- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Time to be grass again'

- Article Subtitle: Colorado comes to Tasmania

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

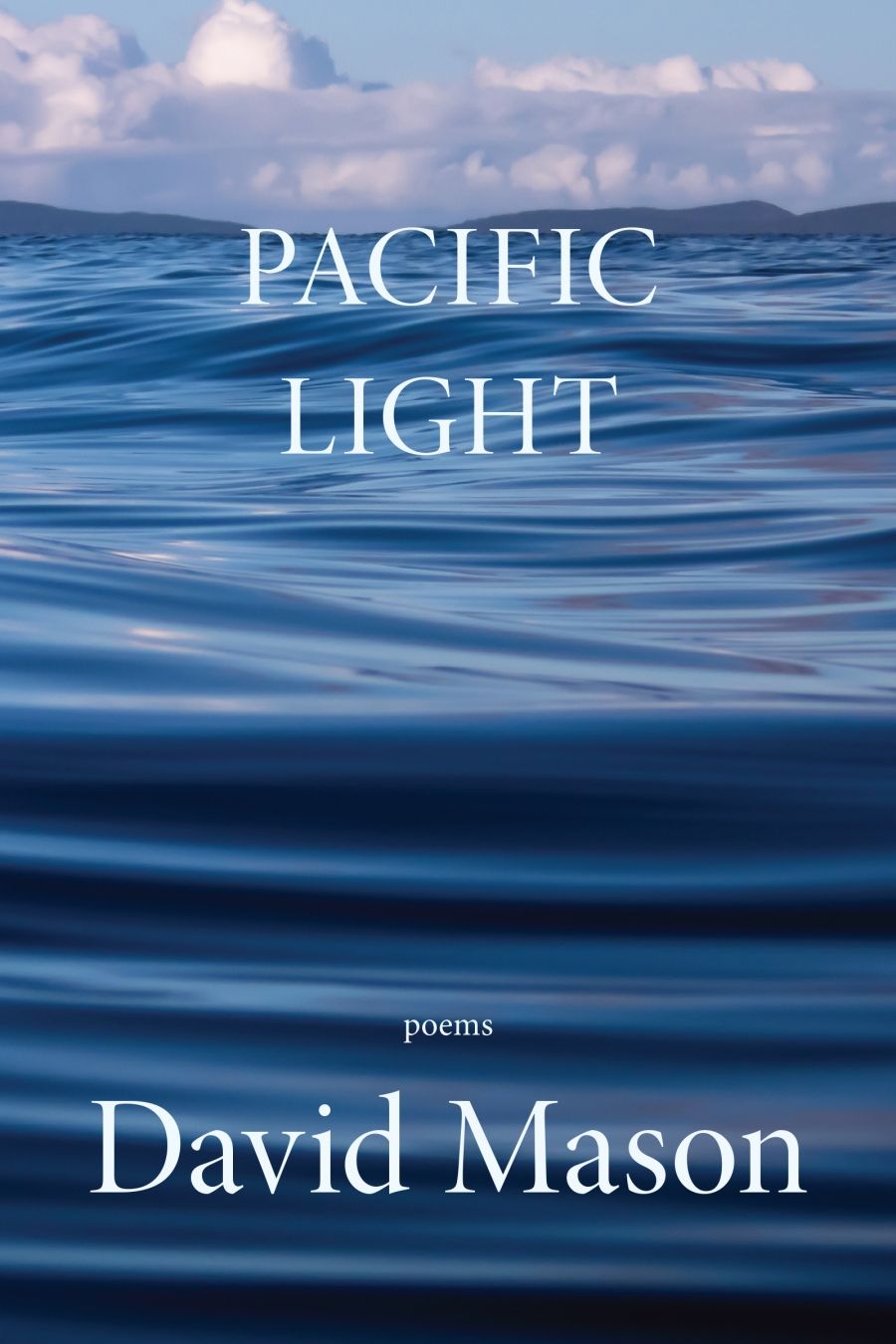

Poet, essayist, and librettist David Mason grew up in Washington State, worked for many years in Colorado (where he became the state’s poet laureate) and a couple of years ago moved to Tasmania. Pacific Light, his new collection, is largely about that transition and his getting to know the landscapes and cultures of his new country.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Geoff Page reviews 'Pacific Light' by David Mason

- Book 1 Title: Pacific Light

- Book 1 Biblio: Red Hen Press, US$17.95 pb, 96 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/pacific-light-david-mason/book/9781636280578.html

Pacific Light is presented in one continuous section, the poems dealing with both Australian and American subjects arranged in no observable order. Mason’s Washington State childhood is a key ingredient, but so too is his accommodation to the Tasmanian landscape (and, provisionally, Tasmanian history). Scattered throughout are more personal poems not anchored in any particular place.

Both the first and last poems here are of this kind. In ‘On the Shelf’, the poet envisages his earlier books as huntsman’s skins, ‘habitations I once thought were home’, before going on to imagine a reader ‘find(ing) some words of mine in an old book. / I meant them. The words. Every one of them, / but left them on the shelf to go on living.’

The book’s final poem, typical of a number in the collection, has a similar emphasis on duration – and is short enough to print in full: ‘To be old and not to feel it is a gift. / To be supplanted and not to care. So be it. / The birds are not supplanted by the air, / the air, what’s left of it, by flood or fire. // The effort of a life, the wasted hour, / the kind word given to a stranger’s child / are understood as kin and disappear. / Time to be grass again. Ongoing. Wild.’

In between are other poems roaming back over the poet’s life and musing on the pleasures (and intermittent sadnesses) of becoming, at an older age, a stranger in a new land. Some of these pleasures are found in ‘Crossing the Line’, which talks of ‘Terra Australis, the Southern Land / that Europeans took so long to find, / and next across the Southern Ocean where // the albatrosses dream between the swells, / unwritten whiteness shrinking toward the pole. / She turned me upside down and brought me here // to walk upright under the Southern Cross’.

On the other hand, Mason is not necessarily in love with all he sees in his new home. ‘An Anniversary’, for instance, begins with: ‘The engines of the salmon farms are droning …’ and goes on to note: ‘At Oyster Cove Mathinna died, not last / but nearly last of an entire universe.’

A comparable severity can sometimes be detected in some poems based on his experiences as a young man working in very physical jobs. In ‘The Solitude of Work’, the poet recalls captured crabs ‘kept alive in the sharp brine of the bay, / till it was time to butcher them. That job / was harder, breaking a ten-pound crab apart / on a chest-high blade. They sensed death coming / and slowly fought the blade with claws like fists, / and when their shells were gutted, empty things / thrown in a grinder, there was still a smell …’ A poem such as this reminds us of the range of Mason’s work, not only in subject matter but also technically. It’s not a simple book celebrating his new home; nor is it a book of nostalgia. Pacific Light encompasses the full reach of a life well lived, by any definition.

While the rhythm in Mason’s verse is rarely ‘free’ in the manner of Whitman or William Carlos Williams, it is flexible – enhanced by its relative formality rather than being defined by it. His use of a strictly rhymed form, such as in ‘Note to Self’ already quoted, is never formulaic. Traditional expectations are undermined by enjambment, variations in syntax, half-rhymes and other devices that work against any complacent facility. The poems here are hard earned, thought through, and are not to be dismissed in any way as ‘old-fashioned’ simply because they employ devices that have worked well for centuries.

Though Mason (born in 1954) may rhetorically refer to himself as ‘old’, it is quite easy to imagine his making a contribution to Australian poetry hardly less substantial than the one he’s made already in his homeland.

Comments powered by CComment