- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mapping the grey zone

- Article Subtitle: An essayist comfortable with uncertainty

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Maps are central to Kim Mahood’s practice as a writer, artist, and intercultural collaborator. She began making them in the wake of her father’s death in a helicopter mustering accident thirty years ago. This tragic event compelled her to make a pilgrimage to the country where she spent her late childhood and teenage years living on Mongrel Downs cattle station in the Tanami Desert. This journey became the subject of her award-winning memoir, Craft for a Dry Lake (2001). This journey set in motion a renewed relationship with the place that has seen her return to the Tanami annually for more than twenty years. The relationships that developed during this period resulted in Mahood’s longstanding preoccupation with maps and mapmaking developing into collaborative mapping projects with Walmajarri and Jaru peoples, the contours of which she traces in her second book Position Doubtful: Mapping landscapes and memories (2016).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

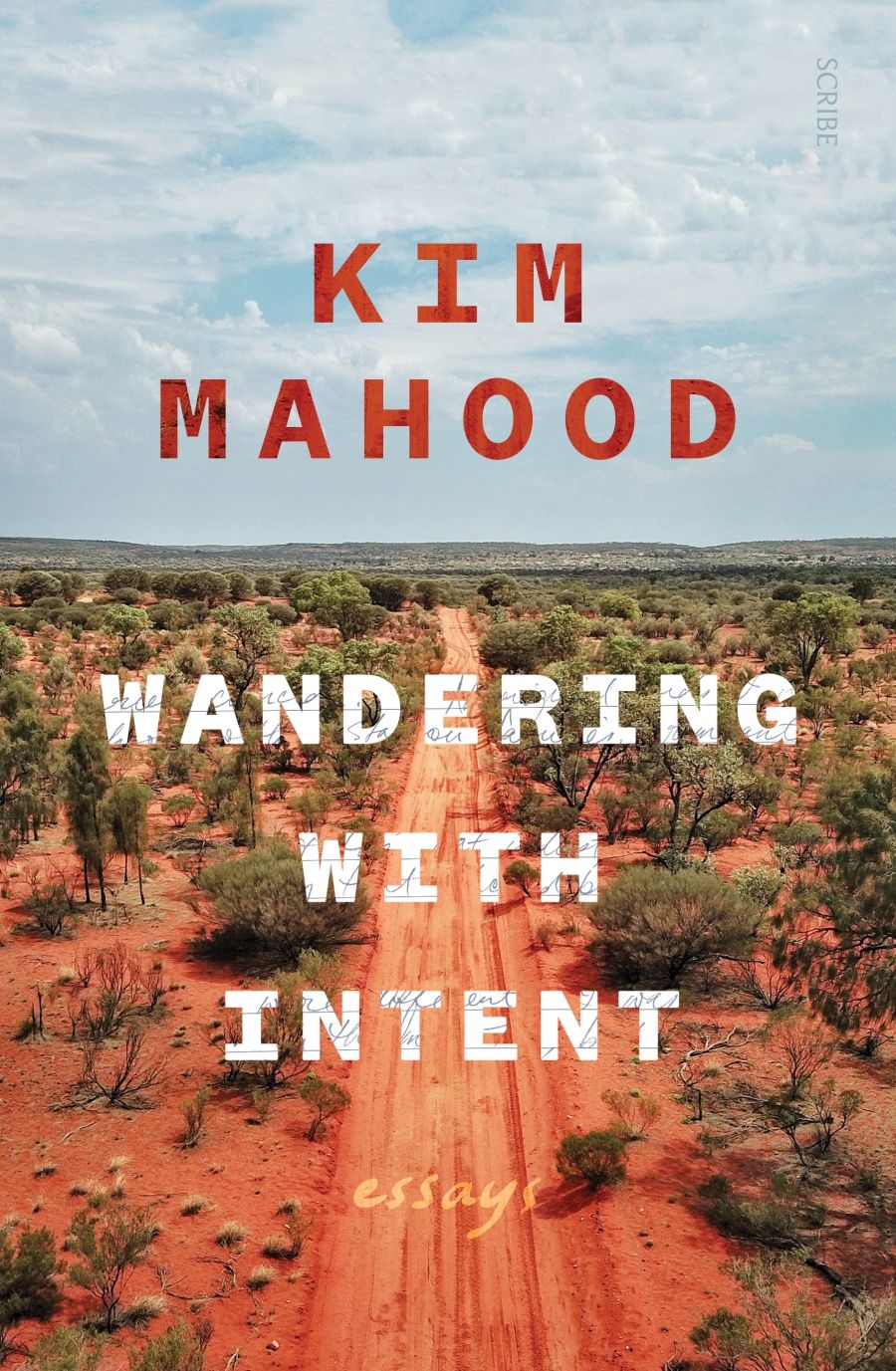

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Shannyn Palmer reviews 'Wandering with Intent: Essays' by Kim Mahood

