- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: White space of the unknowable

- Article Subtitle: A daughter’s fragments of memory

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ostensibly, Life with Birds is about the author’s search for her father, a Vietnam War veteran who died when she was young and whose story she hardly knew. As I read it, though, I was reminded of a line from Svetlana Alexievich’s seminal oral history The Unwomanly Face of War (2017): ‘Women’s stories are different and about different things.’ In the end, Life with Birds is less about men and war than about the women left behind – in this case, three daughters and a wife – and the shape of their lives in the wake of his silence, and then his absence.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sarah Gory reviews 'Life with Birds: A suburban lyric' by Bronwyn Rennex

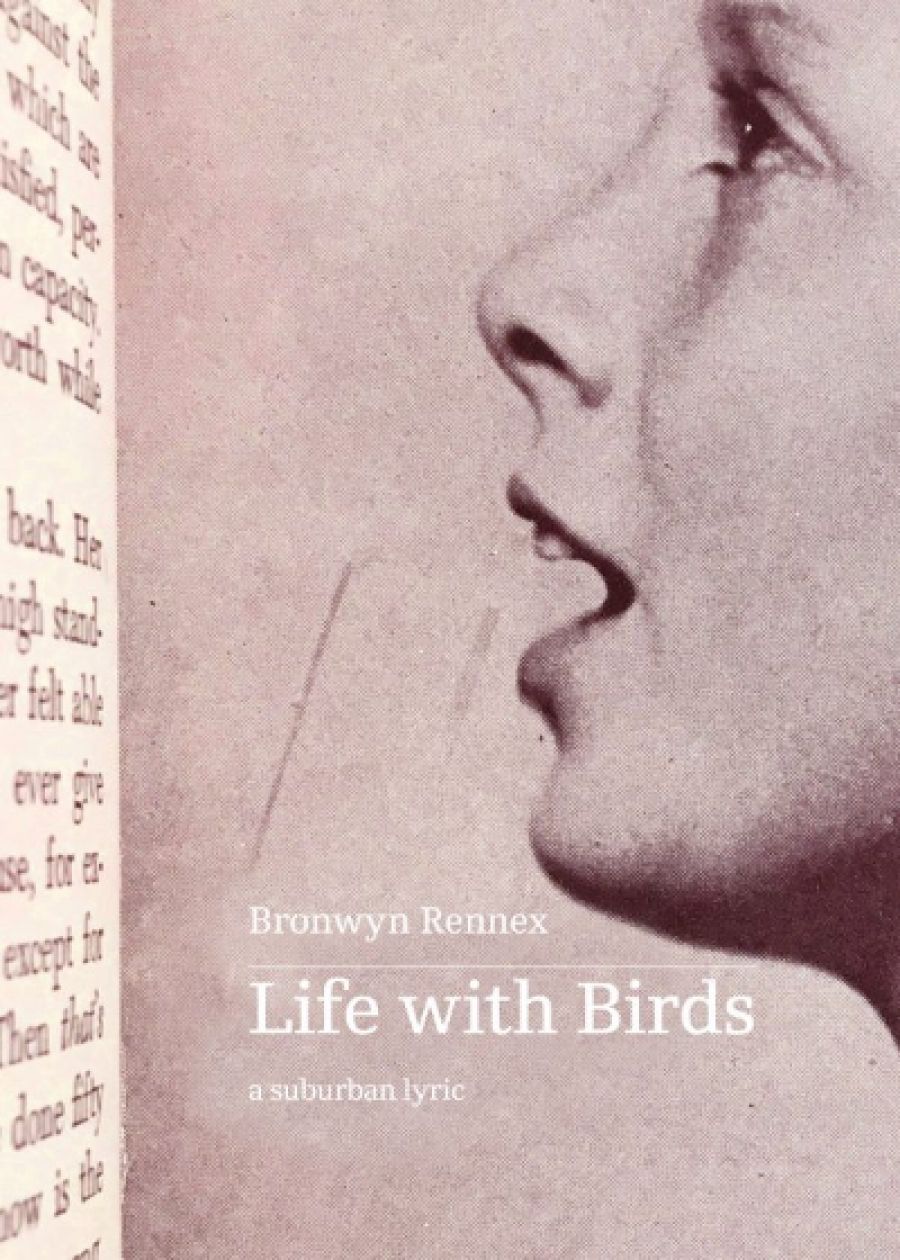

- Book 1 Title: Life with Birds

- Book 1 Subtitle: A suburban lyric

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell, $29.99 pb, 204 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9Ge0x

One of the text’s central questions is whom we are looking for when we delve into the past. Bronwyn Rennex’s father remains almost as obscure to us at the end of the book as he does at the beginning. ‘What am I trying to do?’ she asks. ‘Put bones back into a ghost?’

