- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Custom Article Title: Three new short story collections

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Much in little

- Article Subtitle: Three new short story collections

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is a short short story? More specifically, how short is it (or how long)? The most famous tiny example is attributed to Ernest Hemingway: ‘For sale: baby shoes, never worn.’ Whether he wrote this or not, it represents the gold standard in suggesting much in little. Like poetry, microstories or flash fictions allow no formal wobbling as authors tread a perilous tightrope between banality and inspired ingenuity.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Debra Adelaide reviews 'Miniatures' by Susan Midalia, 'Bloodrust' by Julia Prendergast and 'Women I Know' by Katerina Gibson

Despite (or maybe because of) this, identifying specific pieces from Miniatures for attention is problematic. It is possible to read the entire collection in one sitting, and while much of my hour was spent smiling, it is hard to ignore the implications of this. Is this mere diversionary reading? So many stories, so much hard work, imagination, and intelligence, to be consumed so quickly? All these little gems. But is describing the stories as ‘gems’ damning the collection with faint praise?

I don’t want to do that, so I shall mention some: ‘In the Park’ features technology as the enemy of human communication, with an unexpected bittersweet twist; ‘Subversion’ will appeal to punctuation Nazis with guerrilla tendencies; while ‘The Session’ is another of several literary stories, this time for language pedants. ‘For Sale’ describes an argument between a married couple, over said Hemingway story, in which she snaps at him that he is stupid and insensitive and she doesn’t know why she married him, while he replies, ‘Now, that’s a story.’ Despite this, he does not get the final word, or rather six words.

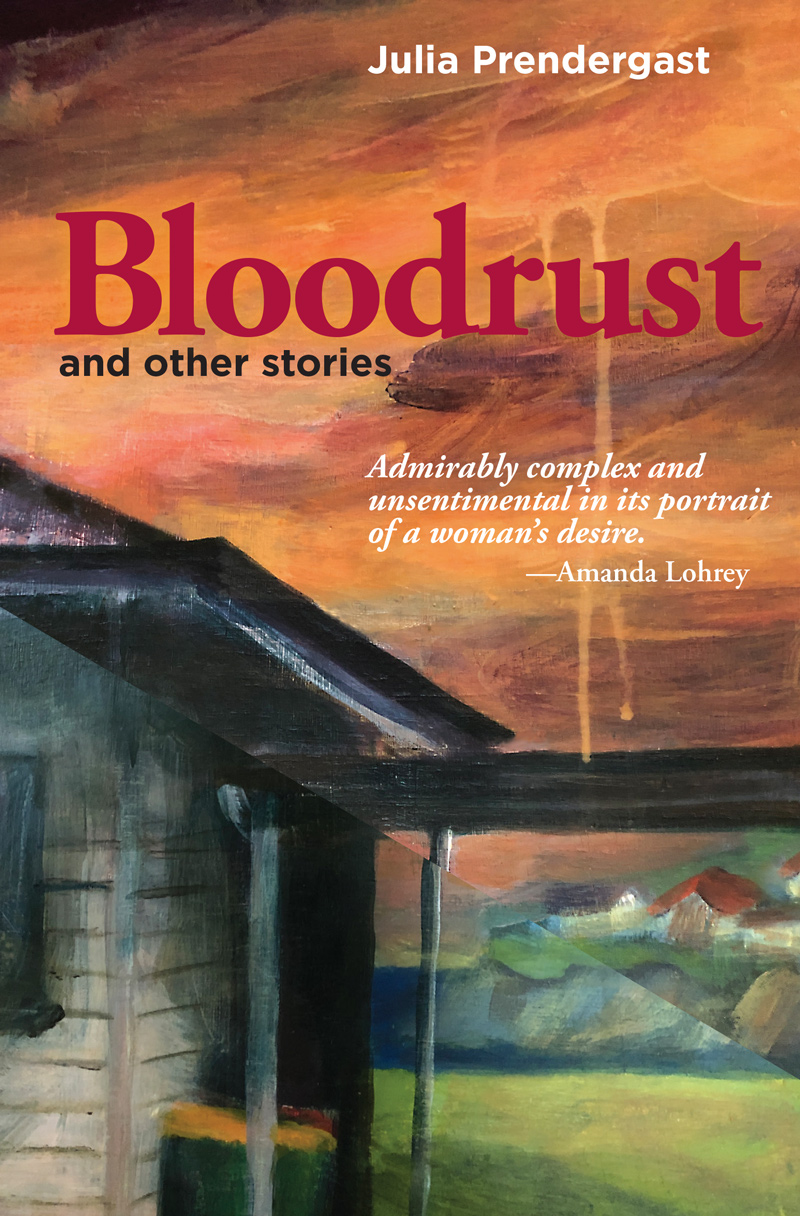

Bloodrust by Julia Prendergast

Bloodrust by Julia Prendergast

Spineless Wonders, $24.99 pb, 160 pp

The whole collection may resist lasting effect, but the skill and economy in Miniatures are admirable. By contrast, any concerns about Prendergast’s Bloodrust (the status of its microfictions aside) assuredly have nothing to do with it being delightful or diversionary. This is a rough and tough collection, but this feels intentional. You also get the feeling that the book has not been permitted to stand on its own feet, judging by the huge number of endorsements from other writers. This is a pet hate of mine: prelims stuffed with praise only compromise what should be a virgin reading of a book. Impatience and cynicism are not the best attitudes to bring to an opening page. Fortunately, the first story here copes.

