- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'In So Many Words'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ring the bell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I have often thought that a large part of achievement is just fronting up; having an idea and acting on it, however unlikely success might seem. What you need is a resolution (or the disposition) not to be discouraged by failure and to be pleasantly surprised by success. If it doesn’t work, you try something else. You make the most of any opportunity. You should also jettison a conventional sense of the social niceties. You’re going to Boston for your honeymoon. Hey, why not ask Noam Chomsky for an interview?

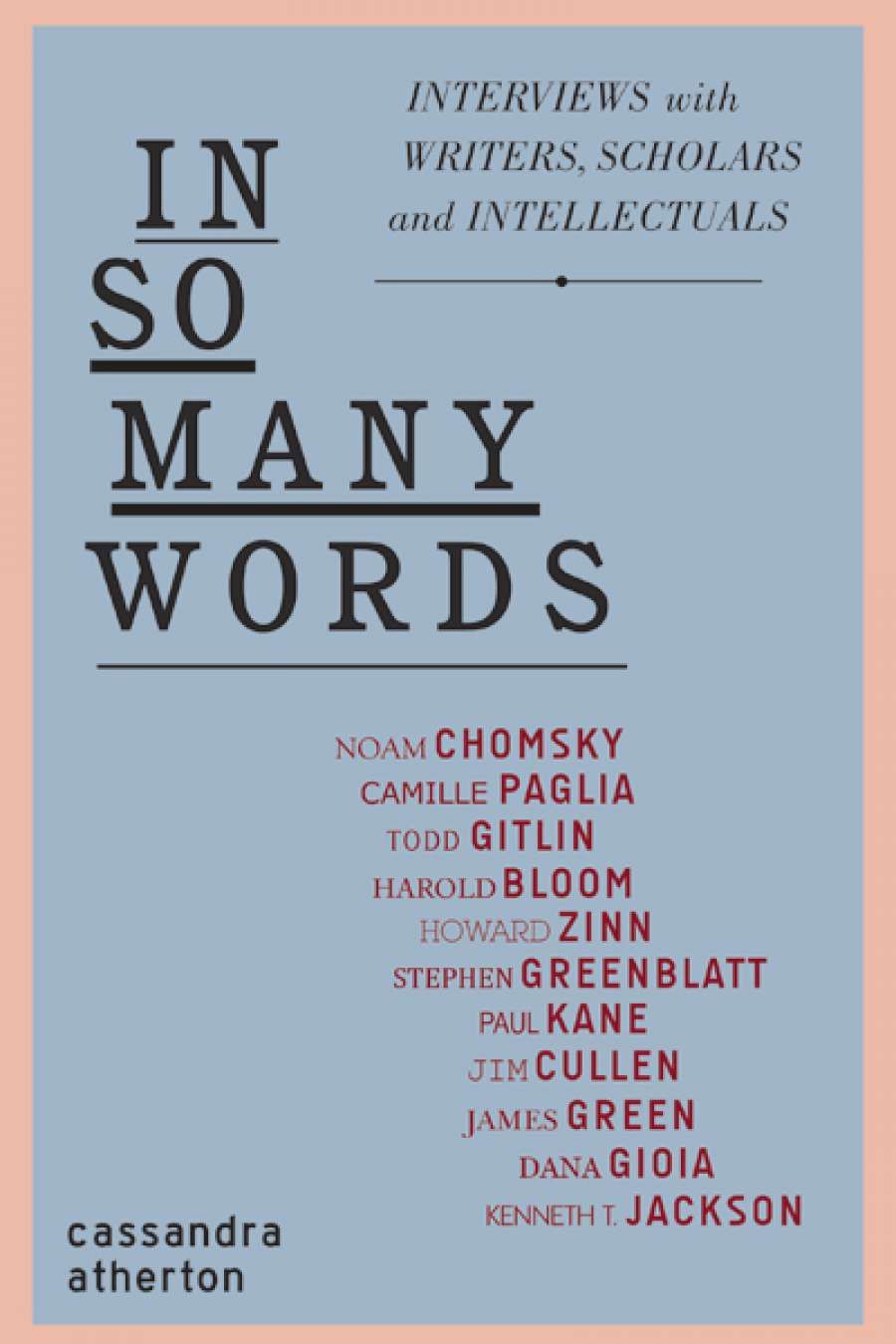

- Book 1 Title: In So Many Words

- Book 1 Subtitle: Interviews with Writers, Scholars and Intellectuals

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $29.95 pb, 151 pp, 9781925003062

Cassandra Atherton is not exactly nobody: she was a lecturer at the University of Melbourne when she began her project; she is now a senior lecturer at Deakin University – but still, a small fish in a large pond. Disarmingly, she explains in her introduction that her first bold request was prompted by the observation by one of her students that she ‘loved Harold Bloom’. Instead of indignantly denying the accusation, she courted applause by Photoshopping herself into a romantic pose with the grand old man of lit crit. Then, when she found herself travelling to the United States, she sent him an email.

