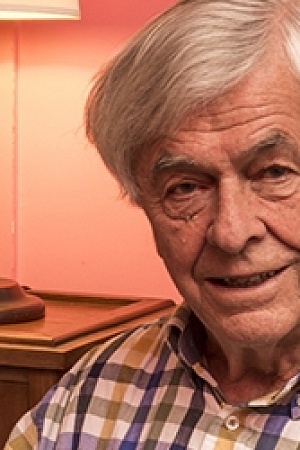

An interview with Frances Wilson

Frances Wilson lives in London and writes for the TLS and the New York Review of Books. The author of six biographies including Guilty Thing: A life of Thomas De Quincey and Burning Man: The ascent of D.H. Lawrence, she is currently working on a life of young Muriel Spark.

When did you first write for ABR?

I was invited onto the ABR Podcast last summer and subsequently asked by Peter Rose to review Dream-Child, a new biography of Charles Lamb.

What makes a fine critic?

A distinction needs to made between the critic and the book reviewer, because not all reviewers are critics. The reviews that run in the literary pages of newspapers – plot synopsis followed by puffery or condemnation – bear little relation to criticism, not least because critics read closely while reviewers tend to speed-read. Criticism is an art, and the finest criticism should be equal to its subject: a good critic should have a distinctive voice, a good ear, and a strong style. I like audacity and eccentricity in criticism, and I particularly admire those critics who are alert not only to the words on the page but to the ‘unconscious’ of the text – what is elided, repressed or not quite expressed in the writing.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.