- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

- Review Article: Yes

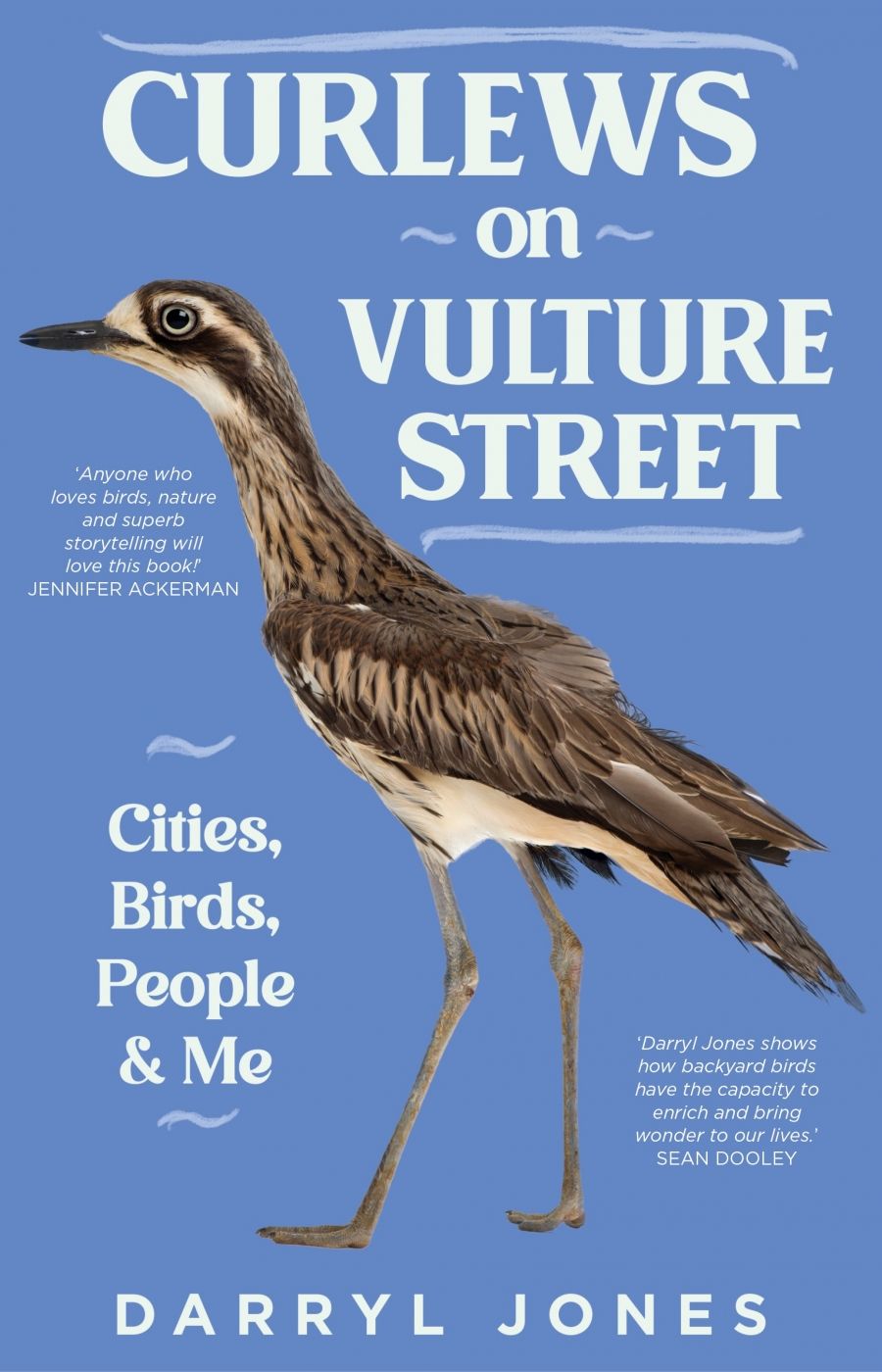

- Article Title: Feathered opportunists

- Article Subtitle: Darryl Jones’s quirky natural history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Within the Australian natural history genre, this book stands out: a quirky mix of autobiography, insights into the behaviour and adaptability of familiar Australian birds, and a fine example of the role of science-based enquiry to help solve human–wildlife problems. Darryl Jones, the author, is one of Australia’s most engaging and high-profile ornithologists. Although the tone of this book is decidedly non-academic, it is packed with information and insights.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter Menkhorst reviews 'Curlews on Vulture Street: Cities, birds, people and me' by Darryl Jones

