, it does give the ‘best poems’ aspect more weight.

Lisa Gorton (photograph by Sue Gordon-Brown)

Lisa Gorton (photograph by Sue Gordon-Brown)

Gorton takes the eloquent-shrug approach to the unanswerable question: ‘I hope the experience of reading this anthology will bring into question how far those abstractions – “best”, “Australian”, “2013” – exist in fact, and what end they serve as one thinks about the poems collected here.’ Although, sadly, Gorton cannot be in this anthology, her spirit is. The poems are set out alphabetically ‘to bring home the ritual and music of language, always more at play in poetry than in prose’.

Gorton looked for poems that seemed to her ‘surprising, generative, memorable’, and notes that after all the ‘transactions with possibility’ involved in writing a poem, some seem to ‘hold like an electric charge the trace of all those forfeited possibilities’. That is the feeling her anthology generates, and by and large it is a modern, metropolitan one, knowing and reflexive.

Now You Shall Know is utterly different. Putting aside its aesthetic failings (as one owes it to the poets to do), it still has a character all its own. For one thing, as a competition collection, it tends to longer poems, as the poets have stretched out toward the word limit, and also, one feels, toward the discovery of something rather than the display of something. It’s not always so, but this year the result is a biographical, familial, anti-rhapsody of a book. Parents die (as in the winning title poem by Jennifer Compton), partners lapse into dementia, lives go by, and are remembered, amid landscapes that refuse to be fully known. Tony Hancock dies in his hotel room in Sydney.

The anthology is remarkably unified, despite the competition not having a defined theme. The judges do say that ‘playfulness can have its own wisdom and can dance with profundity’, but if there is play here it is very muted. John Jenkins’s ‘Diary of a Missing Poem’ does its best to be picaresque and personifying, but rings flat, while John A. Scott’s poetic recasting of ‘Hancock’s Last Half Hour’ would need a lot more play and invention to justify its existence than is on offer.

However, in these poems there is always the land and family, and no time or need, in the end, for playful display. Mark Crittenden’s ‘Red Soil Elegies’ have all the intelligence required to dazzle, but instead meditate ideas into stillness. The poet knows his place, in every sense: ‘I have been out into the carbon-black night, / trusting my way from page / to wire barbs. Mostly I find myself // a little afraid, enlarged upon the landscape, / dwarfed at first light. / I travel less and less, preferring // local roads. Imagination’s international. / A vast itinerary awaits me at the desk. / At home, my family / are the earthwire and fire inside my words.’

This feeling has echoes throughout the collection. Third-prize winner Mark Tredinnick, as ever, fuses rural life with culture and intellect by sheer force of will, and defies the sadness such an enterprise inevitably brings with it. ‘Sorrow is happiness grown wise / after its own event,’ he says, from his tractor, with Debussy in the background.

Everything seems to be getting its eulogy in this anthology: a parent dying; a partner losing memory and life; family life and freedom from it. Even writing, in Dylan Gorman’s ‘Seasonal Work’, is given its threnody: ‘The nib of my fountain pen has developed a bias, an edge / worn down over the years by the pressure I bring to bear on paper. / This morning I am aware of the sound it makes.’

Now You Shall Know seems to exist far from the bright metropolis, in a quiet valley where there is still an unrecorded folk tradition, its songs full of death and strange companions. It tends towards a low drone, but the keening and the scrape of discordance, once heard, are there all the time, even back in the well-dressed world of Best Poems, and give that world a whole new tuning.