In ‘Contrapuntal’, a mother having a birthday dinner with her grown-up family gradually expresses frustration and resentment as she contemplates the whole ‘fuckwittery of mothering’, until finally barking an order that echoes her own mother. The brittle opinions and raw feelings here are reflected in language that is choppy, heavily reliant on punctuation, filled with hyphenated hybrids (‘love-hated’, ‘pain-eyes’, ‘womb-poisoning’), accumulated adjectives, and sentence fragments. The effect is one of barely contained and mostly negative emotions, and this continues across the entire collection, where pain and violence, either actual or suppressed, dominate. The characters are destructive, angry, wound-up, vulnerable, confronting. The title story, one of the longest, features a young woman negotiating several relationships in succession, while obliged to confront nature’s powers both within and without her own body. The story’s ambition is admirable but it is also overly busy, and the lack of intimacy between reader and character is problematic.

‘Like Clay’, however, is powerful – for me the best in the collection. Here a teenage boy has helped his mother birth his baby sister at home. With an emotionally absent father and other chips on his shoulders, Clay simmers with the menacing tension that many of the other characters, especially male ones, in Bloodrust have, but here it is funnelled into the right places, and the result is unexpected and wonderful.

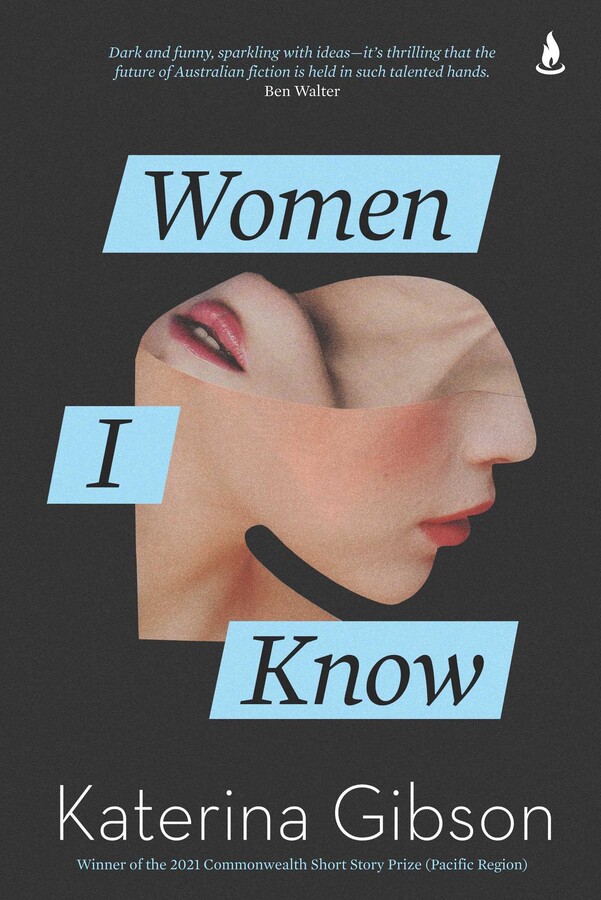

Women I Know by Katerina Gibson

Women I Know by Katerina Gibson

Scribner, $29.99 pb, 246 pp

If the stories in Bloodrust mostly deliver raw emotional punches, those in Katerina Gibson’s Women I Know (Scribner, $29.99 pb, 246 pp) demonstrate an intellectual and imaginative power in their fearless probing into corners of the human world we didn’t even think existed until now. The collection is Gibson’s first and the stakes are impressively high, the ambitions mostly fulfilled. In its acid, world-weary voice and subtle progression, the title story could almost belong to Dorothy Parker, though Parker surely is not one of Gibson’s influences: George Saunders, Joy Williams, and Lorrie Moore are more likely contenders. In ‘Women I Know’, an older woman is ostensibly conversing with her granddaughter, trying to come to terms with the public disgrace of her own son; few details are provided but the granddaughter’s silence and her decision to cut her hair are poignant indications of the extent of his crimes, and by implication the inheritance of shame.

Good as this story is, there are better ones. As the maybe-Hemingway microstory proves, it is not what is stated that counts, but what is omitted, and what a reader is empowered to envisage. Thus ‘Constellation in the Left Eye’ is a standout. A young refugee worker in a factory process line inserts eyeballs into lifelike dolls. Beyond that we learn very little, but the simple lucid voice of the narrator describing her work conveys a weight of context, and says much about the status of refugees, about class and working conditions, about culture and gender and power imbalances, about female vulnerability – all via omission; the restraint and creative control are such that this story remains long in the imagination despite it never explaining where or for what these dolls are used.

But longer stories also unfold with ease. ‘As the Nation Mourns’ is an intriguing account of an insomniac and thus confused marine researcher who is haunted by her recently dead and famous naturalist father, and who seems as vulnerable to exploitation as the rare species of fish she is determined to preserve. Deadpan acceptance of increasingly bizarre scenarios is common in this collection. In ‘Glitches in the Algorithm’, a woman’s curated online version of her life eventually supplants her real self, while in ‘Fertile Soil’ a series of odd coincidences leads a woman to discover she has a double, though that is far from the end of the story.

Interrogations of female experience prevail in the stories. ‘Intermission II: On the Mythology in the Room (Field Notes)’ is both a diversion in the form of a tour guide talking us through stereotypes of women and also a serious question about literary representation. ‘Schedule’ is a witty comment on the gendered nature of the corporate world and the perennial struggle between the working and family life.

Despite its main theme, the project of Women I Know does not involve valorising, defending, or explaining women. Indeed, the irony rippling through stories like ‘Schedule’ reveals an author prepared to question and disrupt everything. This is an assured collection, audacious, dark, comic, and full of surprises – it demands to be reread, several times.

Comments powered by CComment