- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

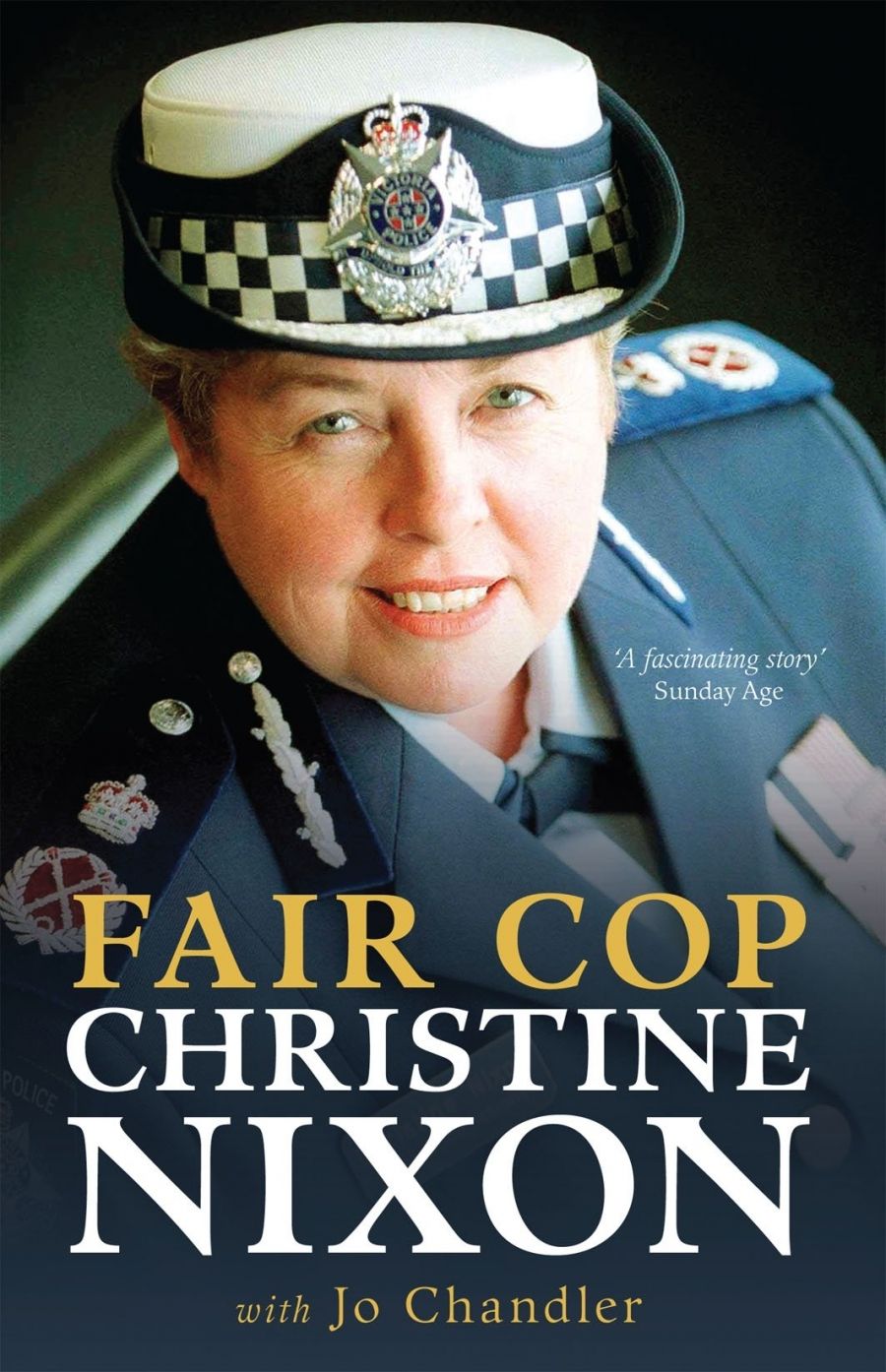

Christine Nixon belongs to the postwar generation of women who were not content to be passed over in favour of men when they entered the workforce, and who refused to accept the notion of a glass ceiling. Germaine Greer changed all our lives; empowered us as second-wave feminists. Nixon rose to the top in two of the most masculine organisations in Australia, the New South Wales and Victorian police forces. She became the first female chief commissioner in Australia, one of a handful around the world. Sadly, her legacy is now compromised. Fair Cop explores how this happened, and why.

- Book 1 Title: Fair Cop

- Book 1 Biblio: Victory Books, $36.99 pb, 388 pp

Although billed as a memoir, Fair Cop reads like autobiography. If you want to know the details of any claim or counter-claim, just consult the thorough index. The tone of the work is measured and dignified – surprising, given the controversies that have surrounded this woman.

When Nixon entered the police force as an eighteen-year-old, she was aware that she would have to fight for promotion. She had to battle not only male attitudes, but also a cadre of senior women whom she calls ‘the dragons’, who could be as hostile as the men. Nixon’s earliest official confrontation with these hierarchies was as president of the women’s branch of the Police Association – at the age of twenty-one.

