- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

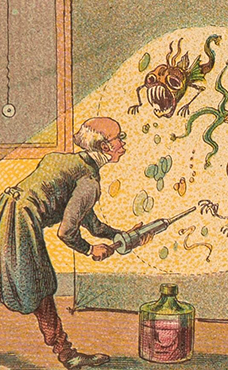

- Custom Article Title: Covid travellers: The struggle between historians and microbes

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Covid travellers

- Article Subtitle: The struggle between historians and microbes?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the middle of 2022 researchers at the Kirby Institute at the University of New South Wales announced that Covid-19 had infected more than half of Australia’s twenty-six million people. The number came not from polymerase chain reaction tests, nor from the results of rapid antigen home tests, but from the sampling of Australian blood banks. After all the tables, graphs, and pressers, the serosurvey demonstrated that the virus was everywhere among us and inside us, reconfiguring our bodies as well as our social and political worlds.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): James Dunk on the struggle between historians and microbes

Early in the pandemic there was, in fact, a real hunger for history. Many reached instinctively towards the past to understand the present. Some looked for precedent, solid ground, or lessons and assurances, while others looked for confirmation that these events were decidedly unprecedented. They reached out to historians – none more so, in Australia, than Peter Hobbins, a historian of medicine and technology at the Australian National Maritime Museum and a wonderfully clear communicator. In 2018 and 2019, Hobbins led a centenary project mapping how the 1919 pneumonic influenza pandemic had transformed Australian society. After Covid-19 appeared on the world stage, Hobbins was in high demand. So too were other Australian historians, such as Anthea Hyslop, Paul Sendziuk, Nancy Cushing, and Pamela Maddock. They spoke and wrote about parallels in AIDS and pneumonic influenza, and about vaccination sentiment concerning the militarisation of public health.

For the most part, historians proved unwilling to give either assurances or lessons, though history is always unrepeated, unrepeatable, and instructive. Warwick Anderson, a leading historian of infectious disease ecology and planetary health, was particularly prolific in his efforts to engage critically with the virus. He penned academic articles about disease modelling, public health, and herd immunity, as well as essays in popular magazines, with ever more provocative titles: ‘Think Like a Virus’, ‘Unmasked: Face Work in a Pandemic’, ‘Viral Waste, or Covid Down the Toilet’, ‘Not on the Beach, or Death in Bondi?’, ‘The Virus that Therefore I Am’. Anderson scoured Covid, its collision with human bodies and cultures, and the social fault lines torn open by the impact.

While the virus brought people together in terms of suffering and insecurity, stripping away certain privileges and defences and temporarily exposing the wealthy to some part of what the poorer and more precarious face, it also drove us apart. While the virus itself did not discriminate, it exacerbated existing inequities, and public-health measures underscored other kinds of privilege. Law enforcement was skewed against the powerless; recall the North Melbourne and Flemington public housing tower lockdowns, in July 2020, which were abrupt, heavy-handed, and in breach of residents’ human rights, according to the Victorian Ombudsman. In Sydney, during the same outbreak, the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that public health order fines reflected not patterns of non-compliance but the practicalities of enforcement, with infringement notices typically issued after people were pulled over for other reasons. Fines were issued disproportionately to the young and vulnerable, including those recently charged with other offences. Protections and exceptions were afforded to some kinds of work and workers, while others were thrust into the path of the virus in so-called ‘frontline’ work, not only in healthcare and emergency services but in cleaning, supermarkets, and aged care.

There were subtler divisions, too, in the way society was reconfigured in and out of lockdown. In Australia, some impositions were peculiar to Melbourne, with its severe and frequent lockdowns, strict zoning, and curfews; others were linked with socioeconomic or racial indicators, gender, age, household status, relative burden of care. Some were liberated from long commutes and rigid work patterns; others were consigned to working and living in small dwellings. Some devoted themselves, by choice or necessity, to care; weeks or months were lost to coping, helping and surviving; to spelling lists, maths problems, and technical or moral support for countless hours of remote learning. It is well documented that women shouldered most of the increased burden of housework, foodwork, and keeping the peace. And caring for others sometimes took everything people had to give. The mental health of many was pushed to the brink during the pandemic; others lost access to vital care, or were separated from loved ones, especially those in aged care facilities.

These lockdowns also divided the historical community, accentuating existing inequities and transforming what had been differences into debilities. For us, as for others, there were unexpected pleasures as families and found families drew together, but there were also relational strains, inflexible bureaucracies, and inordinate workloads. But we might find a way to count some part of this experience as gain. During the pandemic, we learned to care in new ways – for children and partners, but also for neighbours, parents, and grandparents living alone, even for the body politic. Some saw anew the need to care for those normally treated with systemic carelessness: prisoners, refugees, the homeless, the elderly, employees. As historians of health and medicine, care is a constant in what we teach and research. But how much has it shaped our practice? How might we translate what we learned about care into our writing and teaching? We have much to learn from feminist studies and the environmental humanities, where care has become an organising principle. How might we better practise care for readers, students and families?

We also find ourselves in a rare moment of historical consciousness, a general sense of participating in history and an awareness of its taking shape around us. Much that was thought fixed turned out to be contingent; defences proved penetrable, freedoms conditional. Frontline health workers, premiers, journalists, public health officials, and delivery drivers all played decisive roles during the pandemic. Historians bear significant responsibility for how these years will be remembered. It is our task to divert the desire for historical precedent and assurance into historical understanding. History is not the dredging up of analogies and parallels, but the work of placing such events in the flow of history, exploring the paths that have led us here. And yet we have seen less engagement with Covid by historians than we might have expected, as Australian Historical Association president, Frank Bongiorno, pointed out in early September. As historians of health and medicine, many of us had read about and imagined this struggle between humanity and microbe, but to be caught up in it was something else entirely. Without the god’s eye view of hindsight – without enough distance for detachment – many have been unwilling to wade in with historical thinking. Perhaps, as we consciously became historical actors, drawn up into a global event generally accepted as ‘historical’, some of us felt our ethical relationships with historical subjects shifting uneasily. Others have simply been trying to survive.

The memory and time work is already underway, and it is right that those of us trained in it should take the lead. The lesson that it is never too early to think historically is a final grim gift of the pandemic – a vital analogy, ironically, with that other consuming global event that has been burning slowly into our consciousness: climate change. The changing climate, like Covid, is already registering in death and disaster at great scale, and it has even deeper and more complex causal pathways. Climate change is still more challenging to reckon with because, while we can see historically that all epidemics come eventually to an end, we cannot, try as we might, see the way to any clear or settled climatic future. This only makes the work of history more urgent and crucial: to understand the origins and pathways of these leviathans and to find our place within them.

This is one of a series of politics columns generously supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

Comments powered by CComment