- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Swatting the drones

- Article Subtitle: Philip Salom’s realist fiction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Philip Salom, now in his early seventies, has been a steady presence in Australian literature for more than four decades. Until a few years ago he was mainly known as a poet. He has published fourteen collections and won two awards for lifetime achievement in that field. Having turned to fiction in 2015, he has now published six novels. In Sweeney and the Bicycles, he returns to themes that have woven their way through much of his fiction: identity and selfhood, family and friendship, damage and healing, unlooked-for and unlikely middle-aged love.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews 'Sweeney and the Bicycles' by Philip Salom

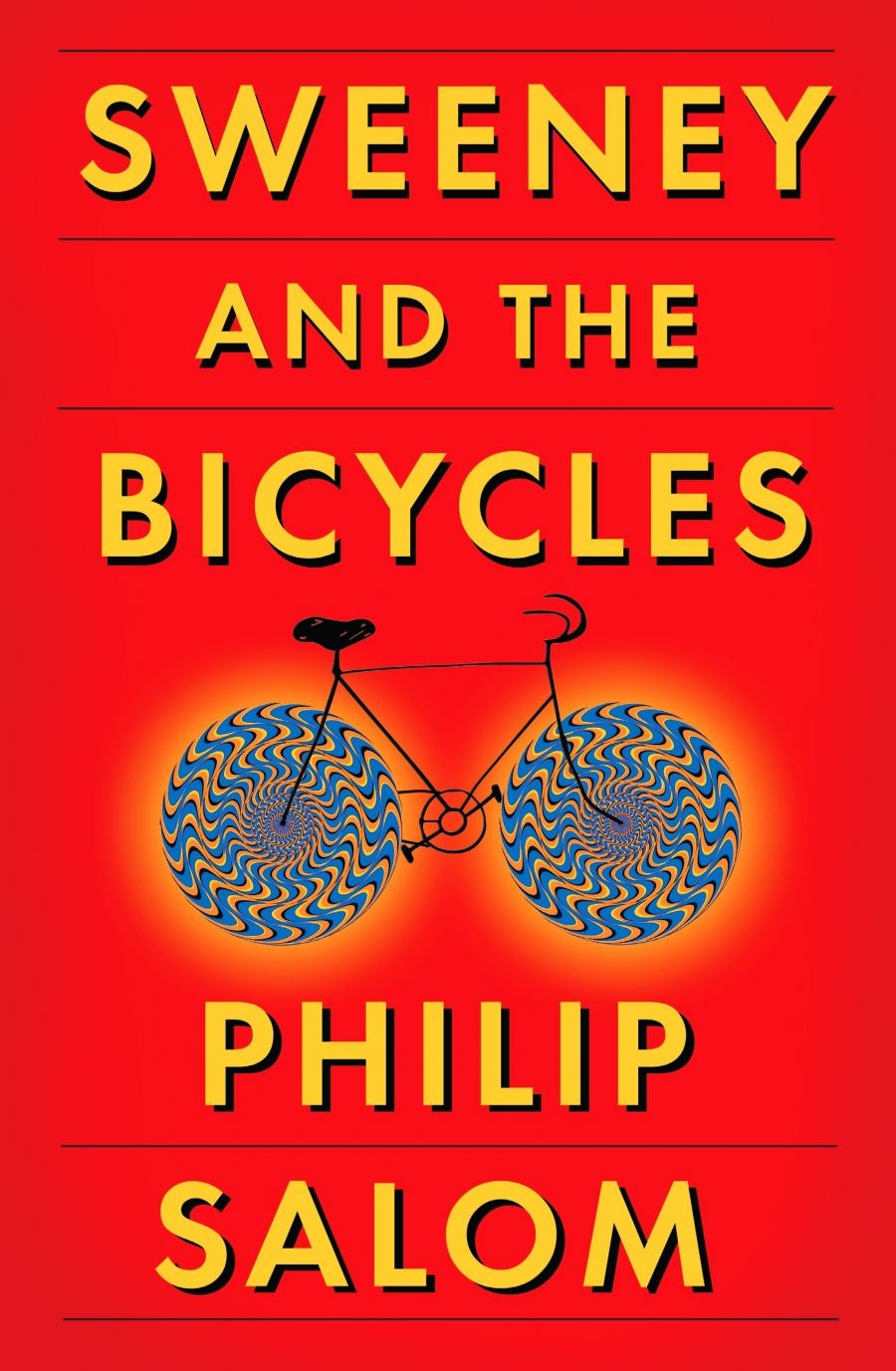

- Book 1 Title: Sweeney and the Bicycles

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $32.99 pb, 408 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/sweeney-and-the-bicycles-philip-salom/book/9781925760996.html

The first character we meet is Sweeney’s new psychiatrist, Asha Sen, who lives with her husband, Bruce Leach, and her stepson, Clifton. Asha also sees a female client called Rose, who has a sister called Heather. All of these people live in variations on and departures from the ideal of the nuclear family. Heather and Rose resemble each other closely and have always lived together, except for a brief blip when Rose was temporarily married. Asha and Bruce are an ill-matched couple in a scratchy marriage. Clifton is an unpromising and sinister stepson. All of the healthiest relationships in this book are between people unrelated to each other, which in itself functions as a gentle critique of families as such. Most of the characters are educated and articulate, and they discuss in detail the moral and philosophical implications of their actions and their work.

Asha and Bruce provide the clearest illustration of this book’s central theme: the nature of identity, and the effects of information technology and artificial intelligence on ideas about the nature of the self. Bruce is the manager of a facial-recognition technology firm, while Asha the psychiatrist explores the psyches, private thoughts, and lives, of her clients:

They are a couple who work in two different worlds of surveillance, the personal identity in her case, facial identity in his, worlds where identity means utterly different things and holds utterly different values. If her vision is empathetic, his is emphatic. And mathematical.

Asha is disturbed by the parallels she sees:

It still troubles me, she says to Leach, the overlap and contrast of our work. How my work is encountering the information formed and stored by neural pathways in the brain … You’re intruding by scanning and collecting people without their permission.

The novel explores other aspects of AI and its implications and potential: data analysis, social media, spying drones. Sweeney is the sworn enemy of this technology and spends time riding around at night, in a disguise that includes some elaborate decoration and painting of his face, blacking out surveillance cameras with a paintbrush. Other more illegal and less ninja-like activities in his past have included the stealing of drugs, which is how he ended up in jail, and of bicycles, which seems an obsession and a sort of bliss. In protracted and detailed conversations about the bicycle thievery, Asha finally helps him to get to the bottom of it.

In this as in Salom’s previous novels, the narrative voice and its world view are mostly warm, generous, and forgiving, but there’s one clear exception: the use of AI for surveillance and other exercises of manipulation and power is clearly, even terrifyingly, explored and condemned, not least through the arguments of the awful Bruce. But Mother Nature, like Sweeney, has been known to fight back: ‘even a determined magpie can bring down a drone and magpies have been known to crowd-bomb the things’.

This satisfying image took me back forty years to the 1981 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Melbourne, the first ever held in Australia, when I was living and working in the inner suburbs of North Melbourne and Parkville, where this book is set. National security was on peak alert, with unprecedented levels of surveillance: all night the helicopters chopped and roared overhead, and in the small hours I would hear the insomniac lions in the nearby Melbourne Zoo roaring back. As I read this novel, I thought about the intervening four decades of technological advancement, and where that advancement is leading us. I wondered what those lions might have thought about hovering surveillance drones, and had comforting visions of strong golden paws, swatting the drones right out of the sky.

Comments powered by CComment