- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nuclear Australia

- Article Subtitle: Uranium diplomacy in a changing world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 15 September 2021, Scott Morrison announced his government’s commitment to a defence pact and nuclear submarine deal with the United Kingdom and United States. Abbreviated to AUKUS, this collaboration sent shockwaves through ranks of diplomats, security analysts, anti-nuclear advocates, and members of the Australian public. In signing the AUKUS pact, Morrison signalled Australia’s termination of a $90 billion submarine deal with the French government and reignited concern over Australia’s role in fuelling nuclear proliferation and potential conflict. Drawing upon ‘insider’ knowledge as a former diplomat, Richard Broinowski has contributed to the discussion by placing AUKUS in its historical context in an updated edition of his book Fact or Fission? The truth about Australia’s nuclear ambitions, originally published in 2003.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

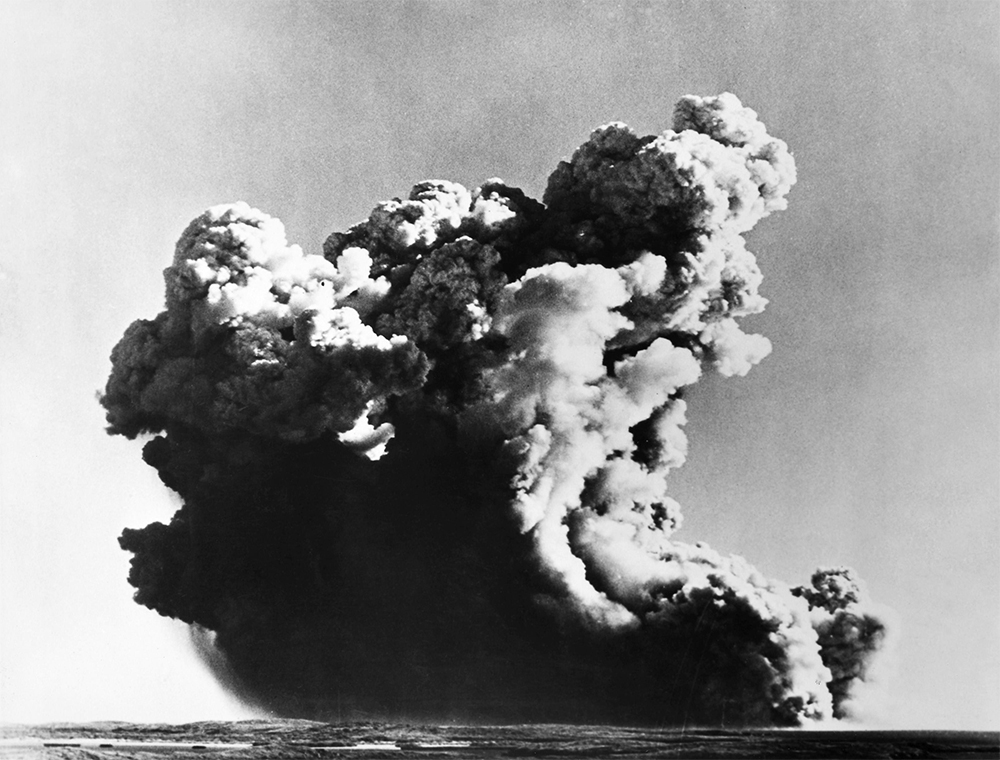

- Article Hero Image Caption: Great Britain tests its first atomic weapon at the Montebello Islands off the coast of north-western Australia, 1952 (photograph via Granger/Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Great Britain tests its first atomic weapon at the Montebello Islands off the coast of north-western Australia, 1952 (photograph via Granger/Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jessica Urwin reviews 'Fact or Fission: The truth about Australia’s nuclear ambitions' by Richard Broinowski

- Book 1 Title: Fact or Fission

- Book 1 Subtitle: The truth about Australia’s nuclear ambitions

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kjr4ML

Like its first edition, the updated iteration of Fact or Fission? takes its reader on a journey through Australia’s nuclear policy history from the 1940s to today, beginning with the eminent careers of Professor Mark Oliphant and H.V. (‘Doc’) Evatt and ending with AUKUS. Taking a policy focus, Broinowski demonstrates the role of diplomats and experts in shaping Australia’s early nuclear ambitions by exploring Australia’s postwar interest in contributing to a Commonwealth nuclear posture. This focus early in the book foreshadows the role Australia would come to play as a middle power in global nuclear diplomacy through the later twentieth century. In developing this narrative, Broinowski discusses at length Australian diplomats’ debates over, and involvement in formulating, international nuclear safeguards, guided by Australia’s alliance with the United States.

