- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Defined by death

- Article Subtitle: Another take on the Cowra breakout

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

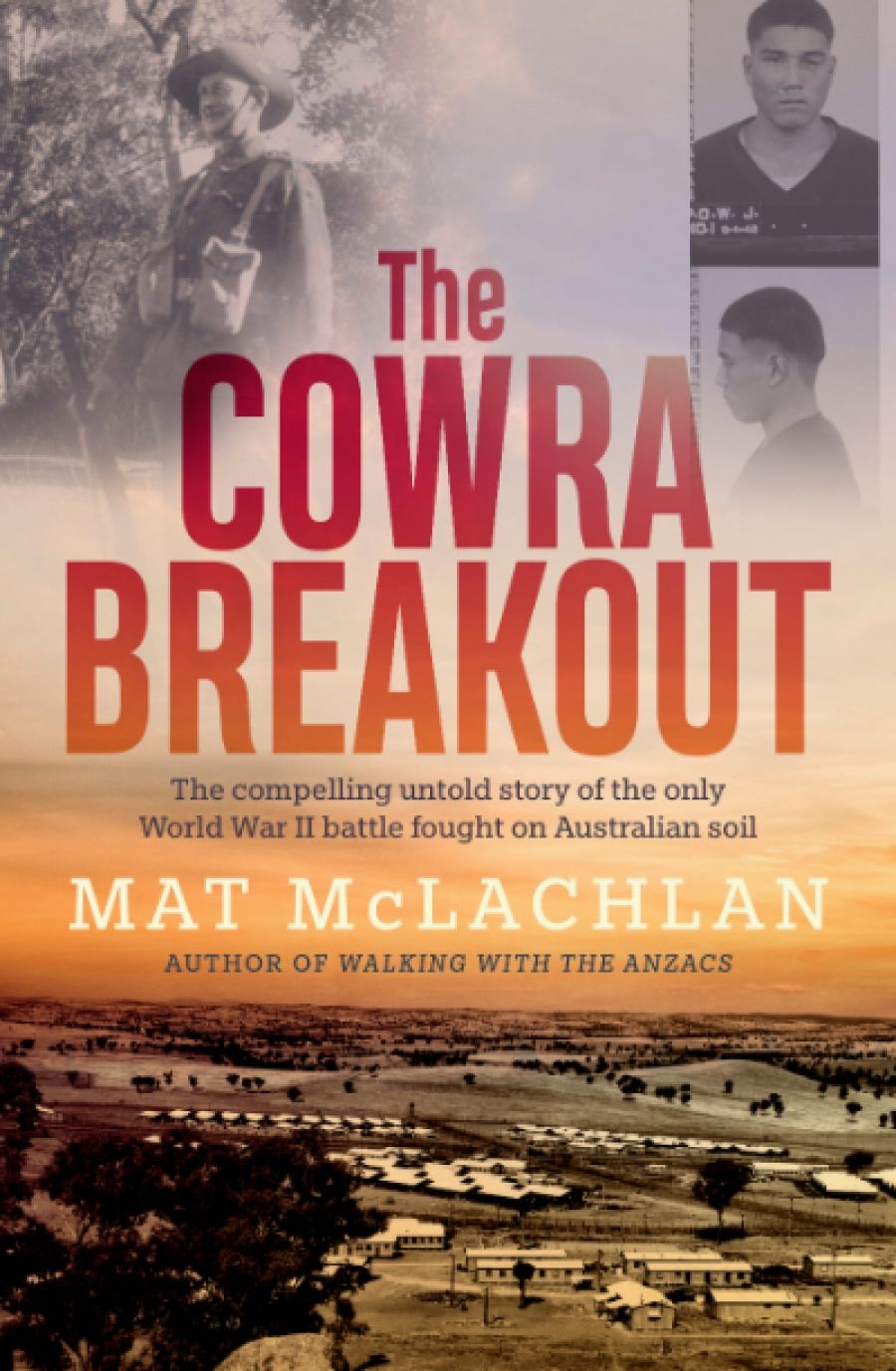

Why do publishers do this? The cover of this book screams that the Cowra breakout is an ‘untold’ story, and ‘the missing piece of Australia’s World War II history’. Neither claim is remotely true, as the author himself acknowledges. Once we get past the sensationalist cover and into the text, Mat McLachlan notes that the story of the Cowra breakout has been told several times before, and well: he even salutes Harry Gordon’s Die Like the Carp!, first published in 1978, as the ‘definitive’ account. So this is hardly the missing piece of an Australian military history jigsaw. Another stretch is the suggestion in the shoutline that the breakout was a conventional military ‘battle’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Burial of Australian soldiers killed during breakout of Japanese prisoners at B Camp. Australian War Memorial, 044119 (From the book under review)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Burial of Australian soldiers killed during breakout of Japanese prisoners at B Camp. Australian War Memorial, 044119 (From the book under review)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Seumas Spark reviews 'The Cowra Breakout' by Mat McLachlan