- Book 1 Title: Curlews on Vulture Street

- Book 1 Subtitle: Cities, birds, people and me

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $32.99 pb, 322 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/curlews-on-vulture-street-darryl-jones/book/9781742237367.html

For me, Jones’s chapters highlight the fluidity of nature. There are few hard rules and a constant state of flux as species respond to changing conditions and as natural selection takes its unremitting course. The chapters reinforce my experiences in observing birds over many decades in suburban Melbourne. Here, the dominant bird community of the 1960s has been almost entirely replaced. Thus, House Sparrow, Common Starling, and White-plumed Honeyeater have all but disappeared, their places taken by larger, aggressive species including Rainbow Lorikeet, Noisy Miner, Little Wattlebird, Grey Butcherbird, and Pied Currawong. The Red Wattlebird, Common Blackbird, and Common Myna have remained throughout. Surprisingly, one small bird, the Brown Thornbill, has moved in, surviving where dense shrubbery provides cover from aggressors and predators. Several species formerly considered to be inland species have also moved in, notably Galah, Little Corella, and Crested Pigeon.

This brings me to an important point also emphasised by Jones: the new arrivals in suburban Australia are not predominantly refugees fleeing habitat destruction elsewhere and making do in poorer quality habitat in our cities and towns, as seems to be commonly believed. Rather, they are opportunists, mostly dispersing young, taking advantage of vacant ecological niches, for example by learning to use novel food, nesting sites, and roosting sites. This is natural selection in action and has likely resulted in an overall increase in the populations and security of those species. Such adaptation is an ongoing process that should be acknowledged and celebrated, while also catering for the less adaptable species in an extensive and well-managed system of conservation reserves where natural habitat is conserved.

A remarkable example of adaptation is the story of Rainbow Lorikeet roosting behaviour in suburban Brisbane. They actually prefer to roost in huge groups (up to 30,000 individuals!) under the brightest lights available, such as a huge car park at an all-night gambling venue, the benefit apparently being reduced risk of predation. This behaviour by a native bird species does not seem to have been reported in other Australian cities, although it brings to mind the noisy communal roosts of the introduced Common Myna in trees under streetlights in Melbourne.

The book provides intriguing insights into the behaviour of the Australian Magpie, one of our most recognisable and best-known birds. Australian Magpies are not ‘real’ magpies. They are large butcherbirds that feed terrestrially; true magpies occur across Eurasia and are members of the corvid family (crows and ravens). Our maggies have complex and fascinating social lives that vary widely. Some live as lifelong monogamous pairs, and the young are forced to disperse when almost a year old. Other pairs tolerate offspring remaining in the parental territory where they assist, to varying degrees, in the raising of future generations. Under this arrangement, some individuals are ‘helpers’ for most of their life and may never form a pair bond themselves. Of course, Australian Magpies are also feared for their swooping behaviour, which has resulted in serious facial injuries. Jones and his team have pioneered science-based research into this behaviour, and their learnings and recommendations are fascinating.

Jones is also intrigued by the habit of feeding wild birds in our home gardens, a practice that is entrenched in Britain, Europe, and North America, but that is less developed in Australia. Or at least that was Jones’s perception before they began to investigate. It seems that bird feeding is more common in Australia than is widely realised, but we tend to do it on the quiet and in an unstructured way. Why that is so is not understood, but my experience is that opposition to the garden feeding of birds arose from the Melbourne-based Bird Observers Club during the 1960s and 1970s, a reluctance that was based on a belief that it would lead to poor dietary outcomes and could spread disease. Jones correctly points out that those issues can be overcome by a public information campaign aimed at improving practices. Either way, Jones is an advocate, contending that the practice can be mutually beneficial to birds and humans.

This book is a fine example of communicating science to non-scientists. It provides useful insights into how scientists operate, for secondary and undergraduate students who may be considering postgraduate research. It is also an entertaining read.

Comments powered by CComment