- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

With Tim Burstall’s death in 2004, Australia lost a key figure in the rebirth of a distinctive and energetic national film industry. While critics disdained his rough ocker populism, Burstall’s Stork (1971), Alvin Purple (1973), and Petersen (1974) were significant commercial successes and demonstrated the viability of a product willing to show Australians to themselves. Burstall argued that a film industry without artistic standards was undesirable, but that so too was an industry cut off from market considerations.

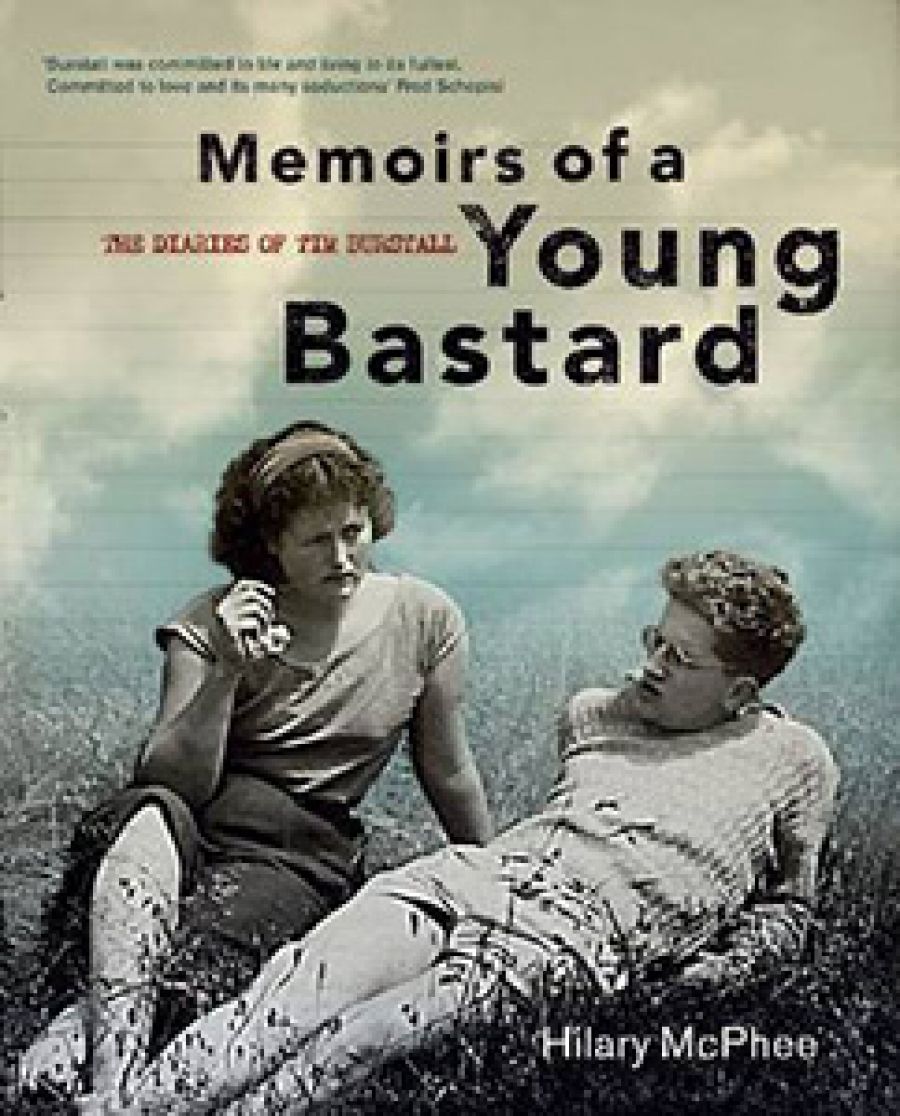

- Book 1 Title: Memoirs of a Young Bastard

- Book 1 Subtitle: The diaries of Tim Burstall November 1953 to December 1954

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/memoirs-of-a-young-bastard-hilary-mcphee/book/9780522858143.html

Burstall launched his film career in 1960 with the engaging black-and-white short feature The Prize, which featured his young sons Tom and Dan and a score by the Melbourne composer Dorian Le Gallienne. That film was honoured at the Venice Film Festival, the first of many awards Burstall would receive. In his late-flowering career as a director and film-maker, he brought immense energy and a passionate commitment to the Australian film industry; he is remembered as one of its heroes, a star-spotter, a superb collaborator, a passionate advocate. His influence continues in the work of many significant Australian writers, actors, and directors who gained their start working on a Burstall film.

But it is a younger, crasser, and less formed Burstall that emerges in the self-conscious but not always self-aware diaries that he kept as a rampaging young stud, cutting a swathe through staid and conformist Melbourne in the uneasy Cold War years of the early 1950s. While the diary is more than a record of carnal pursuits and conquests – the action is set against the lively background of left-leaning and radical politics, of Melbourne’s postwar artistic ferment, and of a new young intellectual community beginning to find its voice and influence and to define new ways of living – Burstall himself lives for the moment and for the next encounter.

Married then to the remarkable Betty Burstall (who later founded the innovative and influential La Mama Theatre in Carlton), the diarist lived as a free agent. He sought love and sex wherever he could, sometimes clumsily and always without regret or apology. The Burstall marriage was famously or notoriously an open one, with both parties free to pursue their romantic or sexual inclinations, something Tim Burstall did with gusto and bravado, while Betty (though she was the first to stray, in a short affair with the painter John Perceval) seemed more equivocal. Now, in her eighties, she expresses no regrets at the life that was lived.