This book is a strange blend of serious intellectual enquiry and star-struck breathlessness. Each interview is prefaced by an explanation of why and where (though, unfortunately, not always when) the interview took place. The ‘why’ tends to be full of superlatives and exclamation marks. Stephen Greenblatt is ‘the golden boy of academe ... all heads turn when [he] enters the room’. There is ‘something wonderfully erudite’ about James Green – ‘and it didn’t hurt that, like [John F.] Kennedy, he cut a fine figure!’ In the introduction to the Jim Cullen interview, she uses the word ‘incredible’ three times on one page. And Harold Bloom is not alone in exciting her romantic ardour. With an implied giggle, she admits to having ‘a bit of a girl-crush on Camille Paglia’.

I understand the decision to set the scene for each interview: often the location is significant, and a description of someone’s home can convey something about them, though I don’t think a sentence like ‘He ushered me in when I rang the doorbell and we sat in a tastefully decorated living room full of beautiful ornaments’ pays its way. Waiting on the MIT campus to interview Chomsky, she quells her nerves by buying ‘a t-shirt that said Cutie pi and wish[ing] I had a science degree’.

You will observe that most of these interview subjects are white, male, and American. Of the eleven interviewees, in fact, the only woman is Paglia. Atherton defends herself pre-emptivelyagainst inevitable accusations of bias:

There were some failed attempts to connect with people … I was limited to the dates and location of my travels and work commitments. This explains why all of the interviews in this collection are with people residing or working on the east coast of America; this is where I conduct my business. It also explains, in part, the abundance of white, male middle-class writers, intellectuals and scholars. There would have been more women and a representative sample of other minority groups if all of the people I had approached had been available or had agreed to be interviewed.

She doesn’t say who these other people were, understandably, though it would be interesting to know. But the book is what it is, and I won’t waste words complaining that it is not something else.

Each interview averages about twelve pages, with plenty of white space on the page. The book is slender, at 151 pages. I did wonder who made the decision about available publication space, which meant that ‘entire questions [and responses] were edited out’. It seems unlikely that Australian Scholarly Publishing would have begrudged a few extra pages of Harold Bloom or Noam Chomsky.

The interviews themselves are structured but flexible. Certain questions are common to most or all: the relationship between the public intellectual or the creative writer and the academy; the link between teaching and research or activism; the roles and responsibilities of intellectuals. There are always additional questions formulated especially for the particular person (‘writer, scholar or intellectual’ is Atherton’s usual formula), and others are clearly prompted by the flow of the discussion. Bloom is sweetly avuncular and addresses Atherton as ‘child’, which she takes in good part. They agree that literary criticism can never be truly objective, that Tim Winton fails to impress, and that young people don’t read the classics enough. Imaginative literature is king: historian Jim Cullen modestly believes ‘that history is finally an imaginative act, but I guess I have too much respect for fiction writers to think I could ever be one’. A supporter of the canon, Atherton often asks about its current acceptance both in the academy and society. Dana Gioia, the ‘boyishly handsome’ chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, responds, ‘I’m not sure what it means to support the canonical literary tradition because the canon changes every year.’ Bad academic writing attracts constant criticism. Kenneth T. Jackson attacks the élitism of professors who think they should write obscurely ‘because we really don’t want the larger population to be part of the conversation’. Sociology professor Todd Gitlin claims that ‘to be a substantial French intellectual, one has to commit a certain level of bullshit. Foucault admitted it and Pierre Bourdieu admitted it’; while finding attempts to emulate their style laughable. Wholesale swipes at the evils of postmodernism (never defined) are common, especially in the later interviews. Chomsky calls it ‘unintelligible gibberish’ useful for keeping ‘intellectuals in their preferred status of conformist subservients [sic] to those in power’. Chomsky is fierce about almost everything; poet Paul Kane less so. Asked about the value of postgraduate creative writing degrees, he responds, ‘I would not stand up and denounce the writing programmes because of mediocrity, not at all. You look at any age and there are always going to be lots of people writing, most of who will be mediocre.’

Chomsky says much that is outrageous and provocative, but the prize for best entertainment in the book goes to Paglia. She mounts an all-out attack on just about everyone – Stephen Greenblatt, Michel Foucault, Naomi Wolf. ‘It’s warfare!’ she cries. ‘I don’t know if you know how ostracised I am in American academe? I hope you realise.’ Then, after a sustained demolition of feminist ideology: ‘they complain, complain, complain.’

I could have done with less of the wide-eyed ingenuousness of the introductions, but I’m all for interviews, and these are good ones. Atherton doesn’t make the classic mistake of stating her own ideas at length only to be rewarded with monosyllabic responses. She gives people plenty of scope to expand on their answers, and doesn’t cut them off when they embark on interesting digressions. It is certainly an unrepresentative group of writers, but they all have something worthwhile to say. Atherton’s style is sympathetic, bordering on the sycophantic, but that’s more conducive to communication than hostility. May she continue with her project, and come to regard these interesting high achievers as fellow scholars and human beings rather than godlike beings from another world.

Comments powered by CComment