- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Stories as currency

- Article Subtitle: History that feels very human

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

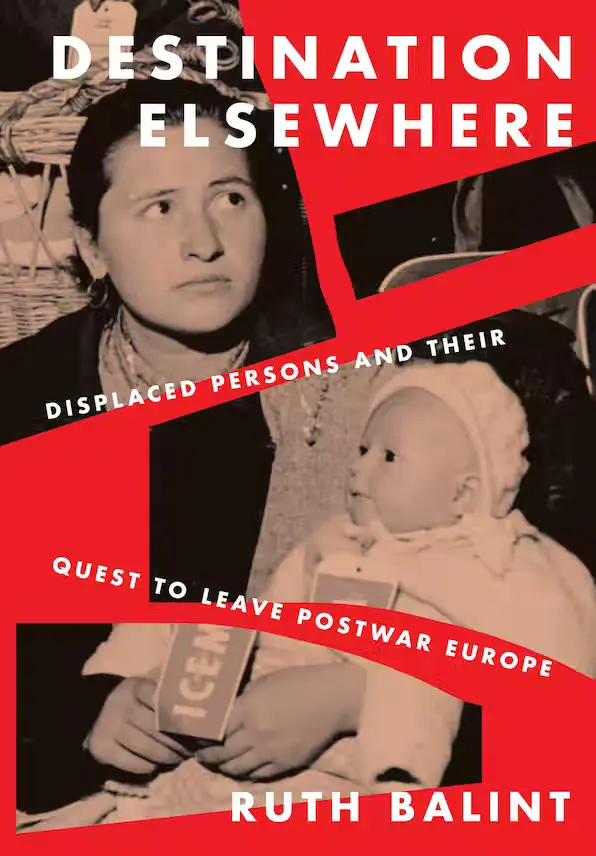

We often talk about refugees in terms of crisis: ‘unprecedented’ floods of thousands, waves of humanity displaced and now knocking at the door somewhere else. The scale can indeed be staggering. World War II displaced perhaps two hundred million people (one in every ten), worldwide. Figures like this are almost paralysing. How to solve a crisis of this scale, let alone attend to any one refugee’s needs? The experiences of ordinary people, the personal dimensions, are often lost. How do you find the individual in those millions? This is what Ruth Balint does so deftly in Destination Elsewhere: conveys the immense scale of the postwar refugee crisis, but also sketches faces, personalities, and the triumphs, hardships, and failings of individuals. It is a history that feels very human.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ebony Nilsson reviews 'Destination Elsewhere: Displaced persons and their quest to leave postwar Europe' by Ruth Balint

- Book 1 Title: Destination Elsewhere

- Book 1 Subtitle: Displaced persons and their quest to leave postwar Europe

- Book 1 Biblio: Cornell University Press, US$39 hb, 203 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Personal stories were a form of currency in Europe’s refugee camps. DPs had some degree of control over their postwar trajectory if they could successfully narrate their own lives. The ‘right’ answers to the IRO’s interview questions, which afforded refugee status and the opportunity at a new life elsewhere, circulated widely through the DP camps by that most reliable of networks: the rumour mill. The IRO’s Review Board, where DPs could appeal the decisions made about their futures, is a crucial backdrop in Balint’s book. There, we meet individuals like Vjekoslav M., captured by the British as a prisoner of war despite having been a civilian engine repairman, forced at gunpoint by German soldiers to drive trucks of food into Slovenia. He narrated this experience to the Board (with the help of a sympathetic official), arguing that he had not willingly assisted the enemy and was himself a victim of persecution. But the DPs knew that the most effective way to undermine a compatriot was via their narrative; denunciation became a ‘new indoor sport’ as they sat in camps, ‘waiting, bickering and worrying about their futures’.

The cards were stacked against some of those working to secure their futures. Single women found that IRO officers were more suspicious of their stories, and were less likely to receive refugee status than their male counterparts. Single mothers had a particularly difficult time. Relief agencies worried that war had damaged women’s ‘maternal and feminine “instincts”’, leaving them unable to perform their duties. The family was the primary organisational unit for the postwar world: relief workers tried to retrain women in homemaking and domestic skills, and placed children previously kidnapped by the Nazis with foster families in the United States and Canada, rather than returning them to parents in the Eastern Bloc. Balint’s discovery of parents pressured into leaving behind children deemed mentally or physically ‘defective’, to meet the exacting standards of the resettlement countries’ selection officials, makes for particularly difficult reading – and repudiates the notion that the world lost its appetite for eugenics after the horrors of the Holocaust. As Balint writes, ‘Clearly not all families were entitled to the new world.’

Australia was particularly culpable when it came to exacting standards and ‘ideal types’ – particularly racial types – of refugees. Balint tells a global story, but as the book moves from relief workers and camps into resettlement, Australia becomes its focus. Despite Australian officials’ precise requirements, relatively few DPs actually wanted to go there. Balint describes how an Australian filmmaker sent to Germany wrote home that, to many DPs, ‘Australia is the gambler’s shot when attempts to get to America have failed.’ Australian authorities worked hard to convince refugees to choose them – a seemingly strange attitude now, when Australia conveys hostile deterrence to asylum seekers.

Many DPs who did choose Australia did so in an attempt to disappear. For some this was an opportunity to escape the Soviet Union or the trauma of the Holocaust. Others sought to leave behind spouses and children, starting afresh elsewhere. More disturbingly, it also became a way for Nazi officers and concentration camp guards to flee, ‘melting away into the populations on the move’. Australia’s policy of assimilation, which demanded that migrants leave their pasts behind and quietly blend in to Anglo-Australia, is now commonly understood as oppressive – and with good reason. But as Balint shows, there is also ‘the very real agency of some migrants who might have used, and even embraced, this opportunity’.

Balint’s refugees are, as she writes in the book’s conclusion, ‘neither heroic nor helpless’. Destination Elsewhere presents stories of suffering, survival, perseverance, and achievement, but it is not hagiographic, nor does it shy away from the complex and unsavoury realities of denunciation and even Nazi collaboration. Her DPs number in the millions, but she paints a range of faces, experiences, and stories. Balint presents thorough research with vivid prose – a portrait of the complex, human face of a refugee crisis and the postwar world tasked with solving it.

Comments powered by CComment