An occasion like this teaches us that we each have our own Helen Daniel. I met my Helen nearly ten years ago, appropriately through writing. I had written a book on the Aztecs of Mexico. It was primarily an academic book, but because it was published by a university press with a branch here, and because Aztecs are Aztecs, it was widely reviewed in this country. The material was esoteric and its interpretation involved some complicated talk about theoretical issues in anthropology and history, so I was relieved when the local reviews were kind. Nevertheless, I read them with mixed feelings: how was it possible for people to understand the same printed pages so variously?

Then someone sent me a review written by someone called Helen Daniel from something called Australian Book Review, and I was amazed. Here was a reader who had read with extraordinary concentration and intensity. This person – this phenomenon – had traced every curve and wobble of a sinuous argument. Presumably from a standing start, she had outclassed the experts. And she had understood exactly what I was trying to do.

Naturally I wrote to her, we met, and slowly, awkwardly, we became friends. We didn’t know each other’s past; we didn’t know each other’s present. We knew nothing of each other’s social or domestic milieu. All we knew initially was something about how each other’s mind worked. It was like a friendship between adolescents. We would meet not in houses but in coffee shops and wine bars, and we interrogated each other more about hopes and possibilities than about actualities. We were both in a kind of interregnum: I had been transformed by illness into an invalid, and my occupation (academic) was gone; Helen had not long quit the second-hand book-and-furniture shop she and her companion Margaret Wintergest had run in Brunswick Street, Fitzroy, and was living by freelance journalism.

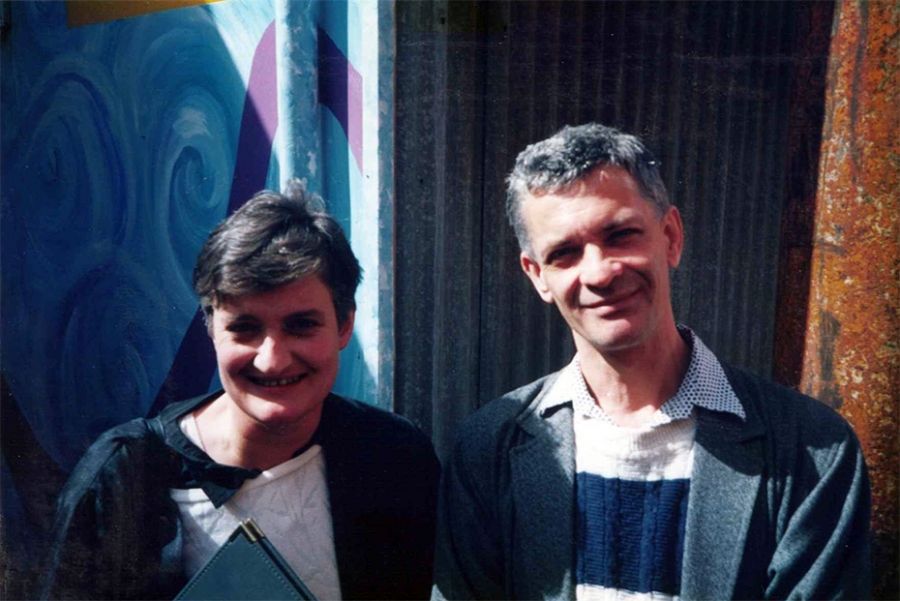

Helen Daniel (Editor of ABR 1995–2000) with Robert Dessaix, a contributor since 1981 (photograph by Peter Rose)

I still have only a thin notion of Helen’s early history: a cartoon narrative of a mother raising three children alone, moving around a lot; a gifted, rebellious schoolgirl; university; breakdown perhaps triggered by a failed affair; fragile recovery; rejection of university – and then a deliberate act of commitment to the active literary life, and to the care, protection, and promotion of Australian literature.

Helen was a single-minded patriot in literary matters. She was genuinely scandalised by my casual cosmopolitanism and my insouciant disregard of Australian writing. Accordingly, she undertook my education, and my redemption. I could no longer write history – I lacked both the physical and the mental stamina for such sustained enterprises – so Helen embarked on an endearingly transparent campaign to recruit me into the service of our national literature. She began cautiously, tempting me to write short stories: the very short ‘micro stories’ that Rosemary Sorensen had introduced at ABR. I did; one was accepted; I was delighted. I also started reading Australian Book Review.

Then in 1995 Helen won the position of editor of ABR. I saw her immediately before and after the key interview. Her mood was one of trepidation overlaid by jubilation, and punctuated by bouts of terror. She knew about writing and criticism. She didn’t know about editing. Rosemary Sorensen spent a month showing her the editorial ropes and soothing her fears, a kindness for which Helen was deeply grateful. And then she was on her own.

Editing ABR was an enterprise which Helen believed exactly suited both her capabilities and her determination to encourage the advance of Australian literary culture. She was a natural intellectual, excited by the play of ideas. I thought she sometimes took too much pleasure in provoking intellectual combats which sometimes generated rather more dust than light, but for her that was an integral part of the excitement. I also thought she undervalued her own talents. She knew she had a lucid mind; that she was marvellously attentive to the word on the page; that she was indefatigable when it came to unravelling puzzles and obscurities. But the talent she valued above all was the capacity to write with grace and power, and she was persuaded she lacked that. She was therefore eager to dedicate herself to the service of the people she thought possessed it, whoever they were, whatever their field. Hard on herself, she was unfailingly nurturing and indulgent towards her chosen ones. She also had a passion for system and order. As editor, she would be able to systematise the record of the most significant works published in Australia, not only in fiction and poetry, but in history, cultural studies, and social policy.

