- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seductive Sydney

- Article Subtitle: The completion of Louis Nowra’s trilogy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I recently learned (was it from Martin Amis?) that ‘pulchritude’ is a synonym for ‘beauty’. How can such an ugly word be associated with beauty? I feel the same way about ‘Sydney’, named by Governor Phillip for the British Secretary of State who had suggested an Australian colony. An ugly word that is the name of a beautiful topography, a geologically complex and weathered arrangement of water and land, and more water and land, and a spread of fragmented populations that are in many cases discrete, so discrete that where a person lives and works in this city, defines and confines them. Infrastructure and transport must cope as best they can, and with as much money as government can muster.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

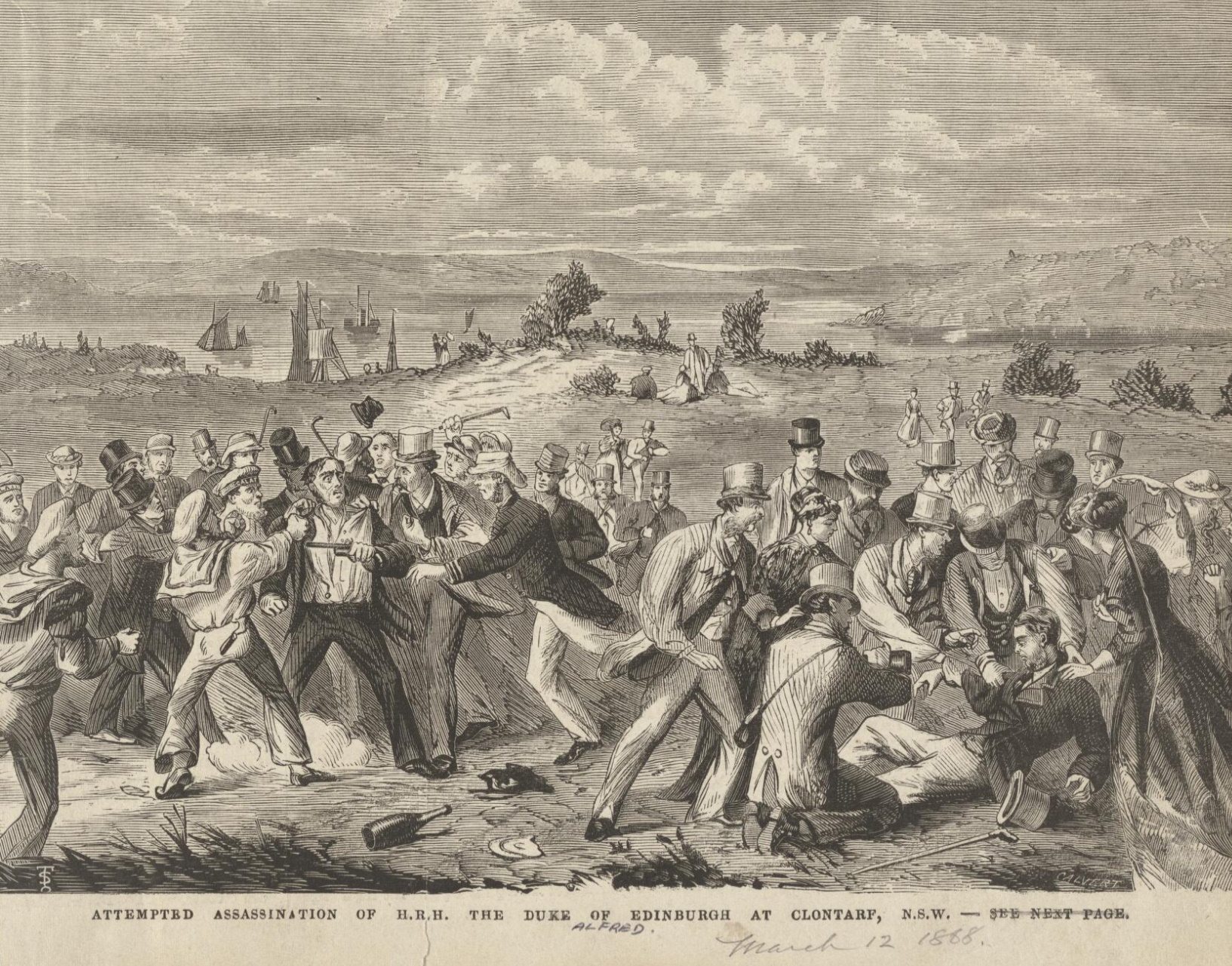

- Article Hero Image Caption: Attempted assassination of HRH the Duke of Edinburgh at Clontarf, NSW, wood engraving by Samuel Calvert (National Library of Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gay Bilson reviews 'Sydney: A biography' by Louis Nowra

- Book 1 Title: Sydney

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 498 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Some who left Melbourne for Sydney didn’t fall in love with it. An entry from Helen Garner’s 1987–95 diaries reads: ‘Thought of Sydney with indifference, even dislike.’ And another entry: ‘V keeps saying that Sydney is more “exciting” than Melbourne, that Melbourne is “suburban”.’ Garner still hankers for Melbourne.