It was at Harvard University on a Harkness Foundation Fellowship that Nixon formulated the principles of policing in society that would become the benchmark for the rest of her career. The lessons she learnt there would determine the way she responded during the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria and how she would conduct herself in the subsequent royal commission.

In those two formative years at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Nixon rubbed shoulders with various members of the Kennedy family and with luminaries such as Henry Kissinger. As a research assistant in a project for the National Institute of Justice, she met Lee Brown, the first black police chief of Houston, and Daryl Gates, head of the Los Angeles Police Department, both advocates of community policing models.

Nixon returned to a New South Wales police force under the leadership of legendary commissioner John Avery, a mentor and close friend, who was determined to rid the force of corruption and to drag it into the modern world. The Wood Royal Commission of the late 1990s exposed endemic police corruption in New South Wales, but convinced Nixon that royal commissions often ‘failed to achieve what they ought … on very serious matters, [and] stole … attention from the real issues’.

When Nixon moved to Victoria as chief commissioner in 2001, she knew that some police in that state were not innocent of institutional corruption; they were just lucky not to have been exposed. Events proved her right. In the eight years leading up to Black Saturday, various inquiries into police conduct revealed that some Victorian police were among the largest drug dealers in that state. A sanctioned ‘sting’ had growninto its own shady enterprise. Assistant Commissioner Noel Ashby would be forced to resign, and Nixon’s ‘trusted’ media adviser Stephen Linnell would be exposed as the source of leaks to Ashby and Paul Mullett, secretary of the Police Association Victoria. The turf war among various crime families embroiled other members of the Victorian police.

Nixon had no time for old-style policing, where crooks and detectives consorted to more or less keep the peace. Her stated goal, the reason why she was employed by the Victorian government, was to change that culture. In doing so she collected a raft of enemies.

Much has been made of a military model of command that Nixon should have followed on Black Saturday. This model supposes that, as the state was engulfed by fires equivalent to fifteen hundred of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima, one person, a generalissima, would be in charge – to do, well, what exactly?

As the world lurched into the age of terror after 9/11, Victoria had considered the issue of emergency management. On Nixon’s watch, two assistant commissioners were delegated to oversee this task. According to the philosophy of policing that Nixon imbibed at Harvard, on Black Saturday: ‘I had an expectation [that] I would be kept apprised of the situation and would participate in various briefings to satisfy myself that responses were appropriate, but would not otherwise intervene …’ This model is in fact closer to the modern military one, where the response is decentralised.

Deputy Commissioner Kieran Walshe and Assistant Commissioner Steve Fontana were in charge of the operational response on Black Saturday. They were the experts, the ones with the specialist knowledge. The person who would be perceived by the public to lead the overall response was Chief Commissioner Nixon.

On Black Saturday, Christine Nixon kept a hair appointment, met with her co-writer Jo Chandler, and went out to dinner, while the toll of lives lost and communities destroyed went on rising. Nixon did spend a number of hours at the Emergency Response Centre before going out to dinner; she believed that events were being handled as well as they could be. Later she was accused of having her mobile phone turned off, but this she categorically denies.

Nixon’s actions on Black Saturday are inexplicable, uncharacteristic even, given that she was such a highly effective and visible presence during the recovery and reconstruction effort after the fires. There is a profound disconnect between what Nixon perceived her role to be on Black Saturday and the role that Victorians expected, and demonstrably needed, her to play.

One of the personalities who emerged during the course of the Bushfires Royal Commission was Rachel Doyle SC, whom Nixon describes as ‘an up-and-coming barrister with a reputation for hard work, forensic questioning, a sharp tongue and quick wit ... star material’. To Nixon’s consternation during the commission hearings, the young barrister expressed ‘a palpable impatience with explanations that tried to communicate the broader management structures or systems underpinning the response’. Instead, Doyle, questioning Nixon on two separate appearances before the commission, concentrated on what Nixon had done on Black Saturday, and why she had done it. During the first of these appearances, Nixon – to her detriment – replied ‘No’ to the direct question, ‘Did you need to be somewhere that evening?’

Doyle thus exposed the heart of the disconnect in Nixon’s leadership style: the veritable gulf between Nixon’s perception of her role on Black Saturday and the public’s (and, ultimately, the royal commission’s) expectation of that role. Ms Doyle grasped something that Nixon did not seem to understand when she left the control centre on that catastrophic night.

We live in uncertain times. The perceived indifference of the British royal family to the death of Princess Diana in 1997 nearly brought the British monarchy undone. Shooting massacres in the Netherlands and Norway this year have seen monarchs and prime ministers in those countries start tweeting to the public as soon as practicable, to allay fears and convey a particular message. Social media has the ability to communicate, polarise, and galvanise faster than any broadcast or broadsheet can. We live in an age in which society demands instant and constant access to its leaders, and expects a visible presence from authorities.

Nixon was an important agent of change in policing methods, and hopes that her actions on Black Saturday will not overshadow the achievements of the rest of her career. She adds, ‘Perhaps this is a vain hope.’

Comments powered by CComment