- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tangible results

- Article Subtitle: Reflections of a literary jurist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Nicholas Hasluck is that relatively rare combination of practising lawyer and accomplished writer. A former judge of the Supreme Court of Western Australia, he has also produced more than a dozen novels and as many works of non-fiction. This duality of roles is not unknown. Two contemporary examples that come to mind are Jonathan Sumption, who was on the UK Supreme Court and is a medieval historian, and Scott Turow, a Chicago attorney whose works include the trial novel Presumed Innocent (1988).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

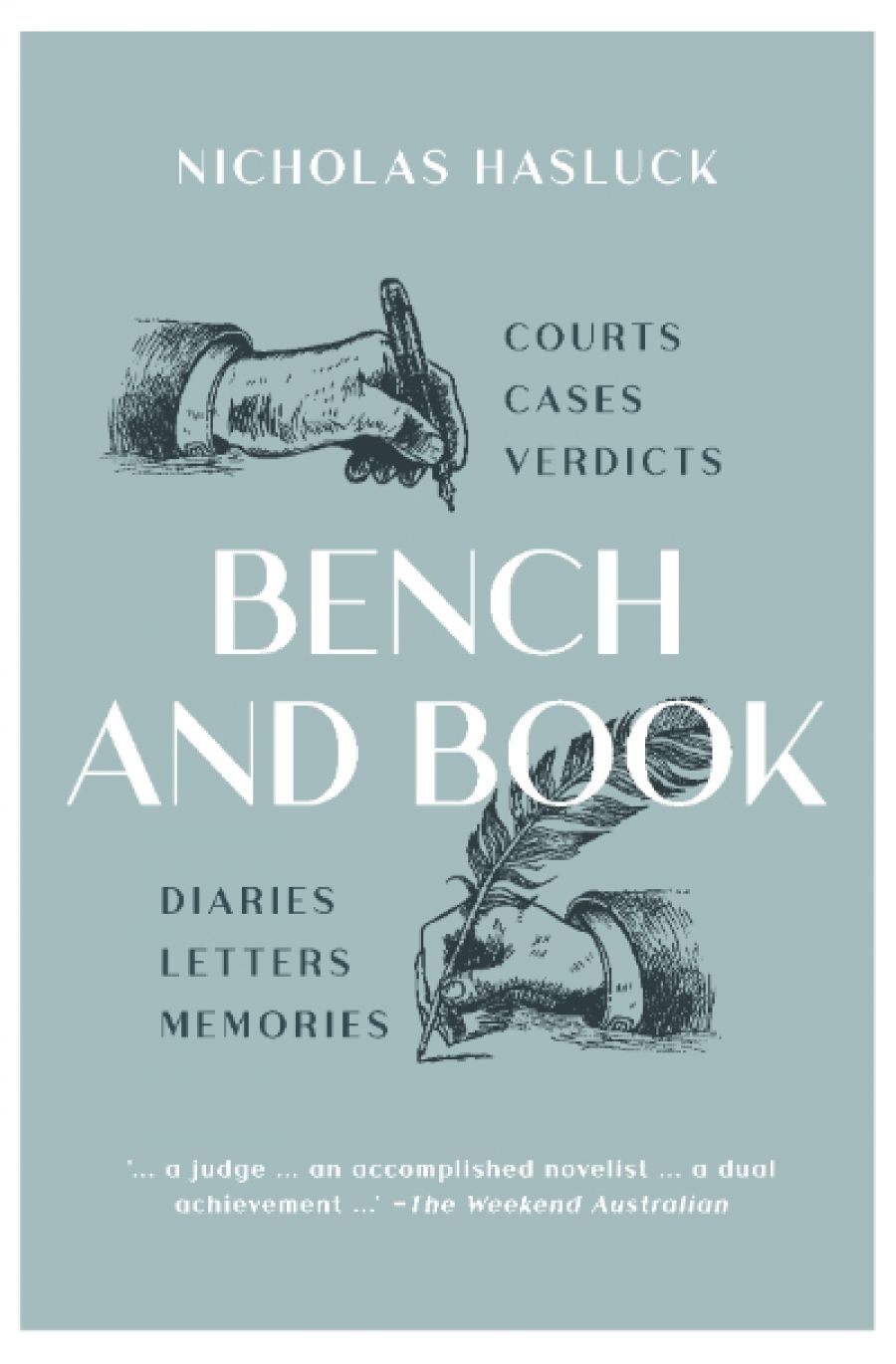

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Sexton reviews 'Bench and Book' by Nicholas Hasluck