- Book 1 Title: The Cowra Breakout

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 322 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/BXMmEB

These cover claims tell us as much about the marketing plan for this book as its contents. I suspect that McLachlan and his publisher had an uncritical audience in mind. The first pages follow the Peter FitzSimons model, with events and interactions extrapolated from seemingly scant evidence. I qualify the claim because there are few references, meaning that readers cannot check the evidence for themselves. FitzSimons has described himself as a ‘storian’ rather than a historian, a position which allows for the idea that telling a good tale counts for more than the pesky facts, or lack of them. It’s not an approach that demands imitation.

Another feature of this work is the resort to clichéd language and stale concepts of wartime identity. The stereotype of Italian soldiers as inept and emotional has a long history in Australian military scholarship, and it appears here. Italian prisoners at Cowra were ‘slightly comical’, ‘passionate and dramatic’, and ‘naturally charismatic’. Japanese soldiers, meanwhile, were devoid of ‘individuality’ and ‘independent thought’, though evidently the author knows otherwise for he offers examples to the contrary. The pity of all this is that McLachlan can write. Despite the clichés and other detours to the easy and comfortable, I enjoyed this book. McLachlan is a natural, engaging writer, his voice strongest and most appealing when not imitating the approach of others.

An archipelago of internment camps emerged across rural Australia in World War II. Several of these camps were at Cowra, about 230 kilometres west of Sydney. Cowra was home to prisoners of war from different backgrounds, including many Italians and, most famously, Japanese prisoners. On 5 August 1944, about 1,000 Japanese POWs attempted to break out of their camp, with around 380 succeeding in escaping into the countryside beyond; most simply waited to be recaptured. These statistics give Cowra an unlikely place in history as the site of one of the world’s largest prison escapes.

In a series of detailed chapters, arranged chronologically, McLachlan explains the motivations and catalyst for the breakout, and its tragic aftermath. For some Japanese POWs, crippled by the shame of being taken prisoner, their motivation was simple. They wanted to die, and saw the breakout as a means to achieve this. Wartime escape stories lend themselves to false notes, the pain and subjugation of prisoners made trivial in the pursuit of a romantic, stirring story. McLachlan does well to avoid this trap, making clear that the Cowra breakout was defined by death. Around 230 Japanese died brutal and gruesome deaths in the mass escape. Some killed themselves.

Five Australian soldiers also died. Histories of the breakout usually have that number as four, but McLachlan makes

a convincing case for adding the name of Sergeant Tom Hancock to the list of Australian deaths. Hancock’s name is not usually linked to the breakout because his death occurred in Blayney, a town about seventy kilometres from Cowra. But he too was a victim of the breakout for he died while on duty as part of the Australian response to the mass escape. He was killed when a gun discharged accidentally.

There are signs of haste in the research and writing of this book. Early on McLachlan writes that ‘Australia’s internment program is a fascinating and overlooked chapter of the Second World War’. Peter Monteath, Christina Twomey, and Yuriko Nagata, to name three scholars, have written at length about World War II internment in Australia, with Nagata’s work of particular relevance to this book. Over the past thirty years, she has produced original and important work on Japanese prisoners in Australia. A stronger command of these sources may have led McLachlan to temper some conclusions: indeed, there is much ‘astonishment’ and indignation in his findings. Are his findings new, or is he just late on the scene? It isn’t always clear. There is a scattering of typos, and instances of repetition and contradiction, which a stern editor would have cut.

After the war, the people of Cowra were quick to care for Japanese graves in their midst, their actions made all the more noble given the bitter anti-Japanese sentiment of the period. ‘Weary’ Dunlop aside, not many Australians were brave enough to choose forgiveness over animosity when it came to the wartime enemy. From this and other humane gestures there arose a remarkable connection between the people of Cowra and some Japanese connected to the breakout, their link strengthened by a shared commitment to peace and goodwill. The most powerful evidence of this commitment is the Japanese war cemetery at Cowra, opened in November 1964. It is the only Japanese military cemetery in the world outside Japan.

McLachlan writes about this postwar history with feeling and verve. This is perhaps the most interesting and important aspect of the Cowra breakout, and the least known. If there is a story in this book that deserves a wider telling, Mat McLachlan finds it in the last few pages.

Comments powered by CComment