- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Bumper on the go-go’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In August 1999 the Melbourne art collective DAMP staged an argument that turned into a glass-smashing fight at an exhibition opening of its work at 200 Gertrude Street. Peter Timms, writing in The Age, described this event, which in former times might have been called a ‘Happening’ and today would be recognised as a ‘Pop-up project’:

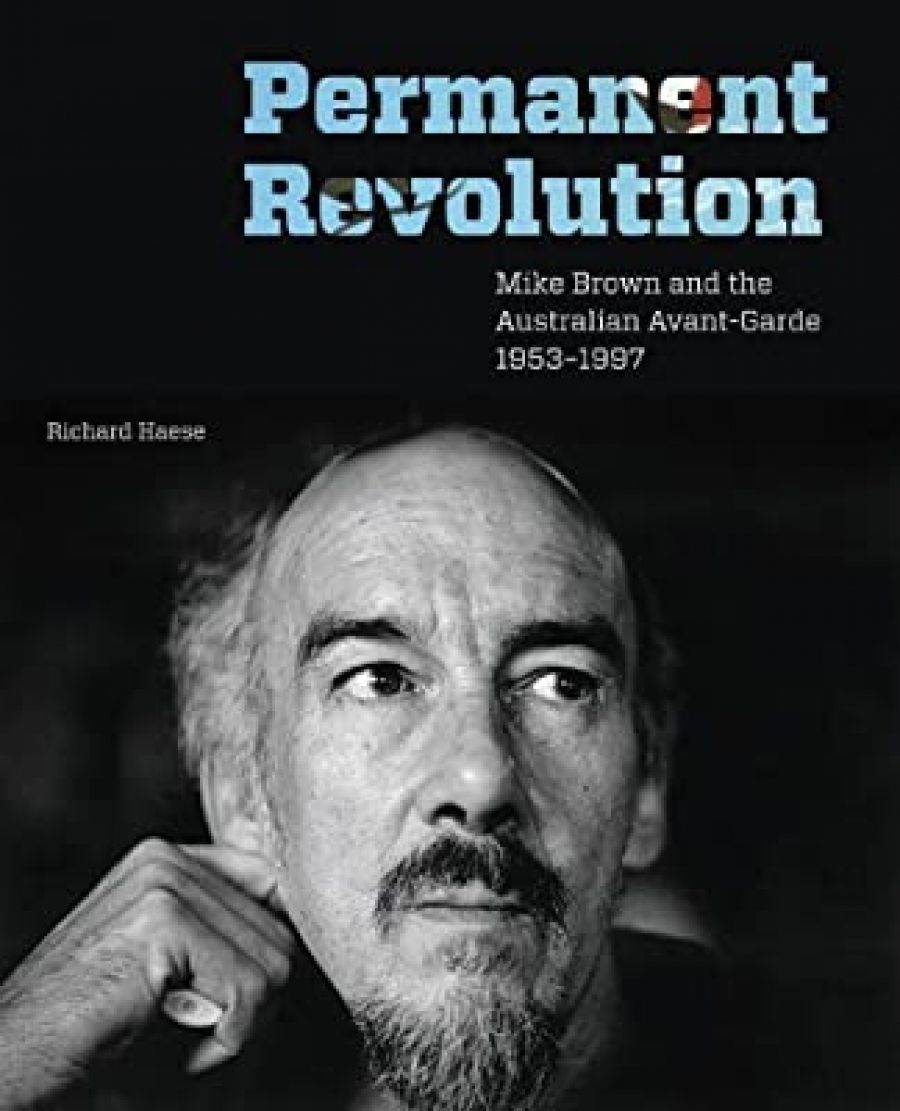

- Book 1 Title: Permanent Revolution

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mike Brown and the Australian avant-garde1953–97

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $49.99 hb, 304 pp

A young couple started arguing. It was unpleasant, but at first didn’t cause too much disruption, apart from the odd disapproving look. Then the dispute got louder and more insistent and one or two others became involved. A young man had a glass of wine thrown in his face, then the shoving started. Glasses and bottles were knocked over and smashed, and a girl was pushed through the wall. The installation work in the front gallery, by a group of artists calling themselves DAMP, was almost completely wrecked. Only gradually did people start to realize that DAMP’s installation was not being destroyed but created.

Mike Brown would have enjoyed that. He was an iconoclast, an anarchist, a Dharma Bum, and a totally free-thinker. His work was also, famously, on the receiving end of a more deliberate attack. On page 180 of this page-turner by Richard Haese, there is a fantastic image of Sydney Morning Herald art critic Donald Brook hurling a mud pie at an Op Art painting by Brown. The year was 1972, the place was the seminally important Watters Gallery, and the back-story was the Vietnam War, nuclear escalation, experimentation with drugs and alternative lifestyles, and a battle within the Australian art world between abstraction and figuration.

