- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fiscal fellow travellers

- Article Subtitle: Abetting Putin and his cronies

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

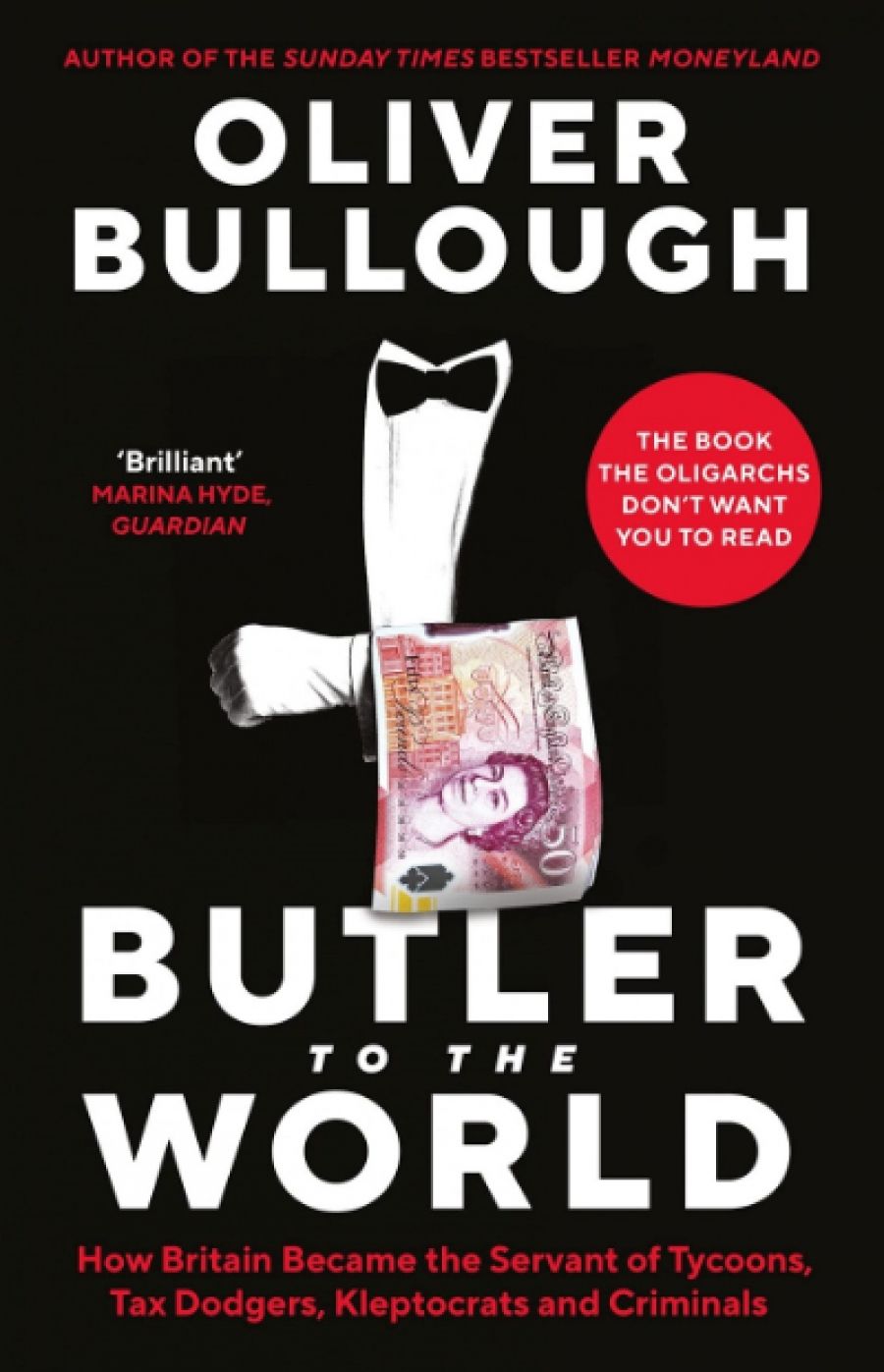

The ongoing war in Ukraine is not mentioned in Oliver Bullough’s new book, Butler to the World. That is not unexpected: it went to press before Russia invaded Ukraine. But Vladimir Putin’s illegal and reprehensible invasion looms large over this excellent new book about Britain’s role in enabling financial crime. The invasion is an acute example of the real-world consequences of this industry.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kieran Pender reviews 'Butler to the World: How Britain became the servant of tycoons, tax dodgers, kleptocrats and criminals' by Oliver Bullough

- Book 1 Title: Butler to the World

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Britain became the servant of tycoons, tax dodgers, kleptocrats and criminals

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $39.99 hb, 273 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/OR06YG

As the author sets out in forensic detail in Butler to the World, bankers, lawyers, accountants, and other professionals in London and Britain’s offshore territories have made it their business to help wealthy individuals manage money and avoid scrutiny – with a blatant disregard for the consequences. They have been active accomplices as Kremlin-loyalist oligarchs accumulated wealth and influence in recent decades, and must now share the culpability. At last, following the war in Ukraine and associated sanctions on oligarchs, a reckoning for these ‘butlers’ has begun. Will it last?

