- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Four new poetry collections by Lia Dewey Morgan, Bridget Gilmartin, Daniel Ward, and Shannon May Powell

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Floating in nutrients’

- Article Subtitle: Poetry as an engine of community

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The poetry section is growing at the bookshop where I work. Younger readers huddle together to discuss poems. A science student buys five poetry books to read over semester break. When a retired teacher from out of town comes looking for a Judith Wright book, we get talking, I make suggestions, and he ends up dropping almost $300 on poetry titles. Customers ask for First Nations, Middle Eastern, and queer poets, and they want the canon too, they want to try anything staff find exciting. Readers are seeking ways into poetry. Is it having a(nother) renaissance? The results of this year’s Stella Prize corroborate what I’m seeing on the shop floor.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Four new poetry collections by Lia Dewey Morgan, Bridget Gilmartin, Daniel Ward, and Shannon May Powell

The emphasis on aesthetics is traceable to the characteristics of the milieu; a strong presence of artists run through no more poetry’s contributor list. My feeling is that, increasingly, young, talented creators, many of them visual artists, are taking up poetry right now. A democratic form, it doesn’t require the materials needed for art or music, and can offer an immediacy prose can lack, both in its production and its consumption – I’m referring to the demands of narrative, logic, stretches of time, attention, and so on. Poetry is also a social machine, an engine of community more like music than prose, more naturally performed before a public. As Australia’s housing and cost-of-living crises hits young creators hard, we are reminded at core that we just want to be able to make things and share them with our friends. So we write poems when we can, where we can. Getting together to hear them read is just as important as reading them alone.

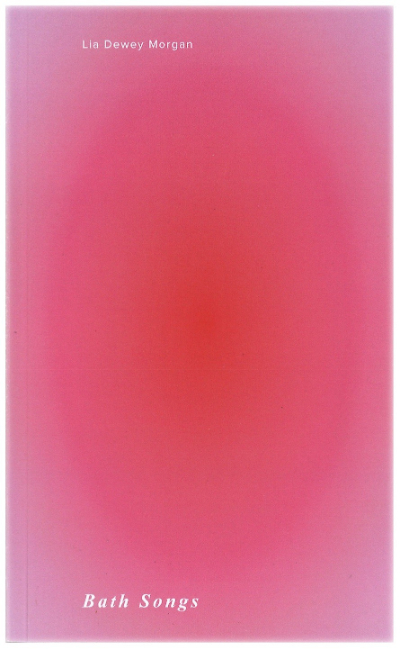

Bath Songs by Lia Dewey Morgan

Bath Songs by Lia Dewey Morgan

no more poetry, $29.75 pb, 127 pp

Bath Songs charts Lia Dewey Morgan’s transition into femininity as they undergo hormone replacement therapy, become hermetic, encounter and recount lovers, and endure lockdowns. These are poems of a self striving, longing, and toying with language, lovers, and their own body. There’s a lengthy introduction where the poet lays out the biographical context for the tonal, formal, and conceptual bases of its three parts. Likely a holdover from their art practice, and while illuminating, it serves to undercut the poems, which should need no justification, no hedging. Yet we are compelled to come along with Morgan as she comes to revel in language. ‘Good god I’m empty,’ Morgan repeats in anguish during the first section. In part two, she embraces Japanese tanka poetry, ‘trembling in and out of form’. In part three, out of the early stages of transition and now ‘shaking off’ prior form the poet unfurls an incantatory poetics embracing repetition: ‘Remembering time // stretching and breaking? // Barking! // The sound slowing down // ripping tone into pulse.’ ‘Remember marching // in your words // setting worlds // in the chassis // of a letterpress?’ The arc of the book renders their transition vivid in a playful, resonant poetics of emergence.

