- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Contested seascapes

- Article Subtitle: The leaky ideology of marine freedom

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In early 2020, as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic took hold, a special kind of viral hazard appeared upon the surface of the sea. Offshore from Sydney, Yokohama, San Francisco, and elsewhere loitered cruise liners turned floating hot spots. As they awaited permission to dock and disembark their passengers, the boats became an inadvertent exhibition of cruising-industry foibles. Behind sluggish and patchy Covid action plans, we learned, lurked other forms of misbehaviour, from grotesquely unscrupulous labour practices to systematic tax avoidance. The high seas, it seemed, really were wild.

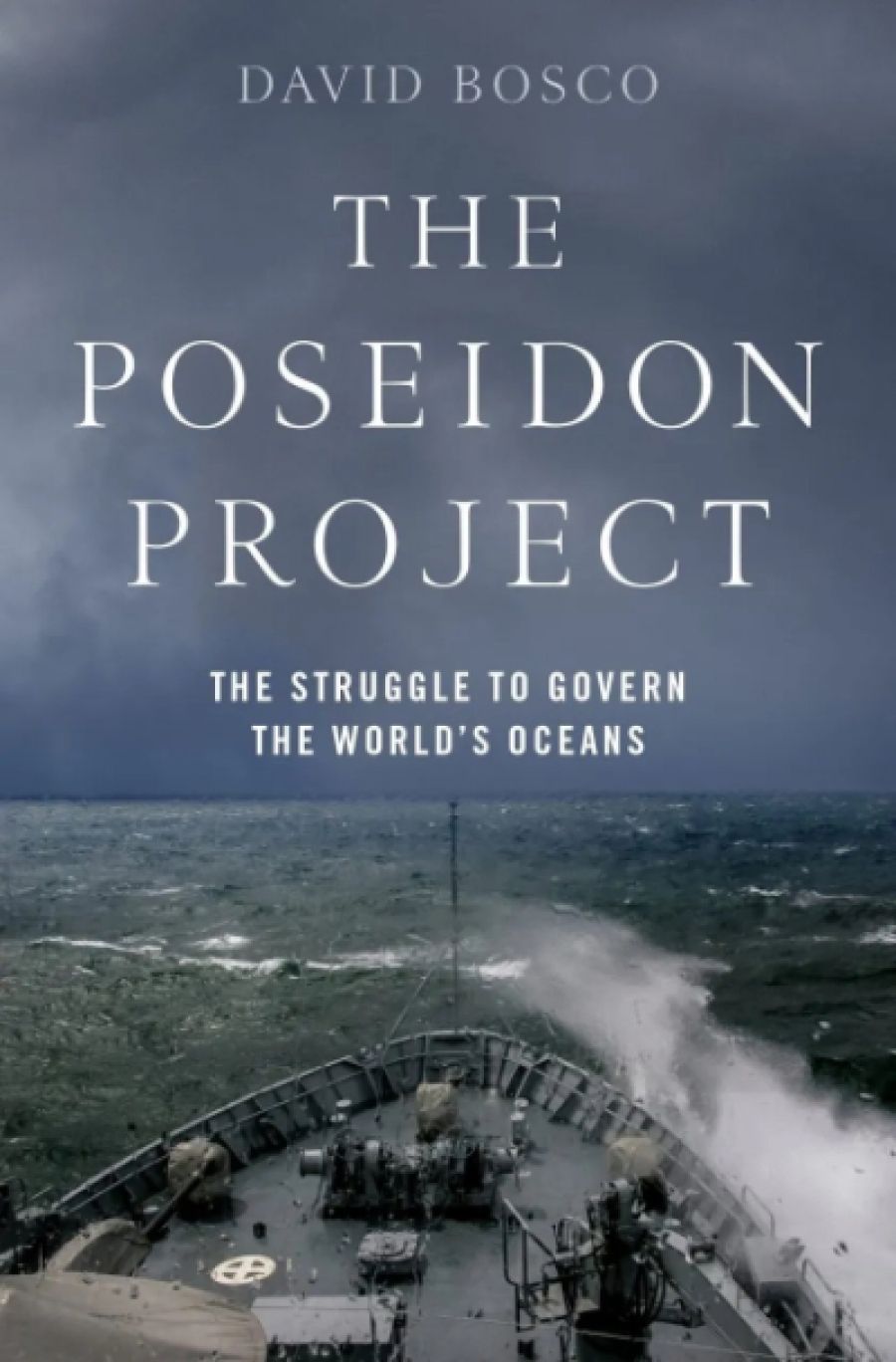

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: The aircraft carrier USS Constellation in the South China Sea during the Vietnam War (GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): The aircraft carrier USS Constellation in the South China Sea during the Vietnam War (GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Killian Quigley reviews 'The Poseidon Project: The struggle to govern the world’s oceans' by David Bosco

- Book 1 Title: The Poseidon Project

- Book 1 Subtitle: The struggle to govern the world’s oceans

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £22.99 hb, 315 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/gbEMPg

A new book from the legal scholar David Bosco helps us understand what was – and still is – going on. The Poseidon Project: The struggle to govern the world’s oceans is a magisterial history of a well-known but poorly understood ideology of marine governance known as ‘freedom of the seas’. This is the doctrine that has come to hold, among other things, that a vessel travelling outside territorial waters is subject to no authority but that of the nation where it is registered. It is also, and uncoincidentally, the logic that has made popular the ‘flag of convenience’ arrangement, whereby a seagoing boat – a cruise ship, say – flies whatever ensign happens to incur the least onerous regulatory compliance. Neither natural nor inevitable, the freedom of the seas emerged from and exists under conditions of contingency and dispute. Whether it is likely to survive the present, as sovereign governments and international agencies claim more and more control over oceanic space, is The Poseidon Project’s ultimate concern.