Life with Birds is haunted by the father, the war, the faceless institutions that govern our lives, but Rennex seems to be piecing together not her father’s life so much as her own memories. She begins, after all, with extracts from her teenage journal. A war story perhaps, inasmuch as it is a reckoning with time and grief and spectral presence.

Yet where her father remains elusive, Rennex draws her suburban home and neighbourhood, and the mother who presided over it all, in sharp detail. This is rendered not through narrative or adjective-laden descriptions, but rather through attention to the quotidian and the specific: the brand of booze her mum would drink in front of the television; the ‘choker of small shells’ Rennex wore to her christening; the various (and varied) pet birds animating the streetscape of her childhood.

Despite the heft of much of the subject matter, Rennex handles the content effortlessly – and not without a certain wry humour. ‘It had never occurred to me before,’ she observes in the midst of a passage about precancerous cells in her ovaries, ‘how much E.T. looks like the female reproductive organs.’ This book is not sentimental, which is not the same thing as saying it is not deeply felt. Take, for example, a recollection of the author and her mother on the Ferris wheel. Moments prior, the mother had critiqued her daughter’s choice of shirt in the hurtful way unique to mothers. Atop the Ferris wheel the wind is strong, and the mother’s wig is dislodged. The daughter sees ‘her straight white undergrowth sticking out around the edges’, and the tenderness is palpable. Rennex’s language throughout is pared back, which helps to ease us into the world she is painting – a world of secrets and backyards and everyday love.

If this is a book about suburbia and family and the way great events play out in our homes and hearts, it is also one about the institutional erasure of the individual. In her attempts to retrieve documents about her father’s war years from various government departments, Rennex encounters a series of Kafkaesque roadblocks. When the requested copy of her mother’s claim for a war widow pension arrives in the post, for instance, half of the letter has been cut off by the photocopier. Apparently, Rennex is told, this is because the letter is foolscap and so cannot fit onto an A4 page. ‘But you can copy it on two pages,’ says Rennex. ‘Am I going mad?’

This bureaucratic web is exemplified in the double-page prose poem of collected acronyms: ‘CWGC Commonwealth War Graves Commission DCO Defence Community Organisation DFISA Defence Force Income Support Allowance’ and so on, and so on. Absurdity yes, but also tragedy – as in the case of Veteran Bird, whose years of requests for support were rejected by the Department of Veterans Affairs because his trauma conditions were not considered ‘permanent and stable’. ‘Jesse’s conditions finally became permanent’, write his parents, ‘when he ended his life’. Resisting the temptation to editorialise or moralise, Rennex tells Bird’s story by reproducing the letters his family wrote to Veteran Affairs.

This same sense of restraint is evident in the text’s composition. Rather than filling in the gaps with narrative, the book is structured through a series of titled fragments comprising prose, poetry, photographs, lists, letters, army records. Just as Rennex uncovers slivers of her father’s past, so the story is told in fragments, a case of content and form mirroring one another. In fragmentary form, what is absent turns out to be just as resonant as what is present – the white space of the unknowable.

Rennex is also an artist and former gallery director, and her eye for visual modes of storytelling comes through in the inclusion of images, rendered in black and white and embedded throughout the text – her father in uniform, family photographs, letters, army records. Uncaptioned, they remind us of the way W.G. Sebald used images in Austerlitz (2001), intrinsic to the story at hand rather than merely illustrative. Interestingly, like Austerlitz, Life with Birds is a haunted text about the messy aftermath of war and the slipperiness of memory.

The final thread running through Life with Birds is, of course, the titular birds. I’m not always certain how they connect to the book at large, other than for the accounting of a life and the strange ways that memories of one thing become entangled with another. And then, in a fragment towards the end, Rennex recounts clearing out the garage after her mother dies and finding a dusty Myna bird that had been trapped there for who knows how long. Perhaps, Rennex thinks, drawing on Irish folklore, the bird was the spirit of her long-dead father, having ‘hung around the tool shed long enough to look after her [mother].’ If Life with Birds is a ghost story, Rennex seems to be telling us that it is a love story too.

Comments powered by CComment