Entwined with Broinowski’s discussion of nuclear safeguards are the history and politics of uranium. Describing Australia as ‘the Saudi Arabia of uranium’, Broinowski reveals how various prime ministers – from Robert Menzies through Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, and John Howard – have approached the issue of uranium mining while remaining amenable to their ‘great and powerful friends’. In the 1950s and 1960s, for example, Australia failed to make the most of potential uranium profits due to concerns that exporting the mineral to France and Japan would undermine Australia’s relationship with the United States. Despite this, by the late 1970s uranium mining and exportation were a major part of the government’s agenda.

Australia’s exportation of uranium has been historically justified, at least by Fraser, as contributing to the global non-proliferation agenda by controlling who receives Australian uranium. This is an illusion Broinowski demystifies. He demonstrates that the tracing of Australian nuclear material has always been impossible. Ultimately, the mining and exportation of Australian uranium has not been bound by the global non-proliferation regime, but driven by a desire to appease the Australian mining lobby and to safeguard Australia’s defence alliance with the United States. Such priorities, Broinowski posits, have degraded Australia’s non-proliferation credentials over time. AUKUS may be the final blow.

In this context, among others, Australia’s commitment to its defence alliance with its ‘great and powerful friend’, the United States, is a topic of contention throughout Fact or Fission?. We can certainly count Broinowski among its critics. He dwells for some time on Howard’s approach to the nuclear between 1996 and 2003. Howard’s policies, Broinowski argues, reflected his blind subservience to President George W. Bush. Due to post-9/11 instability, Australia’s deference to the United States on all matters relating to Australia’s defence appeared especially dangerous to Broinowski at the time Fact or Fission? was originally published. Morrison’s comparable obsequiousness forms part of the book’s update.

To bring the story up to date, Broinowski has added a final chapter on Morrison’s commitment to AUKUS. In doing so, Broinowski has had to grapple with the eighteen-year gap between the first edition’s publication and the current period of considerable change in Australian – indeed global – nuclear diplomacy. Arguably, it is Broinowski’s conclusion, not his discussion of AUKUS, that demonstrates most acutely the developments in nuclear diplomacy since 2003.

Notably, fears of nuclear terrorism have given way to fears over China’s rise. In the introduction to Fact or Fission? – unchanged since 2003 – Broinowski argues that the 9/11 terrorist attacks demonstrate the potentially devastating consequences of nuclear terrorism in the early 2000s. In 2022, the mention of Al Qaeda seems out of place. So too do overt fears of nuclear terrorism; the issue fails to prompt headlines as it used to. As Broinowski explores in the final pages, concerns over rising tensions between China and the United States have led contemporary experts to instead speculate about the renewed threat of nuclear war.

As this suggests, the international normative landscape has changed. In 2017, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was adopted. During negotiations, Aboriginal nuclear survivors provided moving testimonies to the United Nation’s General Assembly. The Australian-based International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its campaign in support of the treaty. Commentators argue that the TPNW marks a significant normative shift away from nuclear weapons by many of the world’s non-nuclear-weapons states. But, Broinowski points out, Australia’s inability to sign or ratify that same treaty reflects its continued subservience to the United States.

In offering his readers an updated ending to a largely unchanged book, Broinowski demonstrates the stark differences between contemporary nuclear diplomacy and that which existed in 2003. At the very least, nuclear terrorism is no longer at the top of Australia’s list of nuclear concerns. Nor can any of the nuclear powers now honestly maintain that their nuclear weapons aren’t widely condemned. Only time will tell whether the recent election of the Albanese government will assist in restoring Australia’s shattered non-proliferation credentials.

Comments powered by CComment