If the freedom of the seas has a history, then what preceded it? In Bosco’s nimble telling, ancient and medieval protocols of marine governance were diverse in their origins but united in their preoccupations. From the Indian Manusmriti to the Rhodian Sea Law to the Islamic Treatise on the Leasing of Ships and the Claims between Parties, premodern frameworks for managing maritime affairs were less concerned with refereeing territorial rights to the sea than with the finer points of regulating seagoing travel and trade. Priorities shifted – in and from Europe, above all – following the transoceanic, state-sponsored navigations of Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Ferdinand Magellan in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Novel questions arose regarding how a sovereign power might assert and exercise command over part or all of the world ocean. Novel answers appeared, too: as burgeoning imperial powers like Spain and Portugal struck treaties to divvy up the seas, maritime space became internationally politicised in unprecedented ways.

As other aspirants to marine dominion arrived on the scene, the issue of who controls the oceans became increasingly controversial. Around the turn of the seventeenth century, a series of unsavoury maritime incidents prompted a juridical debate that Bosco calls ‘the battle of the books’. The skirmish was scholarly, but it was not disinterested: the lawyer Hugo Grotius, whom history has crowned the winner, was arguing on behalf of the Dutch United East India Company, a chartered entity then embroiled in violent disagreements with the Portuguese respecting Indian Ocean trade. Grotius’s Mare Liberum, or Free Sea (1609), contended that it is impossible to possess the ocean in the same way as land, because to own something one must be able to occupy it. His position’s great strength, Bosco observes, was that it was based not in divine authority but in natural law. As the seas were becoming free, they were also becoming modern.

Whatever its philosophical merits, what made the freedom of the seas endure was its convenience for Earth’s emerging maritime hegemon. As its navy grew and its overseas entanglements multiplied, Britain became an outspoken proponent of open oceans and the benefits they furnished. Here and elsewhere, Bosco reminds us that commitments to marine mobility have always manifested ‘positively’ as well as ‘negatively’. That is, they have always taken shape as much through the active policing of pirates and other nuisances – perceived or actual – as through the forswearing of claims to saltwater territory. The privilege of maintaining this equilibrium fell to the power capable of enforcing it. From the latter part of the eighteenth century to the eve of World War I, that power was overwhelmingly British. Unsurprisingly, therefore, if the ‘Grotian ideal’ was by the early 1900s ‘in full bloom’, its flowering was neither globally representative nor universally beloved.

Nor could it survive the Great War unscathed. Two interrelated phenomena conspired against it: submarine warfare upon merchant vessels and the ensuing, extraordinary enclosure of maritime space by nations desperate to protect shipping. The securitisation of the sea only intensified before and during World War II, and its legacy persisted into peacetime – if not in the form of military blockades, then in ‘protective zones’ designed to safeguard national fisheries. A newly ‘acquisitive’ era was being born, thanks particularly to the rising fortunes and brazen unilateralism of the United States. Claims to sovereign control over continental shelves and water columns proliferated, and the Grotian ideal continued leaking.

The postwar pursuit of marine territory helped set the stage for momentous efforts toward oceanic internationalism. Especially pivotal were the labours of Arvid Pardo, Maltese ambassador to the United Nations and theorist of a possible successor to Grotian freedom. At a series of UN conferences on marine law, Pardo helped lead the case for designating the sea-bottom and its mineral treasures the ‘common heritage of mankind’. This was a potentially transformative swerve away from the winner-takes-all status quo, and its prospects for acceptance by the historical winners were correspondingly dubious. Nevertheless – and despite the concerted interference of the United States – when the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) finally came into effect in 1994, it included among its innovations the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a body exercising jurisdiction over some one hundred and fifty million square miles of ocean floor – over ‘more territory’, in Bosco’s words, ‘than almost any head of state’.

Still, if UNCLOS has a defining legacy, it is probably the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), an instrument for consolidating national control over oceanic resources as far as two hundred nautical miles beyond a country’s shoreline. The freedom of the seas, therefore, was getting squeezed from two sides: from the sovereign expansions effected by EEZs, and from multilateral mechanisms like the ISA. For Bosco, it is the volatile interplay of all these energies that has constituted the state of marine governance in the twenty-first century. Whether this unsteady ‘maritime compromise’ survives ongoing struggles for dominance in the South and East China Seas, among other places, is unknown.

Whatever eventuates, writes Bosco, the ‘idea of the high seas as an unowned and minimally regulated space’ continues – and will continue – to weaken. Issuing from a study as marvellously learned as The Poseidon Project, the prediction feels well earned. It reads, at the same time, as ironically uncontroversial: if the scholars of the present are at variance respecting the likely fate of this endlessly contentious idea, Bosco leaves those differences aside. Cruise ships, meanwhile, are returning in numbers, as if to remind us that for certain interests, seascapes of lawlessness are still with us after all.

Comments powered by CComment