- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Looking for them

- Article Subtitle: The legacy of Christine de Pizan

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

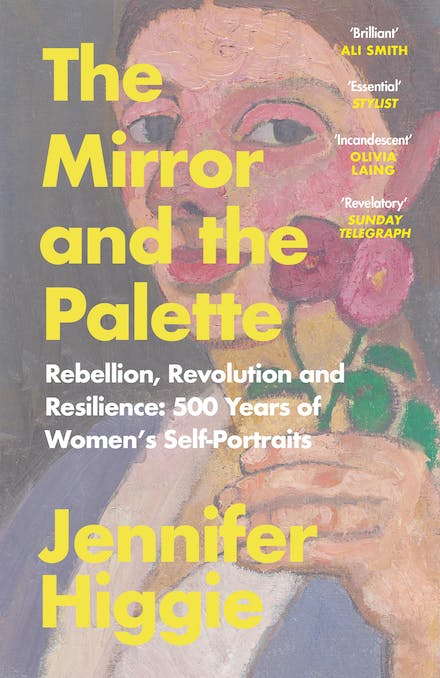

I dare say Christine de Pizan (1364–c.1430) would be surprised by her current celebrity: six centuries is a long wait. Now the name of this foundational European feminist writer, working in fifteenth century Paris, seems to crop up everywhere. She was invoked in Zanny Begg’s 2017 video The City of Ladies, which is touring Australian galleries until early 2024, and now on the first page of Jennifer Higgie’s rollicking The Mirror and the Palette. In her medieval bestseller The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), de Pizan wrote: ‘Anyone who wanted could cite plentiful examples of exceptional women in the world today: it’s simply a matter of looking for them.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Julie Ewington reviews 'The Mirror and the Palette' by Jennifer Higgie

- Book 1 Title: The Mirror and the Palette

- Book 1 Subtitle: Rebellion, revolution and resilience: 500 years of women’s self-portraits

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $24.95 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The thematic groupings nearly always work, though I am baffled by the a-chronological appearance of Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–84) in a chapter on the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The best chapter, overall, is ‘Hallucination’, on the complex connections between the imaginary figure of ‘Woman’ and actual women artists in the Surrealist movement. Here, Leonora Carrington and Frida Kahlo are set in a convincing historical context, a setting that I often missed, despite Higgie’s spirited evocations of individual lives, such as the (almost contemporary) lives of Englishwoman Gwen John and French painter Suzanne Valadon.

The emphasis on the personal often leaves broader matters behind: I was looking for a more extensive account of the New Woman, for instance, and her emergence into professional life at the turn of the twentieth century. This context frames not only John but Bashkirtseff, the Finn Helene Schjerfbeck, Rita Angus, Preston, and others. Another question turns on the distinction between the general and the particular. I am restless with Higgie’s invocation of the artist as one subject, the one desiring ‘She’ invoked in the prologue, epilogue, and chapter openings, such as ‘Allegory’: ‘She doesn’t just paint; she is the embodiment of painting.’ This trope is too large (and simultaneously too constricting) to be helpful. All women, all artists, are, as they say, very different people.

This being so, it’s the details (the novelist’s eye?) that make The Mirror and the Palette. This well-packed portmanteau bursts at the seams with great stories: Degas’s letters in the 1890s encouraging Suzanne Valadon to keep painting, and in the 1980s Nora Heysen, who in 1938 became the first woman to win the Archibald Prize, drily saying that she prefers ‘comfortable obscurity’. Paula Modersohn-Becker’s short life and luminous naked self-portraits are highlighted with vignettes showing her seeking solace in married life in her garden, and failing: her painting could not wait. Higgie drives these narratives along at a fast clip, so much information bundled into the book that it reads well as a sort of guide, with the internet handy for excursions into online imagery or additional information.

The Mirror and the Palette is part of a contemporary plethora of publishing on women artists, and this paperback edition will reach far more readers than the pioneering studies of women’s self-portraits by feminists such as Frances Borzello. My local bookstore reports a great appetite for books about women artists: Phaidon’s doorstopper Great Women Painters (2022), with its 300 one-page entries, sits alongside Higgie’s intimate account, as well as the National Gallery of Australia’s Know My Name (2020), Anne Marsh’s huge anthology Doing Feminism (2021), and many recent monographs.

Finally, despite its enthusiasm, The Mirror and the Palette reminds us of the ambivalence at the core of feminist accounts of conventional easel painting. For this is a prehistory of the present, when painting was still the pre-eminent art of the Northern Hemisphere and its colonies. It isn’t now, certainly not for feminist artists: the great work of contemporary self-discovery was more frequently done through photography, as Higgie acknowledges, and, as Marsh argues so cogently, through video and performance. In any case, why does the book conclude with the great American Alice Neel, who died in 1984?

Today we do know what women artists want, and it’s not just working within established artistic conventions, or even conquering them. As the British art historian Griselda Pollock wrote, quoted in that Phaidon book, ‘As a woman I desire difference. I want to know about ways of seeing the world produced from situations I might recognize …’ These days, women work in multiple art forms: authorised, unconventional, unexpected, wildly innovative. ‘Mirrors’ do not require a matching palette.

Comments powered by CComment