- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: On the precipice

- Article Subtitle: Adam Ouston’s Bernhardian début

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1908, on 11 September (an ominous day for the changing nature of planes in our dreams), Franz Kafka and Max Brod travelled to Brescia in Italy to watch Louis Blériot fly a plane. For Kafka, and probably most in the crowd, this was the first opportunity to witness a human crawl into a machine and, like something out of Greek Myth, fly towards the Mediterranean sun. Kafka and Brod decided to record their observations. Brod saw the pilot draw inspiration from the adoring crowd. Blériot ‘was being lifted on high by the mounting murmur of the thousands’. Kafka, sensing the crowd’s devoted gaze, had a different impression, ‘twenty meters above the earth a person is trapped in a wooden construction, fighting a voluntary and invisible danger. And we are down here, crowded and insubstantial, watching.’

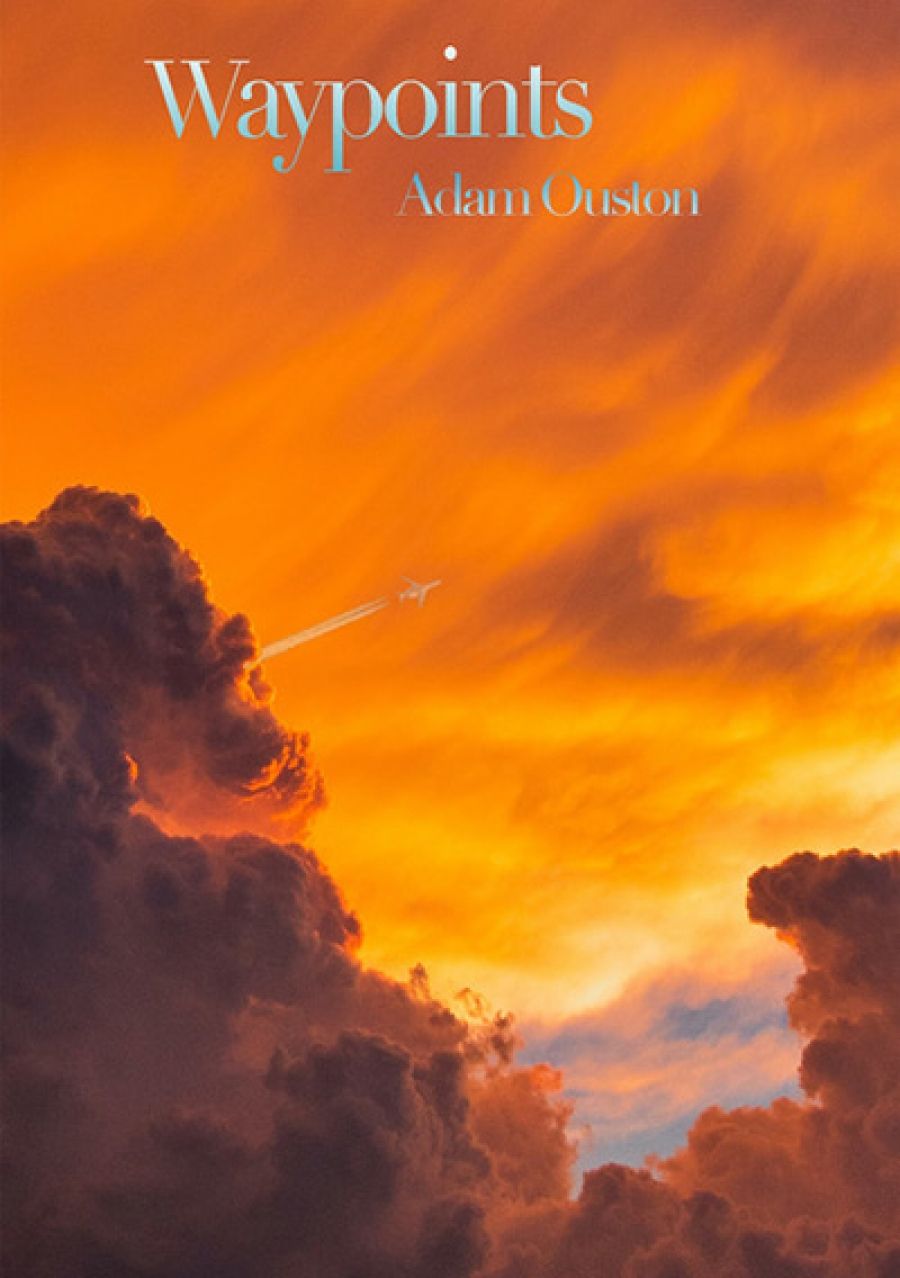

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Cover of Adam Ouston's Waypoints

