Society

The traveller, as V.S. Naipaul describes that role in A Turn in the South (1989), 'is a man defining himself against a foreign background'. Over the past forty years, Paul Theroux has built his career writing books, nearly fifty novels and travelogues, to become an exemplar of that definition. He seeks always to go farther and deeper, often journeying, to b ...

In 1971, the Boston Women's Health Collective published Our Bodies, Ourselves, which became an international phenomenon and was translated into twenty-nine languages. For second wave feminists, taking control of their lives and their bodies was a basic principle. The book provided information related to sexuality, birth control, abortion, pregnancy and chil ...

The Economist’s foreign correspondent John Hooper turns to a quintessentially English theme: Italians. Italians seem to be a sort of recurring obsession, a presence that periodically intrudes into the English imaginary. The cultural construction of Italy is a particularly sensitive and timely topic in the context of debates about the future of Europe. The a ...

To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism and the Urge to Fix Problems That Don't Exist by Evgeny Morozov

What are the implications of the ever-accelerating revolution in information communication technology on our lives? Is the Internet a force for good, for increased freedom and democracy? Or are we so in thrall to the prophets of Silicon Valley that we have lost sight of the perils that lie in ‘big data’, the extension of algorithms and quantification into every ...

When Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch was published in 1970, it created a sensation. Within six months, it had almost sold out its second print run and had been translated into eight languages. Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, the influence of which critics see in Greer’s book, had come out in France in 1949. The Feminine Mystique, b ...

Dear Life: On Caring for the elderly (Quarterly Essay 57) by Karen Hitchcock

In her long-form essay Dear Life, columnist and fiction writer Karen Hitchcock considers how we in Australia treat the elderly and dying. To the task she brings her formidable skills as a writer and her experience at the coalface, working as a staff physician in a Melbourne public hospital. The result is a sensitive, rigorous, and moving account that ex ...

The Rich: From slaves to super-yachts, a 2,000-year history by John Kampfner

Just how different are the rich from everyone else? F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in a 1926 short story that they are ‘soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves.’

... (read more)Russell Brand made headlines when he revealed in an animated interview with Jeremy Paxman that he had never voted. Fresh from guest-editing an issue of New Statesman, Brand had issued a call to overthrow the system responsible for the income disparities and environmental degradation in the world today – but refused, or was unable, to explain how this would happen.

... (read more)Northern Lights: The positive policy example of Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Norway by Andrew Scott

As Andrew Scott points out, Australians have a limited and very clichéd knowledge of the Nordic countries. Recently, we have come to appreciate Scandinavia for its bleak police dramas, of which The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is probably the best known. For the right, Scandinavia has long represented socialist excess, which merges with vague notions of unlimited sexuality. The reality is that Sweden, at least, has adopted some laws around sex work and sex venues which are far more stringent than those in Australia. For the left, the Scandinavian nations have represented the hope of a liberal democratic egalitarianism, with taxation and welfare policies that are far more successful than ours.

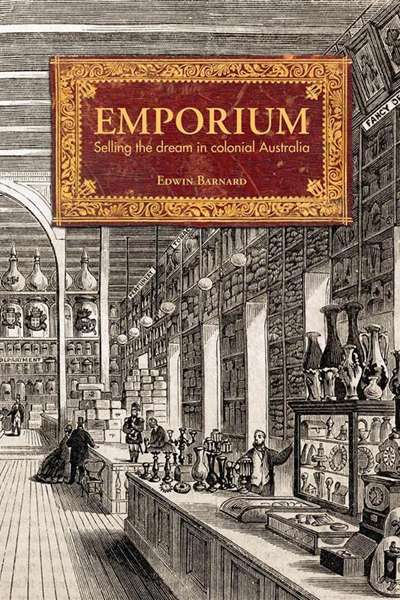

... (read more)Emporium: Selling the dream in colonial Australia by Edwin Barnard

Nowadays, with relentless advertising and a seemingly endless number of choices to confuse our every purchase, often only a click away from gratification, it might be tempting to imagine a time when things were simplerand retailing less pressured and more genteel. However, one would have to go a long way back in time to find an Australia without shops; indeed, to before 1790, when Sydney’s first recorded shop appeared. Indigenous Australians had traded commodities for thousands of years, but the European settlers brought thenotion of a cash transaction to the continent, even if, in the early days of settlement, a lack of liquidity led to bartering goods.

... (read more)