- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A flawed hero

- Article Subtitle: Understanding the ‘real’ Matthew Flinders

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

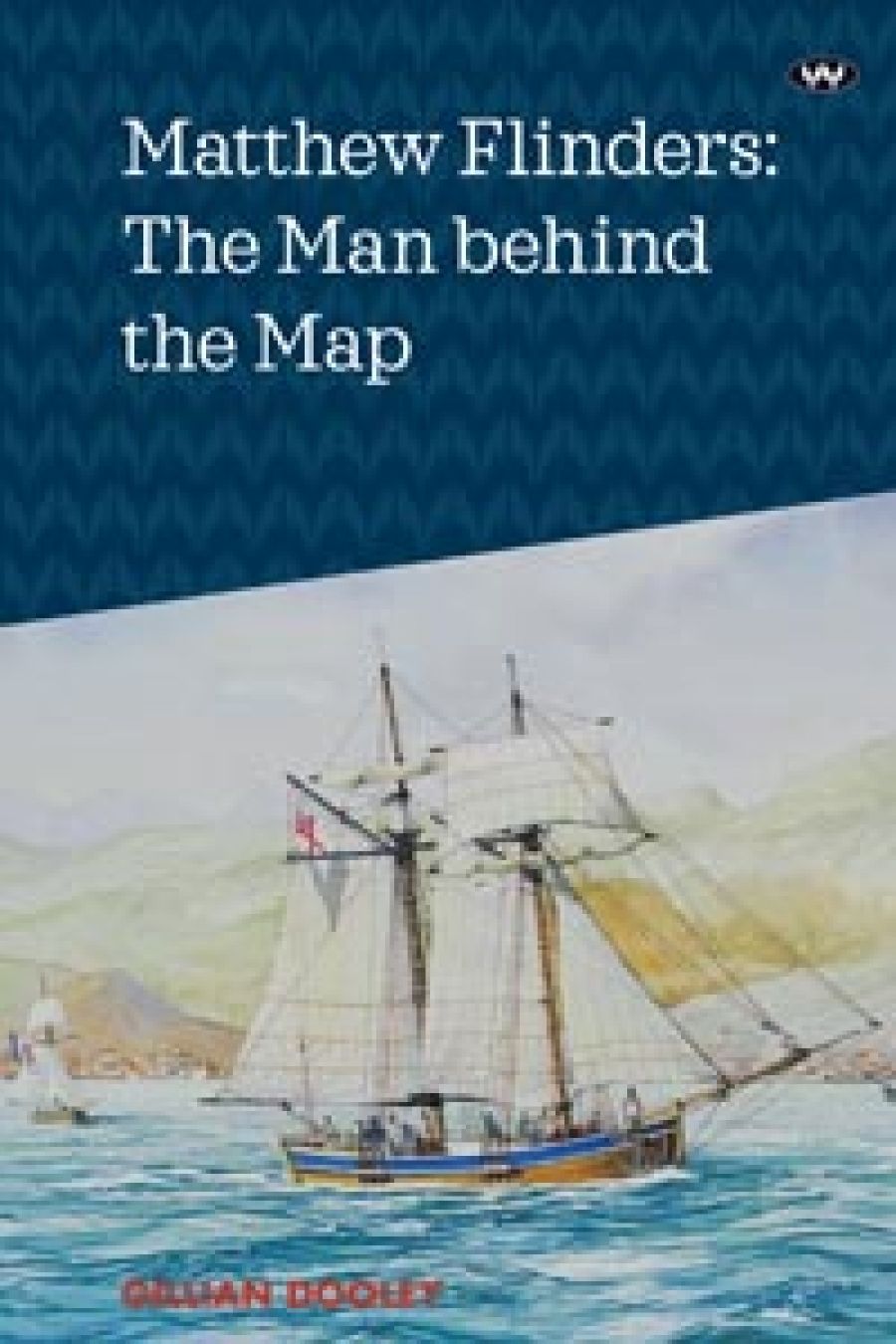

Few names are so ubiquitous in Australian culture or hold such a significant position in its history as that of Matthew Flinders. More than one hundred sites across Australia have been named in his honour, commemorating his accomplishments as a navigator, hydrographer, cartographer, and scientist. Among them are several statues featuring Flinders with Trim, his ever-faithful pet cat and companion, as well as numerous geographic landmarks, electoral districts, and a university.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Matthew Cuneen reviews 'Matthew Flinders: The man behind the map' by Gillian Dooley

