- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Night Parrot by Penny Olsen is more than a biography of a bird that spent most of the twentieth century successfully hiding from people. It is a historical biography of human determination and obsession, and of the ways in which this bird has acted as a catalyst for transitions between those two psychological states ...

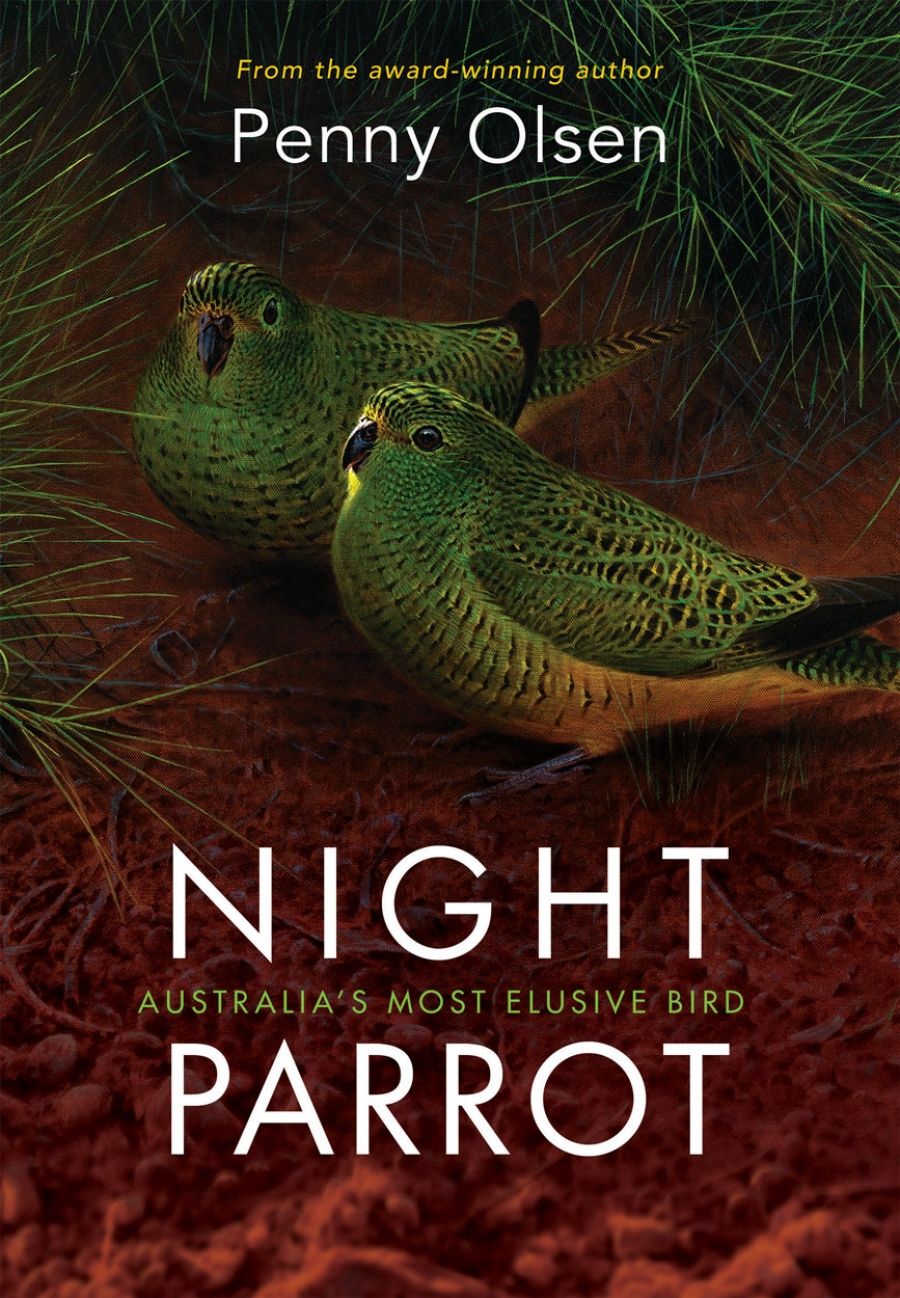

- Book 1 Title: Night Parrot

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia’s most elusive bird

- Book 1 Biblio: CSIRO Publishing, $49.99 pb, 368 pp, 9781486302987

Night Parrots (Geopsittacus occidentalis) are hard to find. A predominantly desert species, they tend to spend the day in burrows under spinifex or samphire clumps, emerging at night to feed on grass seeds. The first recorded collection of a Night Parrot took place on Charles Sturt’s expedition to northern South Australia in 1842. Sturt had been commissioned by the governor of the colony to explore the north for sources of reliable water for agriculture. Sturt’s determination (obsession?) to track northward-flying waterbirds to an agricultural paradise was a failure, and when he returned to Adelaide, his health was broken. But he had brought back a specimen of a new species, the Night Parrot, shot by the young John McDouall Stuart in samphire flats, northeast of Lake Eyre.

Unfortunately, the specimen wasn’t recognised as anything new. Sturt’s birds were sent for identification to John Gould, the British expert on Australian birds. In his published journal, Sturt recorded it as a similar-looking species, the Ground Parrot, that inhabits east-coast salt marshes, suggesting that Gould didn’t see or didn’t look carefully at the specimen. Rightfully miffed, the bird vanished down a hole, finally showing itself to Australian parrot expert Joseph Forshaw in 1971 at the Liverpool Museum in the United Kingdom. Gould, who was sent another Night Parrot from Western Australia in 1855, realised in 1861 that it was something new, named it, but didn’t twig that Sturt’s bird had been the same thing.

Steve Murphy holding the male Night Parrot freshly removed from the mist net on 6 May 2016 (photograph by Rachel Barr)

Steve Murphy holding the male Night Parrot freshly removed from the mist net on 6 May 2016 (photograph by Rachel Barr)

Meanwhile, most of the action returned to South Australia, courtesy of the discovery by Frederick Andrews, the South Australian Museum’s collector, of a reliable source of Night Parrots in the Gawler Ranges, north-west of Port Augusta. Olsen’s count is that, globally, twenty-two of the twenty-eight known museum specimens were collected by Andrews. Most of these were from the Gawler Ranges in the 1870s. Andrews comes across in his letters and a short written article, reproduced in the book, as the least obsessive of all the Night Parrot principals.