- Book 1 Title: Wandering With Intent

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 270 pp

Mahood, an essayist who is comfortable with uncertainty, acknowledges her flaws and contradictions, and those of the people she writes about. She pre-empts criticism of her being a white woman writing so frankly about First Nations peoples, and wonders in the preface to the collection ‘what the implications of cancel culture and identity politics might be’ for her. In revisiting her earlier essays, Mahood flags that she has not edited out ‘what might now cause offence and attract criticism’ because to do so would be disingenuous. Some readers might bristle at Mahood’s candid descriptions of First Nations lives, experiences, and knowledges, or find her use of terms like ‘white slavery’ jarring, but for Mahood these moments are an honest reflection of an imperfect attempt to ‘understand and communicate’ the fraught zone between Black and white worlds that she has occupied for much of her life.

In ‘“Kardiya are like Toyotas”: White Workers on Australia’s Cultural Frontiers’, Mahood constructs a withering critique of remote community dynamics, where more often than not the ‘white population … is disproportionately influential while being unequipped, unprepared, or unsuitable for the work it does’. First published in Griffith Review in 2012, the essay went viral when it was circulated widely among white settlers (myself included) who were living and working in remote desert communities. Reading Mahood’s observations in the wake of the 2019 shooting of Kumanjayi Walker by policeman Zachary Rolfe in Yuendumu, I was struck by the essay’s continued relevance ten years after it was published. In shining a light on the ‘sociopaths, the self-righteous, the bleeding hearts, and the morally ambiguous’ who ‘manipulate … injustice as a means of maintaining power’, Mahood lays bare the world that Rolfe described in text messages as the ‘wild west’ – a place where conditions are ripe for white men and women to see their positions of power as an opportunity to play out their ‘cowboy’ fantasies in a place ‘with no rules’.

In essays such as ‘The Seething Landscape’ and ‘The Man in the Log’, Mahood explores examples of collaboration that ‘run counter’ to the trope of dysfunction depicted in ‘“Kardiya are like Toyotas”’. The improvised space between black and white worlds has been central to Mahood’s life, and ways of working in the overlap between First Nations and settler Australia is a key thread that runs throughout this collection. In ‘From Position Doubtful to Ground Truthing’, she traces the trajectory of her own co-mapping projects with First Nations peoples over twenty years, and in doing so traces the development of a philosophy and methodology of collaborative practice that is ‘open-ended, responsive to the priorities of the people involved, and only provisionally driven by outcomes’.

There is a deep sense of searching in this collection; of wandering with the intent of trying to understand more deeply a place that Mahood describes as ‘central, necessary, cross-wired into my neural circuits and the geography of my body’. In this sense, Mahood’s collection diverges from the lineage of Australian desert writing that has been overwhelmingly dominated by white men such as Ernest Giles, Baldwin Spencer, Frank Gillen, J.W. Gregory, C.T. Madigan, T.G.H. Strehlow, and, more recently, Nicolas Rothwell and Mark McKenna, to name just a few. Although Mahood is mapping the country in her attempt to understand it, she is not trying to conquer the country, or to know it in a Western epistemological sense. Rather, she resists certainty and instead emphasises listening in order to understand the many truths and meanings that reside in places. Mahood’s work is an important contribution to a growing body of writing about the inland that is being shaped by women’s perspectives, both black and white, who are ‘less oppressed by the existential void, less impressed by the explorer narratives’ and bring a ‘very different sensibility, and one whose time has come’.

While Mahood’s probing essays offer valuable insights into the complex intersections between First Nations and settler Australia, some readers may feel that the time has come for a deeper engagement with the racist, settler–colonial structures that shape the world that is central to her writing. Yet, Mahood writes that her experiences in the grey zone have produced in her ‘a kind of moral inertia, which manifests as an acceptance of the way things are, rather than as a desire to fix or change them’, which she confesses can ‘leech away the energy to feel strongly about things that warrant strong feelings’.

Comments powered by CComment