I am another blow-in from Melbourne, staying for decades without succumbing to the seduction that Nowra finds nourishing, never quite feeling at home but proud to be there. I got to know the area close to Central Station when I was running the Bon Goût, the restaurant on Elizabeth Street that Germaine Greer denied was the epitome of café society in Sydney in the 1970s (Margaret Fink, mentioned by Nowra, had primed Greer towards contrarianism). I lived in Balmain for a short while, a variety of isolation. I also lived in the Cross and in Elizabeth Bay – even in Pymble for a short time, way off Nowra’s beaten track, while Berowra Waters Inn (Greater Sydney) was undergoing the second of Glenn Murcutt’s inspired renovations. I cared little for Sydney’s history in those twenty-eight years, except for rubbing impolitely against it by taking on Bennelong Restaurant at the Sydney Opera House.

Nowra’s Sydney is not a guidebook. For one thing it is too fat for a backpack. Nor is it a straightforward history. He writes that he has followed three themes: chronology; sandstone and water; spaces and places. This is to not mention people, yet people, historical and alive, give the book its most vivid passages. The many sections stand alone, as do the parts of Sydney he describes. He is following his own absorbing logic and his sense of mission in research. It is disappointing that there is no index, though there is a bibliography, as in the two earlier books in the trilogy.

A couple of examples of these chapters will serve to suggest the flavour of Nowra’s exploration. In ‘The Shame of Clontarf’ (yes, I’m one of those people Nowra suggests knows ‘nothing of Clontarf, “the hidden gem,” as the real estate agents call it’, in Middle Harbour). He is taken there by a friend, an artist, with whom he drinks at the Old Fitzroy Hotel in Woolloomooloo. The Old Fitzroy is Nowra’s omphalos. They explore Clontarf some 150 years after Henry O’Farrell attempted to assassinate Prince Alfred, the duke of Edinburgh, there. ‘I shall be hanged and the prince will live,’ said O’Farrell, and so it proved.

By 1882, Clontarf had become a ‘favourite place of recreation’, according to An Illustrated Guide to Sydney. In 1960, Bazil Thorne won the Opera House lottery, a fact indiscreetly reported in the papers. Thorne’s son was kidnapped for ransom, held in a house in Clontarf and then found dead in Seaforth, the next suburb along. The identification of two species of cypresses, needles of which were found on the blanket that wrapped the boy, were then recognised by a Clontarf postman as those growing on the property of Stephen Bradley, who was sent to prison for life. Clontarf, Nowra writes, now ‘radiates a self-satisfied Anglo gentility’. I’m guessing Nowra and his friend repaired to the Old Fitzroy to mull things over.

Another example: the architect Harry Seidler, defamed for his Blues Point Tower, gets an angry drubbing from Nowra: ‘With his bespoke suits, colourful bowties, and the cocky strut of a short arse, he imposed himself on Sydney.’ Seidler viewed the Queen Victoria Building as a monstrosity and wanted it pulled down, but – and surely to Seidler’s credit – admired Francis Greenway’s early nineteenth-century buildings. Nowra mentions the defamation case brought by Seidler against the cartoonist Patrick Cook in 1982. Cook had ridiculed Blues Point Tower as ‘a real offence against the harbour’. Cook won. Seidler fumed. But Seidler’s 1967 ‘Australia Square’ skyscraper was mostly lauded. The forty-three-storey Horizon building in Darlinghurst defied height restrictions, and, writes Nowra, is ‘a glaring example of a modern architect’s callous disregard for hoi polloi’. I admit to admiring the design of the Horizon but acknowledge that it is architecturally incongruous, socially discourteous.

Chronologically, from the fascinating story of the disappearance of the Tank Stream, once used by the Gadigal people for fresh water and food, through the Fairfax and Packer newspaper dynasties, the deeply moving photographs of William Yang, and so many other people and stories, Nowra is back in the Cross and Darlinghurst, celebrating the Bayswater Brasserie (an English food critic once told me he judged a restaurant by its loos and gave it a thumbs-up) and the Tropicana Café (where every week for years in the 1980s and 1990s I would pick up staff and their coffees to drive them to Berowra Waters Inn for three days of hard work, and where I had said to Matthew Condon, of The Sydney Morning Herald, ‘It’s only a restaurant, for god’s sake’). Readers might deem contemporary and near-contemporary stories puny in the face of the gravitas of historical fact and interpretation, but Nowra doesn’t.

One of his three epigraphs is from Paul Keating: ‘If you don’t live in Sydney, you’re camping out.’ Disparaging, élitist, and clever, it’s not a bad summation of Sydney’s id, super-ego, and ego.

Comments powered by CComment