- Book 1 Title: Bench and Book

- Book 1 Biblio: Arcadia, $44 pb, 348 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2rNbk0

He speculates on one of the reasons for this view:

The language used by lawyers aims for precision, in court or in drafting documents or while advising … This eventually entrenches a belief in most legal minds that one needn’t bother about literature because it simply doesn’t count. It speaks in a way that is imprecise and often misleading. It doesn’t lead to tangible results.

The book takes the form of diary entries for the years 2000 and 2001 when Hasluck was, for most of this time, a member of the Western Australian court and also chair of the Literature Board of the Australia Council. Diary entries are a difficult species of literature. It is easy to say that Harold Nicolson’s diaries from the 1930s and 1940s were a great success, but Nicolson was not only a good writer: he was moving among the nation’s leaders and against a background of momentous events, including World War II.

The first entry in Bench and Book is far from promising: ‘A busy day at Bar chambers, checking mail at my desk and a new brief. Later, over a beer in the common room, badinage with fellow barristers about a rumour doing the rounds that I might soon be filling a vacancy on the Supreme Court.’ This rather lacks the sardonic touch of Rumpole, but things do improve after that. Subsequent entries give a good picture of judicial life, including the difficulties of presiding over criminal trials and the sometimes harrowing decisions as to whether to send convicted persons to prison or not, although many of Hasluck’s colleagues on the bench do not seem to be much affected by these life-changing choices.

Prior to life on the bench, Hasluck was a barrister; he makes an astute observation of that side of the profession: ‘To enjoy life as a barrister one has to be supremely self-confident, be unaffected by doubt, and have a thick hide. The reality is that my skin hasn’t been thick enough and my imagination has been too fertile, too conscious of the pitfalls.’ There are, of course, exceptions to this generalisation, but not many in my own experience at the Bar.

Hasluck includes accounts of some of the civil and criminal cases over which he presided as a judge, although it must be acknowledged that civil cases, such as building disputes and insurance claims, while of great importance to the parties, are seldom of general interest.

Hasluck spends quite a lot of time travelling to other parts of the country for meetings of the Literary Board and the Australia Council. The deliberations of the Board over which authors are to get federal financial grants do not sound particularly edifying, as Board members engage in horse-trading over their choices. The meetings of the Australia Council sound even worse, full of bureaucratic language and rendered more unintelligible by a hired facilitator.

In these roles, Hasluck was a constant attendee at interstate literary festivals. At one point, he complains about the lack of differing viewpoints at writers’ festivals, despite the ostensible desire for diversity of opinion. This was a complaint made in 2000; if he were to attend a literary festival now, he might deem the situation much worse than it was twenty years ago.

Hasluck is very protective of the reputation of his father, Paul Hasluck, a long-time federal minister in the Menzies era and later governor-general. There is, however, no reference to the fact that, as foreign minister between 1964 and 1969, his father was one of the architects of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. There is much debate about his reputation in that role.

Given that so few judges write about what they do, Hasluck’s book is a valuable account of judicial life, particularly for non-lawyers, and not least because it underlines the vagaries and uncertainties of litigation. Most litigants are convinced of the merits of their case but, as this book indicates, once a matter goes to court there are inevitably going to be arguments on both sides and it is often difficult to predict how it will ultimately be resolved. This is why, even in the High Court, there are occasions where the seven judges divide four to three on the result in a case. It is no consolation – quite the contrary perhaps – to the losing litigant that he or she persuaded three of the nation’s leading legal minds that the arguments for that side were correct.

Comments powered by CComment