When Burstall tried unsuccessfully to publish the diaries in the 1980s, he gave them the title The Memoirs of a Young Bastard Who Sunbaked and Rooted and Went to Branch Meetings. This offers a partial truth, but it conceals a more vulnerable, less certain, and wounded persona in a personal history that casts its shadow over a pungent and sometimes brutal narrative of life and events. In seeking to understand the writer’s candour, some allowance needs to be made for the public humiliation incurred when the seventeen-year-old Burstall, at his parents’ instigation, was declared a ward of the court (a ‘bastard’, as Tim saw it) to prevent his marriage to fellow arts student, the young Betty Rogers, then pregnant with their first child.

The scandal of the pregnancy had already seen Burstall thrown out of his college at Melbourne University, but the court case that followed was ugly and the coverage by a prurient press sensational. Burstall’s family severed their connection with their errant son, a rift that was never fully repaired. Burstall married Betty, but their first child, born prematurely, survived only a few days. The scars inflicted on the young Burstall may explain his devil-may-care attitude toward life, which is manifest in the diaries he began writing in November 1953 (aged twenty-six) and continued for three years, at a rate of some five hundred words a day, until the final entry on New Year’s Eve 1956 (the published diary runs for just over twelve months). Editor Hilary McPhee speculates that another explanation for Burstall’s free-wheeling sexual adventuring may owe something to Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male (1948), a book that unleashed a new liberality in sexual matters. Follow your lusts, went the maxim. Burstall for one wasn’t going to die wondering.

If the expiation of personal pain was one deep and possibly unacknowledged motive for these diaries, and the recording of frank lust another, Burstall also comes across as a relentless, even dogged observer of the times and milieu in which he lived – perhaps incipiently already the film-maker he later became. Friends recall him quoting the famous declaration from Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin ‘diary’: ‘I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking […] Someday all of this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.’

But as McPhee suggests in her sensitive and thoughtful Introduction, Burstall was no passive recorder. While his ‘camera’ rolled, the gaze of its operator was mercilessly, sometimes treacherously, turned upon his neighbours, friends, and acquaintances, and on a rich cast of artists, writers, philosophers, musicians, and academics. Confidences are shamelessly betrayed, and the diarist’s jibes are sometimes shockingly cruel, cutting, and dismissive. Consistently though, shrewdness cuts through cant, hypocrisy, and pretension to produce some memorable observations: Brian Fitzpatrick with his ‘heavy Irish drunk’s face’; Ian Turner sacrificing his intelligence and integrity to turn himself into an efficient Communist Party functionary; Labor Party stalwart Betty Marginson lustily declaring her love of money; and Robin Boyd – well dressed, blonde hair, a gentle smile – ‘the mild, impenetrable Boyd manner’ lit by a lively, questing intelligence.

Burstall’s gaze was turned too on his wife and his lovers and – whether intended or not – as unsparingly on himself. Complex and conflicted, he is revealed as a product of his times. The Burstall we see revealed in these diaries is sexist and chauvinistic, casually and carelessly homophobic, brutal in judgement and with a superiority that derives as much from his education at Geelong Grammar as it does from his essential scepticism and his lively, impatient intelligence. But at the tender heart of these diaries (for there is one) is the portrait drawn of his most tormenting affair with the beautiful and cultured Fay Rosefield, then a student of Russian literature at Melbourne University, later a concert pianist and academic: as Fay Zwicky, she has built her own reputation as a poet and short story writer. Ardent but fragile, full of longing but in heart and mind ultimately unrequited despite all those trysts by the Yarra, this affair was constrained by the ties of family and commitment that would endure against the odds and with their own particularity until the end of Burstall’s life. At one point Tim and Betty talk intimately and frankly of their respective adulteries: ‘“It was wrong of you to have John,” I said, “and me to have Fay.” “Yes,” Betty said […] “But I’m going to give Fay up,” I said quietly. “I don’t expect you to,” Betty said.’ The affair didn’t thrive, and while the Burstalls’ marriage was often tempestuous, their essential union endured.

The central landscapes of the Burstall diaries are the city of Melbourne with its pubs and cheap restaurants, its galleries and bookshops, its lofts and artists’ studios, the river bank; and Eltham, the bush suburb on the city’s outer fringe. There the ‘arties’ and the ‘intellectuals’ were forming a new élite, even though it was a struggle to make ends meet: mudbrick houses became the vogue (the Burstalls built their own); new paths were laid; fruit and vegetables were grown and goats milked; pots were thrown, decorated, glazed, and sold; and promiscuity and adultery, in Burstall’s telling, became a way of life. ‘Eltham’s like a madhouse, sexually’ he declared in his entry for 21 January 1954.

In this handsome Miegunyah Press edition, Burstall’s lively, if surely sometimes contestable, evocation in words is complemented by a superb selection of photographs. While many come from public collections, the best – drawn from the archives of the Burstall family – have an immediacy and vitality that will make the past and its people vibrantly alive to those who have merely heard hints of stories long since transmuted into myth and legend. And if the raw negatives that are the diaries still await the historian’s careful developing, printing, and fixing, Burstall gives form and substance to much that is dispersed and lost in the rough and ready business of living.

Comments powered by CComment