- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Natural History

- Custom Article Title: Peter Menkhorst reviews 'Lost Animals'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Quite lost

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Errol Fuller has played a key role in documenting historical extinctions of birds, notably the Great Auk and the Dodo. In the course of this work he has accumulated a fascinating collection of photographs of now extinct animals, many of them unique and not previously published.

- Book 1 Title: Lost Animals

- Book 1 Subtitle: Extinction and the Photographic Record

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $49.99 hb, 260 pp, 9781408172155

While displaying these photographs, Fuller detected a trend for photographs to elicit a stronger emotional response than paintings of the same species. We interpret photographs differently from paintings. Photographs seem more ‘real’, perhaps because they are produced instantaneously by a technological process that faithfully reproduces whatever is within the field of view according to the camera settings selected by the photographer. A painting, in contrast, is an artist’s interpretation, and therefore can seem somewhat removed from reality, even if the artistic style is photo-realism. We can test this phenomenon by referring to the appendix in Lost Animals where paintings of many of the species are presented. For me, the photographs are more compelling statements about the tragedy of extinction than are the paintings. This is what gives Fuller’s book its emotional punch; we see firsthand what we can never experience again, the living, breathing animal in situ shortly before the species was lost forever.

Thus was born the idea of presenting a selection of photographs of extinct animals with a brief text for each species giving details of the timing and causes of their decline, as well as how the photographs came to be taken and by whom. Twenty-eight species are featured, twenty-one birds and seven mammals. I found the predominance of birds disappointing – given the diversity of recently extinct species, did this small selection need to include two species of grebe and two woodpeckers? Species selection was, of course, dependent on the availability of suitable photographs, and also probably on the strength of the story associated with the species and the capturing of the images. Nevertheless, the exclusion of other animal classes does seem a lost opportunity. Where are the giant tortoises or gastric-brooding frogs, for example?