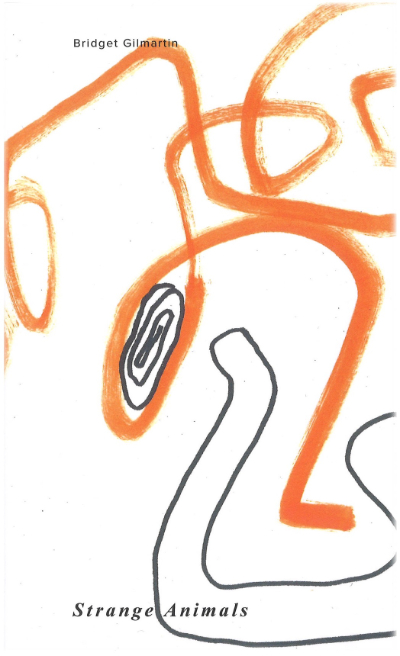

Strange Animals by Bridget Gilmartin

Strange Animals by Bridget Gilmartin

no more poetry, $25 pb, 69 pp

Bridget Gilmartin’s Strange Animals asks us to consider the implications of judgement. While tangled in enigmas of identity, the self, and the texture of relationships, these poems show a deep desire for understanding, for compassion. Usually with a friend or a lover, Gilmartin is at the beach, the cafe, the bed, the pool, the supermarket, the restaurant, the park, the couch, the motor inn et al. It’s telling that, despite feeling judged, Gilmartin rarely judges others. There’s a rugged ease to these poems, they’re built simply and they work. They’re intimate, they accumulate, nudging us towards pathos. It’s my favourite of the bunch.

lying on my back

at Northcote pool

I imagine the chlorine

is embryonic fluid

my limbs

floating in nutrients

from somewhere

in my periphery

a kid says

mum,

is that a boy

or a girl?

honey,

it’s a girl

I open my eye

squint the sun

like a

hospital light.

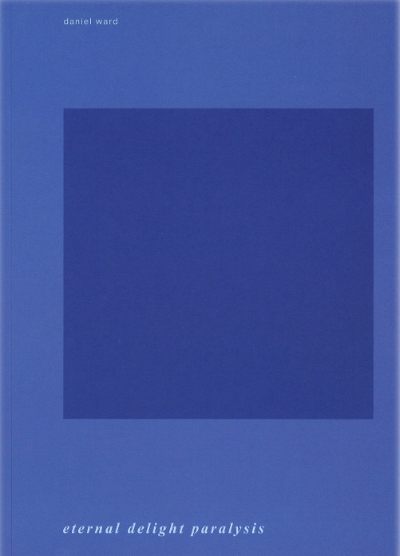

eternal delight paralysis by Daniel Ward

eternal delight paralysis by Daniel Ward

no more poetry, $35 pb, 148

Daniel Ward is the editor of no more poetry, and eternal delight paralysis (no more poetry, $35 pb, 148 pp) is their second book of poems. Oscillating between apathy, the pursuit of pleasure and broader philosophical concerns, Ward writes with a cleverness and self-assuredness that hums when in the second person, often addressing the lover, or the first-person plural, invoking a collectivity that elevates the work above the hot take:

when we are open we welcome more and more but we are suspended and here we are more malleable and to be malleable maybe is not to be cool which is to be stoic or sure or stubborn, but in this room it pays to be open and this feels disorientating

Can we rest tonight in the amnesia of pleasure by Shannon May Powell

Can we rest tonight in the amnesia of pleasure by Shannon May Powell

no more poetry, $45 pb, 98 pp

Shannon May Powell’s Can we rest tonight in the amnesia of pleasure is a book of poems exploring sex, the body, and gender. It is bound by two Chicago screws and features thirteen fold-out colour photographs taken by the poet. The book is a sumptuous object that struggles to generate in its poems the eroticism promised in the printed images and title. The language here is too often stilted and glossy, lacking in the gristle and frisson conjured by the collision of real bodies.

Stuck in the shared trance of love

we created whole imaginary worlds

Each lingering gesture

a sacred prop

in the theatre of our home

Performing my gender

like a magician or mime

Me with my painted smile and heavy eyes

drawing back the curtains

of our invisible arrangement

to take a final bow.

When Can we rest tonight in the amnesia of pleasure was launched in May, I was there at the Collingwood Arts Precinct amid a sizeable crowd. It was cosy, almost decadent, and we were all a little cagey, waiting for the occasion to crack open, for someone or something to set fire to the night, to delight us. The moment teetered but was elusive. Ward’s sentiment from above, ‘in this room it pays to be open and this feels disorientating’, feels apt. Poetry is dizzying, poetry is the articulation of difference, and that’s risky business. People are coming to poetry, and the minds, bodies, organs, rooms, and poems themselves should open up to this, should relish this, should get dizzy with the implications. Yet openness demands courage, vulnerability, faith in one another – a certain hospitality. I think no more poetry represents a wave of coming to poetry, and this is exciting. I’m eager to see what’s next from these poets and this press, and how they’ll continue to articulate their difference.

Comments powered by CComment