Oliver Bullough (photograph via Twitter)

Oliver Bullough (photograph via Twitter)

Butler to the World begins, somewhat surprisingly, in Egypt in the 1950s. As the sun set on the British empire – underscored by the fiasco that was the Suez crisis of 1956 – Britain searched for a new role in the world. ‘Britain wasn’t the biggest bully in class anymore, but it still knew an awful lot about the bullying business, and that knowledge turned out to be very valuable indeed,’ Bullough writes. That role was helping the wealthy, regardless of the provenance of the wealth. Bullough frequently returns to the most famous caricature of a butler – Jeeves in P.G. Wodehouse’s stories – as an effective shorthand for the role British bankers, lawyers, and accountants play today.

From the Suez, Bullough travels (metaphorically, for much of the book was written during lockdown) to London as the City’s financial sector invented the ‘eurodollar’ (US dollars held offshore to avoid regulation), and on to Tanzania, the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Moldova, Scotland, Kazakhstan, and beyond. He relates how legal quirks have been exploited to enable money laundering and to hide dubious wealth, and how British professionals have been all too happy to assist, with regulators largely turning a blind eye. Bullough tells the story of the BVI’s emergence as an accidental tax haven and shell company paradise, after an American lawyer came calling in the 1970s. He goes on the trail of a billion dollars that went missing from Moldova, one of the poorest countries in Europe, thanks to an opaque legal form, a Scottish Limited Partnership.

One of the strengths of Butler to the World is that Bullough never loses sight of the human cost of this industry. One particularly illuminating chapter describes how Gibraltar, the British territory on the edge of Spain, was instrumental in the proliferation of the gambling industry by undercutting other jurisdictions on taxes and regulation. Britain’s betting problem – currently estimated at more than $200 billion annually, and leading to about 650 addiction-related suicides each year – began in Gibraltar. ‘Just as the BVI feels divorced from the reality of how its shell companies allow kleptocrats to hide their crimes and wealth companies to reduce their taxes to nothing, Gibraltar is a world away from the reality of young people spending money they don’t have on online games rigged to ensure they can’t win,’ he writes. A world away in the minds of the butlers, perhaps, but having devastating real-world consequences nonetheless.

Bullough began his career as a foreign correspondent in Russia, reporting on the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union, including the war in Chechnya. His first two books covered this ground: Let Our Fame Be Great (2010), about culture and conflict in the Caucasus, and The Last Man in Russia (2013), on the decline of Russian society. Bullough has since become an expert on financial crime – Butler to the World follows his book Moneyland (which I reviewed in the May 2019 issue of ABR). But the writer’s knowledge of the post-Soviet world, and his journalistic eye for a narrative, help ensure that his work is eminently readable, despite the complexity of the subject matter.

If there is a flaw in this otherwise excellent book, it is that Bullough fails to fully interrogate the role of lawyers and the British legal system in assisting foreigners to protect their wealth and reputation. One of the final chapters does explore the rise of private prosecutions, a peculiarity of the British justice system. But Bullough neglects to canvass in any depth how libel proceedings have become a favoured tool deployed by oligarchs to keep investigative journalists at bay. It is a perplexing omission, given that Bullough himself is currently faced with a costly defamation claim brought by the vice-president of Angola over his last book (albeit in Portugal, rather than the English courts).

Fortunately, the war in Ukraine has focused Britain’s attention on the misuse of libel law to silence journalism, a ploy that has been labelled ‘strategic litigation against public participation’ (SLAPP) cases. When distinguished journalist Catherine Belton published a book on Putin and his allies, Putin’s People (2020), her publisher was promptly sued by four oligarchs and a major Russian oil company. Since the invasion, three of the four oligarchs have been sanctioned by the United Kingdom for their ties to Putin. The House of Commons is belatedly investigating such ‘lawfare’.

While Butler to the World is largely focused on Britain’s woes, it offers salutary lessons for other jurisdictions, Australia included. We should not be so naïve as to presume that none of the factors that have allowed the ‘tycoons, tax dodgers, kleptocrats and criminals’ of Bullough’s subtitle to subvert the British system is present here, even if the problem might not be so acute – yet. Australia’s domestic and offshore anti-bribery and corruption laws have been criticised for their shortcomings. In 2015, the Financial Action Task Force, an international body, called out Australia for failing to apply anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financial laws to professional services, including lawyers, accountants, real estate agents, and trust and company service providers. Seven years later, there has been no action. Australia now joins Haiti and Madagascar as the only three nations yet to even begin the process. In June 2022, The Sydney Morning Herald published an article headlined ‘From Casinos to Houses: Why Australia Remains a Money Laundering Haven’.

The reputation management offered by British lawyers is also increasingly influencing the Australian approach to defamation; Roman Abramovich, a now-sanctioned Russian oligarch, sued Belton’s British publisher in Australia’s Federal Court in 2021, in parallel with the London proceedings (both cases were ultimately settled). If Australia does not presently serve as the butler depicted by Bullough, this is largely by accident rather than design.

Butler to the World is a timely and penetrating work of investigative journalism. Bullough diagnoses the ills that have allowed Britain to become the go-to destination when ‘dictators want somewhere to hide their money’ or ‘oligarchs want someone to launder their reputation’. In effect, Bullough is holding up a mirror to Britain’s professional services class.

The trade may be lucrative, but is the human cost worth it, he asks. Russia’s bloody invasion of Ukraine – well past the 100-day mark, with no end in sight – is a tragic reminder of the high cost of aiding and abetting corruption.

Comments powered by CComment