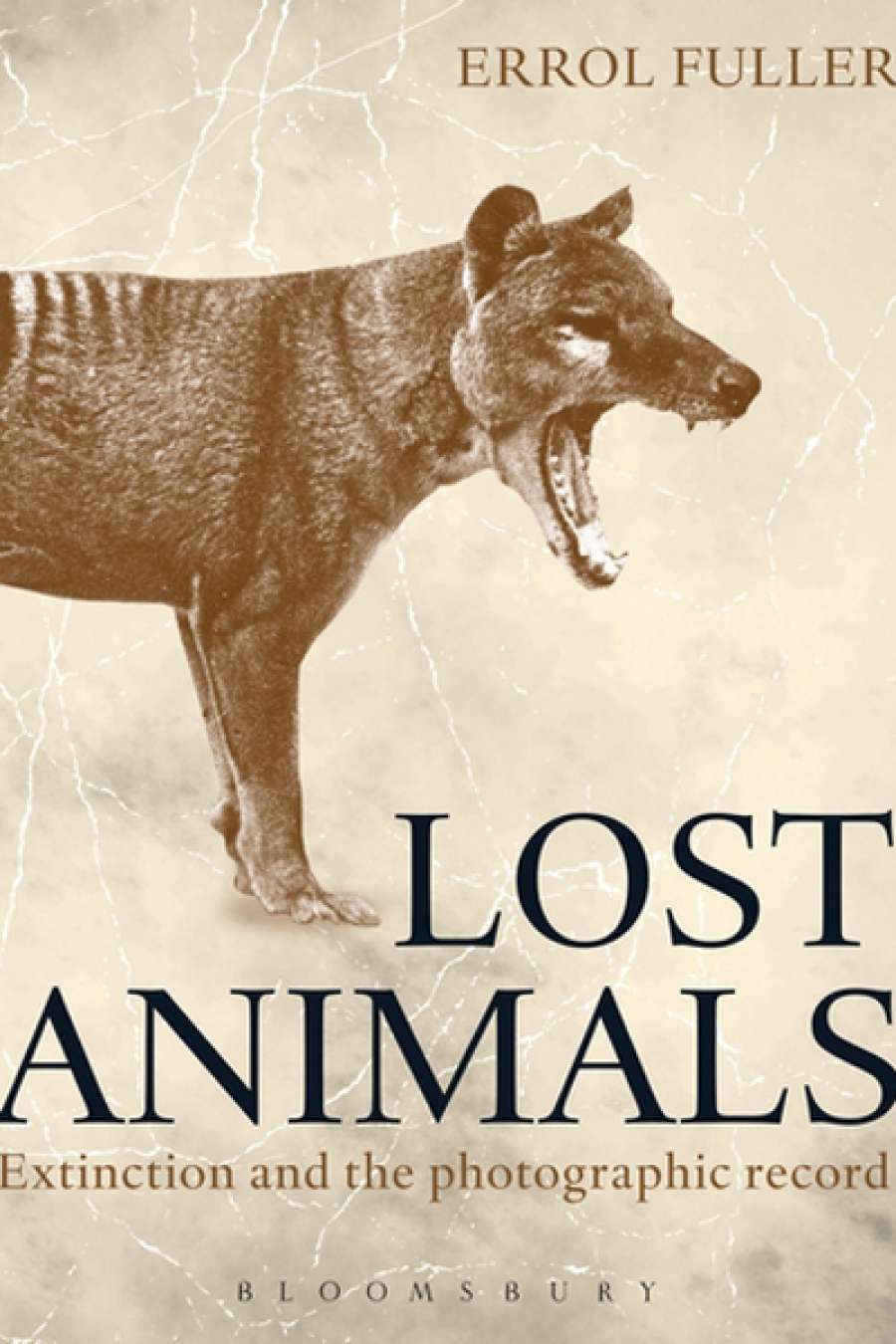

The last known Thylacine in a Hobart zoo (photograph by Benjamin Sheppard)

The last known Thylacine in a Hobart zoo (photograph by Benjamin Sheppard)

For a surprising proportion of the species treated here, the last known individuals were captive, making the photographs even more poignant. The maltreatment in inadequate zoo enclosures of the last living Thylacine, Quagga, and Bubul Hartbeest is manifest, their forlorn, listless expressions only adding to the tragedy of the imminent extinction of their species. Contrast this with the delightful insouciance of the Wake Island Rails and the nonchalance of a juvenile Ivory-billed Woodpecker perched happily on the hat of an ornithologist, unaware of the imminent fate of its species (but did we really need to see eleven similar photographs of the juvenile woodpecker?).

Some may wonder why we would care about extinct species and want to see old photographs of them? Extinction mostly happens to species lacking the capacity to adapt to changed conditions – they are losers, rightly passed by in the evolutionary race, of no value anymore, if ever, right? Anyway, extinction is a continuous, natural process – over the four-billion-year history of life on Earth there have been vastly more species become extinct than are alive today, so the loss of a few more is surely trivial.What does it matter if a small ground bird confined to a remote Pacific island disappears – hardly anybody ever saw it anyway.

In fact, as Fuller’s photographs beautifully illustrate, there is something particularly poignant about a species whose demise can be attributed to human influence. The subjects are ‘lost animals’ in more ways than one. Many of the photographs in this book show the last, forlorn individual of species that were brutally hunted, for example the last known Thylacine in a Hobart zoo, and Martha, the last of untold millions of Passenger Pigeons. Others were sacrificed for trivial reasons – arguably Australia’s most beautiful parrot, the Paradise Parrot of central Queensland, disappeared as its termite-mound nest sites were harvested by the local community to make en tout cas tennis courts.

The Paradise Parrot of central Queensland

The Paradise Parrot of central Queensland

(photograph by Cyrill H. H. Jerrard)

Many of the photographs are not technically remarkable, and some are quite amateurish, but care has been taken with their reproduction and they mostly succeed on artistic, emotional, and scientific levels. In many cases the murky images accurately reflect the challenges of wildlife photography – no airbrushed studio images here. Inexplicably, Fuller labours this point in his disappointingly brief and shallow introduction, unnecessarily apologising several times for the entirely unavoidable fact that most of the photographs pre-date Kodachrome slides and are black-and-white images.

The book succeeds on the level of preserving and presenting photographs of some extinct birds and mammals. Unfortunately, the narrative does not match the impact of the photographs. Fuller’s chatty style leads to inconsistencies in provision of vital information – dates and places are not always clear, and descriptions of the forces causing the declines are often simplistic. Presumably, there was a conscious decision to emphasise the human side of the story, but the short biographies of the photographers are frustratingly meagre.

Nevertheless the book was not intended to be a comprehensive documentation of these species. Rather, it is an emotional statement about what we have lost and continue to lose, with historic photographs as the centrepiece. The photographs are confronting and disturbing. They represent all that is wrong in our treatment of animals: exploitation, incarceration, habitat destruction leading to declining and fragmented populations that are steadily exterminated until none remains. This process of extinction usually plays out over decades and often goes unnoticed and unremarked. There is an urgent need to establish proper biodiversity monitoring programs so that we are forewarned and are able to ameliorate threats before more species are captured in the extinction vortex.

These photographs and their background stories should be front and centre in programs to improve attitudes towards our fellow life forms on planet Earth. Fuller is to be congratulated for bringing them so beautifully to our attention.

Comments powered by CComment