A large part of the book deals with other and later searches, grouped by state. Their interest lies largely in why most failed to find the bird. Much effort went into Western Australia and what became the Northern Territory. Despite the effort – large-scale expeditions, extensive and intensive consultations with Indigenous communities, public advertisements – there were few positive results among many misleading ones. Some people, including Indigenous groups, certainly knew the bird, its names, and habits. Some supposed bird remains were real. These sections of the book are an engaging exposition of the human menagerie of the times and places – some people to admire, some obviously obsessed by the search. Nonetheless, despite elaborate and costly investments, frustratingly no live specimen has ever been taken from the Northern Territory, and only three from Western Australia. None, too, from New South Wales or Victoria, although historical accounts from north-western Victoria have been accepted as reliable.

In spite of probable sightings near the original Lake Eyre site in 1979, it took Queensland to drag the story into the late twentieth and the twenty-first centuries. Road kill found near Boulia in 1990 testified to the Night Parrot’s existence, but not to a location of original impact. Then, in 2006, a corpse on a roadside with feathers on an adjacent barbed-wire fence focused attention on Diamantina National Park and surrounds.

It took until 2013 before incontrovertible evidence of a live Night Parrot was presented publicly. This came in the form of film presented by a non-scientist, but with an endorsement from the well-credentialled scientist Steve Murphy. This was tricky, as the presenter was John Young, an amateur who had polarised the Queensland birding community with regular claims of seeing unlikely things (like Paradise Parrots) and by presenting unconvincing images of a ‘new species’ of Fig Parrot.Nonetheless, there could be no doubt that the film was of a live Night Parrot. Despite Young’s determination to keep the location secret and to exclude governments from management, key information eventually leaked out. South-west Queensland called.

Extremely valuable outcomes from the newly discovered population have emerged: recorded calls can now be used in surveys, so it is possible not only to recognise a call remotely recorded in possible habitat but also to play calls and listen for answers. This has led to more populations being discovered and potentially protected in arid Australia.

The most unwelcome outcome has been fake news of unreliable ‘findings’ and bad news that birds may have been unethically handled, reflecting something other than determination to do the best for the bird. Thanks to the revelations first presented in this book, which triggered a major enquiry, the way that the species is managed, and by whom, is being rapidly reshaped.

Comments powered by CComment