- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird wrote The Secret Life of Plants (1975), many critics labelled their attempt to prove a spiritual link between people and plants as mystical gibberish, with a New York Times review chiding the authors for pandering to charlatans and amateur psychics ...

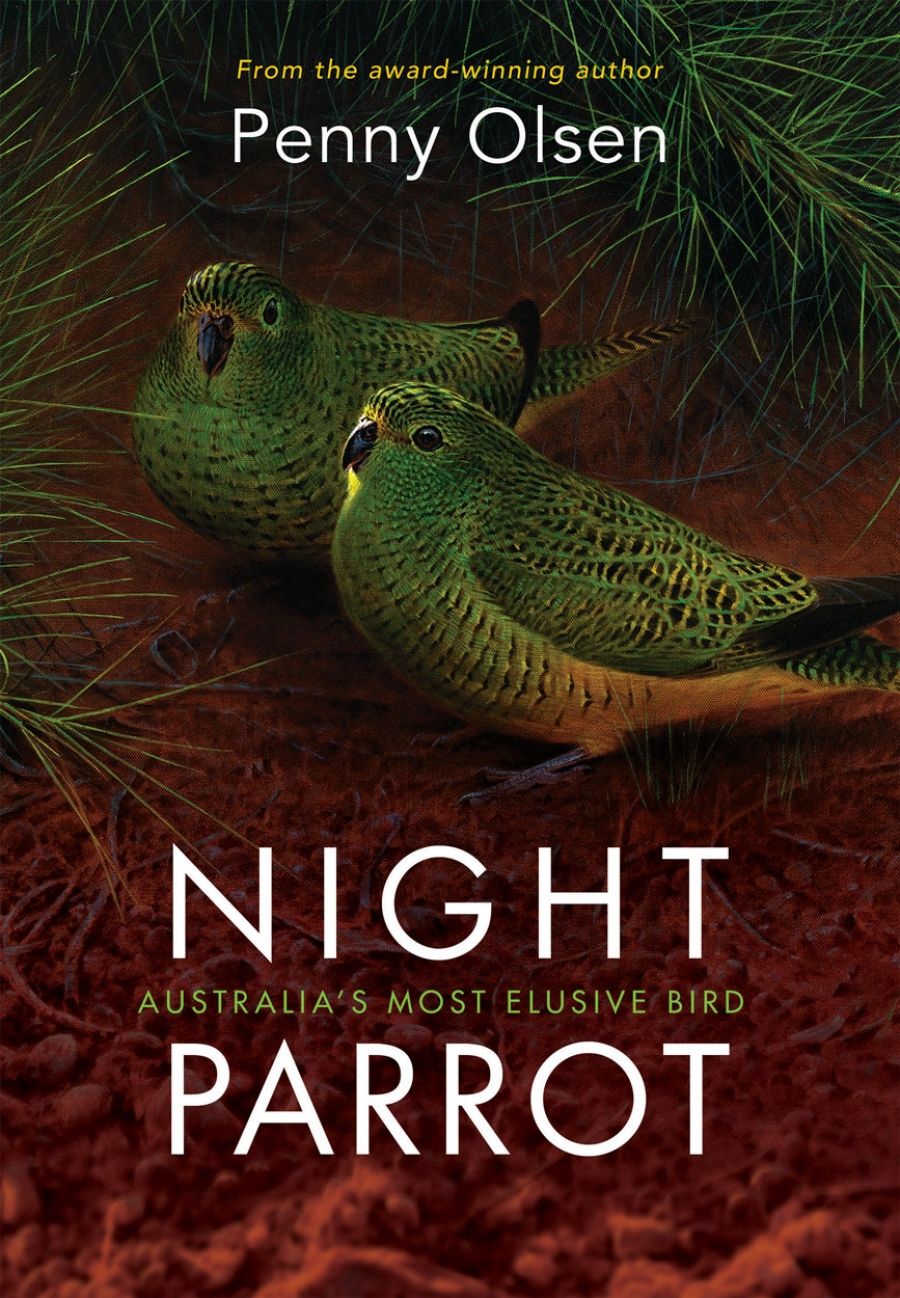

- Book 1 Title: City of Trees: Essays on life, death and the need for a forest

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $24.99 hb, 312 pp, 9781925773439

When Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird wrote The Secret Life of Plants (1975), many critics labelled their attempt to prove a spiritual link between people and plants as mystical gibberish, with a New York Times review chiding the authors for pandering to charlatans and amateur psychics. The review noted that although Tompkins and Bird made a fascinating case for plant sentience ‘suspended in the aspic of their blarney, it all looks equally improbable’. In the ensuing decades, more books have been published on the life of trees and their relationship to humans, some of which have sold well and been enthusiastically received by critics. Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What they feel, how they communicate – discoveries from a secret world (2016) topped bestseller lists and earned him a flattering interview in the profile pages of The New York Times.

While an interest in trees has certainly emerged among an educated readership, Sophie Cunningham’s collection of essays could be viewed as a heartfelt and timely postscript to much of this tree talk. It’s all very well to read books on trees, but what are we doing to save them and the animals and ecosystems that rely on them for survival? What will become of the groves that cannot replace their felled compatriots fast enough? What irreparable damage will climate change do?

