- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

You can’t escape the black square with the ominous slit: it’s about as familiar and inevitable in Australia as the icon for male or female. Ned’s iron mask now directs you to the National Library’s website of Australian images. There it is, black on red ochre, an importunate camera, staring back as we look through it ...

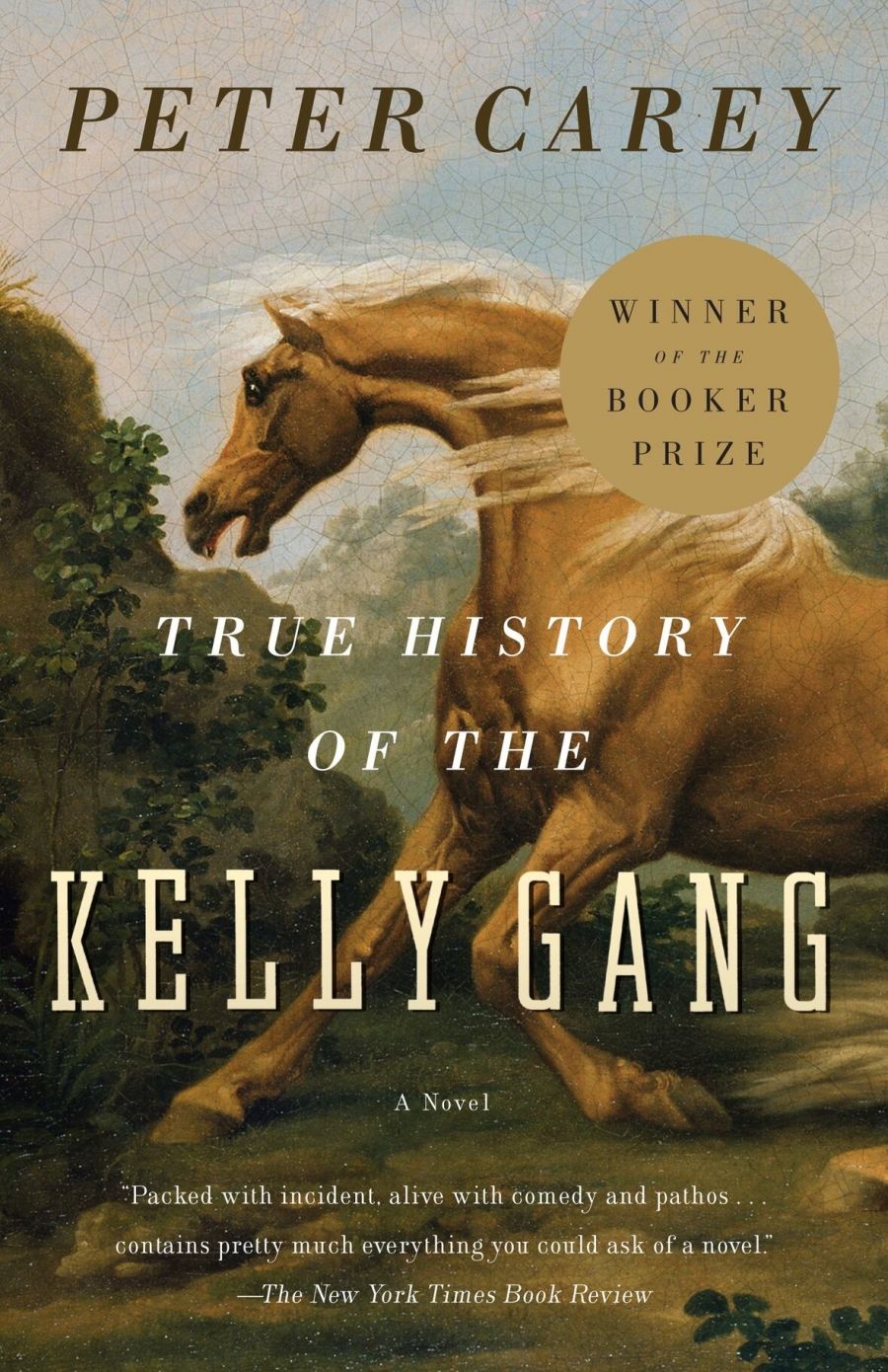

- Book 1 Title: True History of the Kelly Gang

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $50 hb, 401 pp, 0 7022 3167 3

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/XbkVg

Carey’s Ned also has a woman/wife and a child. The wife is dispensable. Carey ships her off to California so she is not around to complicate the determined tragedy of the last stand at Glenrowan. But the child is the destined recipient of the first person narrative of the novel, the thirteen bundles, variously manufactured, bound and scrawled, of ‘true history’. She is also their rationale: ‘Parcel 1 ... National Bank letterhead ... my dear daughter you are presently too young to understand a word I write but this history is for you and will contain no single lie may I burn in Hell if I speak false.’

The ‘True’ of the title is a multilayered, serious tease. Carey’s story keeps intersecting with historical and traditional material. He magpies as and when it suits his imaginative purpose and structural intent. He quotes, often to prefigure. His Ned at age fifteen concludes that ‘such is life’, when he witnesses the fate of a snip-horse, an accidental casualty of one of bushranger Harry Power’s exploits. ‘She had taken the bullet high in her shoulder and when she cooled would certainly be lame for good. [Ned is shot in the right leg at Glenrowan.] Thence only death a sledgehammer between her blindfolded eyes such is life.’

There is a little too much of such flagging in the novel. It reads like rigging fate. But that, I think, is the way Carey builds his figure of Ned: as a man destined, by extraordinary capacity and circumstance, to a kind of monomaniacal martyrdom.

Carey twists the record. His Ned kills Mr Murray’s heifer and the father, John ‘Red’ Kelly takes the blame – and the fatal jail term for it. It was actually John Kelly who killed and butchered the heifer. But the incident in Carey gives substance to Ned’s sense of responsibility and of doom.

He co-opts Irish myth. Ned hears a banshee and immediately finds an old man dead. Tom Buckley in his miner’s hut: ‘dressed in the uniform of some foreign king I don’t know why. The uniform were very old and Tom Buckley dead an old bachelor and no wife to mourn him.’ (The incidental detail of the uniform is typical, inspired Carey.) He explains the wearing of another kind of uniform, the dress, associated first, and shamefully, with his transported Irish father, John Kelly, and later worn by Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Mary Hearn, Ned’s woman, ‘knows’ what it means (Carey has been consulting Irish historian Roy Foster) and so chastises the boys with a history lesson in bizarre Irish vengeance. ‘This costume is worn by Irishmen when they is weak and ignorant.’ What follows is an appalling Irish tale of torture and cruelty, which Carey tells marvellously.

The voice of the narrative, Ned’s first person, uncomma’d, untutored, lyrical and sinewy sound had its source in Carey’s first encounter, decades ago, with Kelly’s Jerilderie letter. It’s a remarkable and sustained technical achievement. Huckleberry innocence by Carey facility out of historical record. Of course, it appropriates the high public rhetoric of the Jerilderie letter to an anachronistic private purpose, but that is Carey’s fictional prerogative. If it strains at times (‘I were a plump witchetty grub beneath the bark not knowing that the kookaburra exists unable to imagine that fierce beak’), it’s because Carey has a plan for his Ned rather than because he can’t hold his own tune. He can. And it is a wild tune.

But I do wonder whether it isn’t a tune that will be better heard outside Australia than in. Our problem might be that we simply know too much.

Comments powered by CComment