Imitation Realism was the movement incubated in a terrace house in Sydney’s Annandale. Brown, Colin Lanceley, and New Zealander Ross Crothall introduced collage, assemblage, and installation art to Australia for the first time. At least that is the long bow that the blurb attempts to draw. I was sceptical at first, but the more I read this thoroughly researched and beautifully designed book, the more I came to agree. These artists, roped together intellectually and emotionally like Picasso and Braque during the pioneering days of Cubism, were also the first to ‘respond in a profound way to Aboriginal art, and to the tribal art of New Guinea and the Pacific region’. Yet the key model for the Imitation Realists, as Haese points out, was dada, and the dadaists’ embrace of the primitive and ‘the demotic’.

To add to this wayward curriculum vitae, in 1966 Brown became the only artist in Australia to be prosecuted successfully (the key word) for obscenity. Once the press became involved, it turned into the same sort of dark circus that Bill Henson and others would recognise today.

In a brief period of on-and-off relationships during the previous year, Brown’s marriage to the fashion designer Ann Cole (who later took the professional name Annie Bonza) ended after three days of continuous arguing when he announced his love for ‘the ideal independent woman’, Vivienne Binns. But this only lasted, with intensity, a few weeks. By August 1965, Haese writes:

Brown was alone and renting a couple of rooms in a large terrace house in Oxford Street. In expectation of a visit to Sydney by John Reed, Brown wrote to Reed: ‘I think you’ll find my painting in its usual state of utter chaos – a mass of half-digested ideas furiously competing with each other for space on the canvas … The threat of an exhibition in November at Gallery A will no doubt force an uneasy truce … but as time goes on I find myself more and more inclined to ‘cut up rough’ with art rather than settle down.’ In the event, Brown’s cutting up rough with art with his exhibition Paintin’ A-Go-Go, at Max Hutchinson’s Gallery A in Paddington, proved a perilous and traumatic excursion into the realm of the political and the scatological.

Every circus, dark or light, needs its clown. Cue the chief of the Darlinghurst vice squad, Sergeant ‘Bumper’ Farrell. He arrived two days before the exhibition was due to close. There had been complaints made about the depiction of genitalia and the use of various four-letter words. A grainy black-and-white photograph from Sydney’s Daily Mirror is reproduced in the book. It shows the detective leaving the gallery under the headline ‘It’s Bumper on the go-go’.

On the opposite page, Hallelujah is reproduced, one of the five paintings (out of a total of thirty-three) that were said to have caused the offence. It has a Jean-Michel Basquiat graffiti-like energy to it, avant la lettre, and would have looked pretty fresh hanging in an East Village gallery twenty years later. Elwyn Lynn described the exhibition as ‘a technicolour Walpurgisnacht’ and noted that ‘gaudy ribbons of paint writhe, whorl and cavort’. Among them, in different scripts, phrases such as ‘Stuffit Upya’, ‘Shit! Fuck!’, and ‘Arseholes to you, too, Darlingg’ (sic) flash like neon signs across the canvas.

Mike Brown, Lullaby in the Twilight Zone, 1965, synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 122 x 92 cm, Heide Museum of Modern Art

Mike Brown, Lullaby in the Twilight Zone, 1965, synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 122 x 92 cm, Heide Museum of Modern Art

At this point, the notorious Oz trial in London was still unresolved. Potentially long jail sentences hung over Richard Neville, Martin Sharp, and Richard Walsh. What would happen in Sydney, especially given that some of the paintings were Brown’s deliberate response to the Oz trial? I urge you to read this book to understand fully the complexities of this case, and indeed, the whole of Brown’s ever-changing life. Briefly, he was sentenced to three months’ hard labour. Many came to his defence, including Bernard Smith and, even more passionately, Richard Larter. There was an appeal. While the conviction was upheld, Judge Justice Levine reduced the sentence to a less back-breaking $20, remarking on the unlikelihood ‘that he would again commit such an offence’. As Haese writes, ‘Those who knew Brown felt less sanguine regarding the final remark.’ Many years later, Brown would predate Chris Ofili in the same way as he had Basquiat, by using soft-porn images in his collages. Later still, when he was awarded what became known as a ‘Keating grant’, an Australian Artists Creative Fellowship, he bought an Apple Power Mac with advanced graphic functions. In a later section of the book titled ‘Cyber Sex’, he is quoted as warning his brother Julian that ‘Very likely in the next year or two I’ll earn a gross form of notoriety as an artist determined to press “moral” ie sexual censorship in art to its limits.’

Eventually, Brown would be felled not by a judge, a detective, or an enraged art critic, but by a double brain tumour. The latter part of the book is excellent on his final years in Melbourne, his retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1995 – I remember it well, and with excitement – and his many friendships and relationships, the last of which was with Nicky Mitchell.

A bright star stencilled on a wall appears on the back of this volume, and the photo credit places it as Mike Brown’s house at 22 Grant Street, North Fitzroy. Curious, I tapped it in to Google Earth and was taken there immediately. A second click took me right in to the star on the wall, obviously repainted, but as good a gravestone as you could wish.

Comments powered by CComment