Naturally, it’s a political book, but it’s also touchingly personal, tracing Cunningham’s encounters with trees as she moves across continents and her hometown of Melbourne. Cunningham’s wide roaming acts as an entry point into stories on the trees, gardens, and plants she discovers during her lengthy constitutionals and sojourns. In ‘Escape to Alcatraz’, Cunningham volunteers as a gardening worker over two bird-breeding seasons on the San Francisco Bay island of Alcatraz. She photographs the snowy egret colony and takes a particular interest in ‘survivor plants’, those two hundred or so species that grew defiantly through the forty-year period between the closure of the prison and the start of the garden’s maintenance program. In ‘Tourists Go Home’, she touches on the deleterious consequences of travel for the trees and the broader environment. Cunningham used to preference travel over everything else – superannuation, sensible purchases, meaningful savings – but now she isn’t so sure. Almost nine million people visit Barcelona each year, and it’s getting harder to find places where the locals don’t want you to leave. Tourists, of course, also come in the form of animals and plants, which can sometimes have a severe impact on the biodiversity of the region. In ‘I Don’t Blame the Trees’, Cunningham displays a talent for great observational detail, noting that the debate as to whether eucalypts should be removed from California’s Angel Island is loaded with inflammatory phrases such as ‘immigrant’, ‘invader’, and ‘refugee’. She resists championing the cutting down of non-native species simply because they don’t support local flora and fauna, wondering instead, quite astutely, what will replace the old trees after they are removed and pointing out that these days all of us are from somewhere else anyway.

Cunningham leavens her firsthand stories with summaries of scientific research and interviews. The result is an intriguing mélange of personal journey and journalism. The giant sequoia, we learn, are among the world’s oldest trees and their final numbers can be found along a belt of the western Sierra Nevada. When Cunningham walks through a grove of them, tears streaming down her face, she thinks, ‘I would lay down my life for you’. Indeed, language often fails Cunningham, an accomplished prose writer, when she would like it the most. Standing before old-growth trees, reaching for description, her mind stalls before their majesty. She sketches the trees instead, but even this proves challenging, with Cunningham left to wonder, ‘Is it possible to draw, or write, a forest?’

Sunlight coming through some redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) in the Muir Woods National Monument in California (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Sunlight coming through some redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) in the Muir Woods National Monument in California (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

There are a range of statistics deployed throughout the essays to emphasise the threat that trees face, but a handful stand out: almost all of the baobabs from Africa – many of them more than two thousand years old – have died; and it’s estimated that koalas will be gone from the wild by 2050. Australia fares especially poorly in looking after its habitats, with thirty-five per cent of all global mammal extinctions since 1500 occurring in Australia, yet we have not listed a critical habitat for protection for more than a decade. Furthermore, less than two per cent of the mountain ash estate in Australia is now old growth, prompting Cunningham to ask, ‘In what universe would a reasonable person think it was okay to cut down an 800-year-old tree and reduce it to a few hundred dollars’ worth of woodchips? Ours, apparently.’ Trees do grow again, Cunningham notes, but climate change is accelerating climate variation, making it more difficult for organisms to adapt.

While researching the essays, Cunningham experiences a succession of personal traumas, which become a way of framing the persistent grief she feels for the loss of global species and habitat. Cunningham and her wife, Virginia, return from living in San Francisco at the height of the internecine debate over gay marriage in Australia, ‘which seemed to devolve into the right of LGBTQI teachers to teach and the right of bakers to refuse the supply of wedding cakes’. While she is writing many of these essays, her father, John, who was originally her stepfather before adopting Cunningham and her brother, is in a high-care ward in Melbourne with frontal lobe dementia. She flies home to be by his side at the end, and he dies surrounded by family. Not long after John dies, her biological father, Peter, dies from Parkinson’s disease.

Following these two losses, Cunningham experiences months of insomnia; she takes comfort in animals and the living world. She opens windows around dawn to hear the birds, or rain, or building works, ‘anything other than the sound of nothing at all’. Biologist E.O. Wilson has described the post-extinction landscape as the Eremocene age, or ‘The Age of Loneliness’, and this is what Cunningham really fears: the emptiness that follows when a vital connection – be it with a father or the natural world – is severed.

In this sense, these fine essays convey what factual reporting on the threat of climate change and the loss of habitat cannot: something beautiful is dying, something precious and monumental may be lost forever. The temptation these days is to look away from the sadness, to rant on Twitter about the threat to old growth rather than to visit extant forests, but Cunningham is doing nothing of the sort. The final essay, ‘Mountain Ash’, ends with a visit to ‘Ada’, who has no surviving old-growth companions around her. Cunningham is aware of scientists’ aversion to overstating the consciousness of trees, of how this leads people to jump to conclusions about their supposed personalities. She is, however, unapologetic, telling Ada, ‘I will drive, I will wade, through fields laid waste by clear-felling, through ancient and perfect rainforest, to stand before you, my queen.’ The effect of this highly confessional approach is oddly mesmerising, and while Cunningham’s essays are accounts of her intimate encounters with trees, her gift is in making them feel like they are our stories as well.