Meanwhile, she continued with her project to liberate me from my ivory tower: to transform me from a timid academic who believed she could write only as an expert into what Helen regarded as an altogether higher form of life: a Writer. My health and energy fluctuated, so she would wait patiently for signs of boredom or restlessness, and then she would pounce. Transfixing me with that extraordinary mesmeric gaze, she would dangle an artfully selected book before me, I would refuse, protest – and then succumb and review it. Persons previously unknown would contact me and ask me to contribute to collections of essays on strange subjects like death, and I would glimpse Helen’s hidden hand. When I had recovered sufficiently to consider writing history again, and decided to begin with a lightning raid into the stockade of the Australian past, it was Helen who happily published my essay on George Augustus Robinson. I doubt I could have published it anywhere else. She was training me in courage, possibly in recklessness: it was through writing a review for her (on Robert Manne’s The Culture of Forgetting) that I came to write Reading the Holocaust. And finally, while I had been content simply to contemplate the pile of assorted private writings I had generated over the course of my illness, it was Helen who gathered them up and took them to Michael Heyward, who turned them into Tiger’s Eye.

I tell you all this because it was only a few days ago, with the static of the everyday stilled in the silence of her death, that I realised the full weight of my debt to her.

Without her gift to me of ‘free’ writing, I doubt I would have survived this last decade, or not without damage. Because of her, I experienced it as a kind of liberation. Through all that lonely time she was a most faithful friend, who simply refused to acquiesce in my abdication from the responsibilities of the intellectual life. I don’t know how many other people she has coaxed along in the same way, but I suspect there were more than a few.

Then, with the magazine tossing up unexpected challenges which absorbed her energies and tested even her resources, her beloved companion Margaret fell ill, and at the end of a single terrible week, died. Margaret, somewhat older than Helen, had a developed talent of finding happiness in small things. She was also one of those rare beings who carried a zone of domestic warmth around with her: a warmth in which Helen had been securely enveloped through the years during which she had established herself as a major literary critic.

I was in the Far North at the time, and could follow what was happening only by telephone. Helen had reported Margaret’s death to me with unnerving calm, and for perhaps a fortnight afterwards she remained superficially serene. And then she collapsed, sliding helplessly into a vortex of loneliness and panic fear. The demons who had gone into hiding in her time of happiness were loosed again.

Over these last years I have watched her fight them. On a few occasions she came perilously close to destruction, but during this last year she had begun to defeat them: to become her own woman again. The Helen who farewelled me last May was merry, and full of plans. In the phone calls we were exchanging until a couple of weeks ago, she was vividly and vigorously herself again, deeply engaged in her work, and cheerfully pushing me into doing things I didn’t much want to do. The magazine was, at least for the moment, financially secure and of a sufficient number of pages, she felt she had marvellous support from the people she worked with in the office, and a board she honoured. In a burst of creative energy, she was extending ABR’s reach by a regular session on Radio 3MBS, a series of seminars at Reader’s Feast, and by launching competitions for reviewing and for short fiction. She had also returned to reviewing herself. Of course, all this increased her workload, but she didn’t care. The magazine was her life, and they were both thriving.

How did she win that victory? I think she achieved it because of several things. A small band of time-seasoned friends tended her through her illness with knowledgeable love, which is the best kind. I noticed something else in her accounts to me. As you know, Helen was a very private woman, fiercely independent in her dealings with most of the world – with one great exception. The exception was her sister Margaret, whom she expected to come to her in a crisis, whatever the difficulties, whatever the distance. And Margaret always came, sometimes scolding, always loving. Helen’s utter trust that she would come makes me think that Margaret had been getting her talented, difficult little sister out of scrapes for a very long time. I know that she and her husband, Joe Rich, have also given hours and days to the magazine when it has been in crisis, which at one stage was often. Helen knew them to be an ever-present strength in trouble.

Margaret and Joe continued to provide a family hearth for Helen even in her darkest times, when she cannot have been an easy guest. She came to value that home more and more deeply, and to rediscover pride in family, especially in her niece Megan, with whom she was particularly close. When I would begin boasting about my grandchildren, she would boast, rather shyly, about Megan, and about her small grand-niece Isabelle.

She was fortunate to find a psychiatrist who was as intelligent as she was – she tested him hard on that issue – and whom she came to trust. He got her to write again, and to take an interest in the puzzle of why her mind worked as it did. She came to depend on their regular meetings.

She was also helped, I think more than she realised, by the forbearance and the delicacy of the people she worked with, especially the staff in the office of ABR, who came to admire and to love her, but also the wider circle of writers and reviewers. We all remember how she was on the bad days, like a sad little owl staring blindly out of a vast desolation, but even at her most desolate and isolated, the people around her treated her with respect, tenderness and tact.

But mainly she was saved by her own magnificently tenacious courage. She lived through weeks and months of bitter loneliness and bouts of existential dread with a mute stoicism which appalled me. I could not understand how she endured it. And in the end she triumphed, and faced her demons down.

I don’t know what will happen to the magazine now. The staff and the board will do their best to save it, but we can’t hope for another Helen. Her absence will impoverish my life, as it will yours. But she was a warrior and a warrior who knew she was going to be victorious in a fatal struggle.

Plains Indians used to have a saying to encourage their comrades when they rode out to battle. They rode in the hope of victory, but with the knowledge that in mortal combat death is always near. So they would say: ‘Brother, this is a good day to die.’ I hope for Helen it was a good day to die.

This is an edited version of the speech that Inga Clendinnen gave at Helen Daniel’s memorial service at Newman College Chapel.