- Book 1 Title: Matthew Flinders

- Book 1 Subtitle: The man behind the map

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $39.95 pb, 261 pp

Dooley structures her book not as a conventional, chronological biography, but as a series of essays edited from her previous talks, presentations, conference papers, and other research on Flinders. These are divided into five parts, organised thematically. The first focuses on his Private Journal, written during the last eleven years of his life. The following section considers his relationships with voyages and islands. Dooley then investigates his social networks for insights into his character and opinions, before embarking on a discussion of his foremost passions of reading, writing, and music, and concluding with ‘Occasional Pieces’, various contemporary Flinders-themed writings celebrating and considering his life. While this structure effectively foregrounds various aspects of his life, the disjointed narrative style may prove unsatisfying to readers unfamiliar with Flinders.

Guiding Dooley on her quest to better understand Flinders – son, brother, father, husband, friend – are his writings. Throughout, she presents revealing excerpts from his journal, the official account of his circumnavigation of Australia, A Voyage to Terra Australis (1814), and numerous letters to friends, family, patrons, and other personal connections. These are supplemented by the writings of figures who featured prominently in his life.

Dooley has spent decades writing on Flinders; she is driven by an enthusiasm readily conveyed in her prose. With deep empathy and vivid imagination, she humanises a man whose historical distance and celebrity status would otherwise make him forbidding to a modern reader. Excerpts from his works allow us a front-seat view of his innermost thoughts and feelings – his humour, ambition, love, depression, and anguish. Dooley’s Flinders is not an arrogant man but one who valued his honour like most British naval officers of the period. Hardly religious, he possessed a scientific curiosity and rationality that were characteristic of the Enlightenment as well as a love of culture congruent with the era’s romanticism.

Published by a non-academic press for a general audience, the book partially eschews academic scaffolding and conventions. In some ways, this absence is detrimental to Dooley’s project, which would have benefited from some basic source analysis early in the text. Since firsthand descriptions of Flinders are scant, she relies on his writings to deduce his innermost thoughts and feelings. However, to understand such sources we need to know why they were written and for whom, what conventions such texts follow, and the nuances of the genres they belong to. We also need to become acquainted with the semantics of the period. This is not to say that Dooley lacks a grasp of such matters, but simply that the reader is sometimes left pondering the rationale for her interpretations.

The tone and style of Dooley’s writing vary between chapters, reflecting their different intended audiences. This makes for a mildly jarring reading experience. In the absence of a chronological structure, she is made to repeat important information that contextualises key moments in Flinders’ life. Likewise, the repetition of quotations from his writings on occasion burdens the text’s flow and becomes monotonous. Nonetheless, Dooley’s book is an engaging read, written in an easily accessible style that allows Flinders’ personality to shine through.

Today, the legacies of many traditional Australian heroes – including, notoriously, James Cook – face mounting public scrutiny and condemnation as their role in colonisation and dispossession proves increasingly repugnant to some modern sensibilities. Dooley acknowledges Flinders’ complicity in the British Empire’s colonisation of Australia and indeed his violent interactions with First Nations peoples. While not absolving him of wrongdoing or treating him as a saint, she encourages us to see Flinders as a man of his times, extraordinary and flawed but far from irredeemable.

Dooley’s work renews Flinders as a figure who possessed many of the virtues still valued in Australia – hard work, affection, and courage, to name a few – and justifies his continuing status in settler historical consciousness as worthy of admiration. Her evocative reconstruction of Flinders the man will go a long way to making that possible.

Comments powered by CComment