- Book 1 Title: Waypoints

- Book 1 Biblio: Splice, $ 29.95 pb, 173 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4e0693

Blériot was soaring into freedom while trapped in a prison of his own making, as if Jesus had been made to build his own cross. At Brescia, the planes never arose high enough to escape the crowds’ adoring eyes. The viewers could hear the engine and the spinning propellers (to Kafka they sounded ‘something like snoring’), the jutting of engines, and the thud of the plane’s bicycle wheels as it trundled along the rudimentary runway. The spectators needed Blériot, and he needed their adoration to take off. We can see the presence of enchantment between crowd, pilot, and technology during aviation’s nascent years. Adam Ouston, in his first novel, Waypoints, rediscovers this magic and charts its demise to passengers in the twenty-first century flying not with this sense of possibility and freedom, but packed together in, what is commonly called, cattle class.

Adam Ouston’s achievements in this novel are significant. He has built a plane out of Australian historical fiction, filled the tank with a few gallons of Thomas Bernhard and W.G. Sebald, spun the propeller, and taken off. He bases Waypoints on Harry Houdini’s flight above a Melbourne field in 1910. One can imagine Houdini flying high above the Australian crowds, a pioneer of the air, with no final destination, just wanting to excite the crowd.

In Waypoints, Ouston employs a Bernhardian narrator to eschew the fidelity that a realist narrative would require and achieve a narrator that will ‘[i]n the twentieth century, turn into a time machine, which would, sorry to say dear Harrys, render me – Bernard to those who know me – the first man to travel back in time and defeat the Great Houdini’. Ouston writes rich parataxis sentences that combine sensory impressions with the detritus of history, like a jazz musician twinning together disparate chords into a late-night jam. For Bernard’s wife and child both died on board Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370. This trauma is encoded in the novel’s manic tone. Bernard is losing it. How could such a huge flight just disappear? All he is left with is a sense of numbness and he wants to enter ‘a time in which a miracle was a machine getting up, up, into the air as opposed to vanishing completely from it.’ Most planes have a final destination. MH370 never arrived anywhere. Into this gaping void conspiracy theories rush. Bernard goes through the various interpretations of what happened to MH370 and the details further derange him. An unscheduled waypoint took his family from him. For on a long journey waypoints are the way of the dérive, the flâneur, the hobo, the orphans, the prison break, the somnambulist, and the unaccountably lost plane.

Bernard wants closure. He wants to know what became of his family. The contradiction is that in the age of the internet, with a saturation of information, there is very little data on MH370. The novel repeats the line ‘every fact, datum, or titbit literally at our fingertips’ as a common refrain. But there is no hard data to explain what become of his family. He wants an explanation, but without any news about what occurred, his thinking only induces vertigo. What Ouston is writing about is this loss of magic in our world. We can chart its bristling presence in Houdini’s flight to its lackadaisical and pejorative lingering hum in the disappearance of MH370. Here lies Ouston’s contribution to Australian literature. He is practising a new way of writing within the contested space of Australian historical fiction. After all, the original Australian historical fiction was the grand narrative of terra nullius, grafted onto the land like an ill-fitting suit. It is not these grand narratives but the minor details that individuals use to illuminate their own place within history. Bernard is trying to deal with his trauma by recreating Houdini’s flight. Bernard must ‘get my imagination going, soaring in fact, and looking down at my aviation suit, my shirt and tie, the thick (almost blinding, it must be said) rims of my old aviator goggles, the smells and sounds of the motor, I am thrust back into that time of pioneers, I am standing on the precipice of the twentieth century.’

Another writer who was obsessed with flying, the Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro, once wrote that in the future poems would be written in airplane language and we would all inhabit a ‘beautiful madness in the zone of language’. Waypoints by Adam Ouston is this beautiful madness.

Comments powered by CComment