- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Itchy feet

- Article Subtitle: New poetry from Alison Flett and Hazel Smith

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

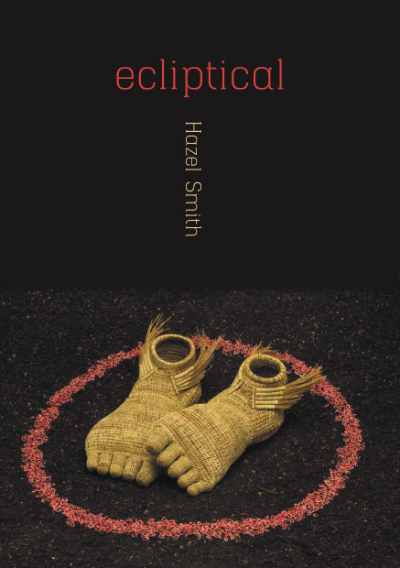

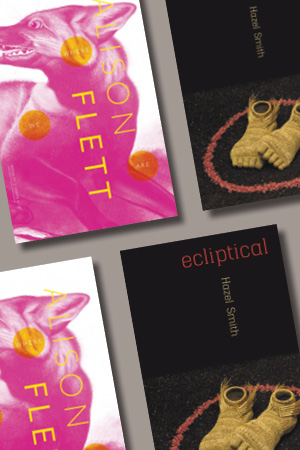

Hazel Smith’s ecliptical features an image of a Sieglinde Karl-Spence work of art, ‘Becoming’, a pair of ‘winged feet woven with allocasuarina needles’. It is a striking image, evocative of Mercury, with one foot resting on the other, as if the right foot’s instep is itchy. The idea of ‘itchy feet’ is something that ties ecliptical to Alison Flett’s Where We Are. Flett and Smith are both migrants to Australia; their poetry is sensitive to its site of writing, and to international and interpersonal connections.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Chris Arnold reviews 'Where We Are' by Alison Flett and 'ecliptical' by Hazel Smith

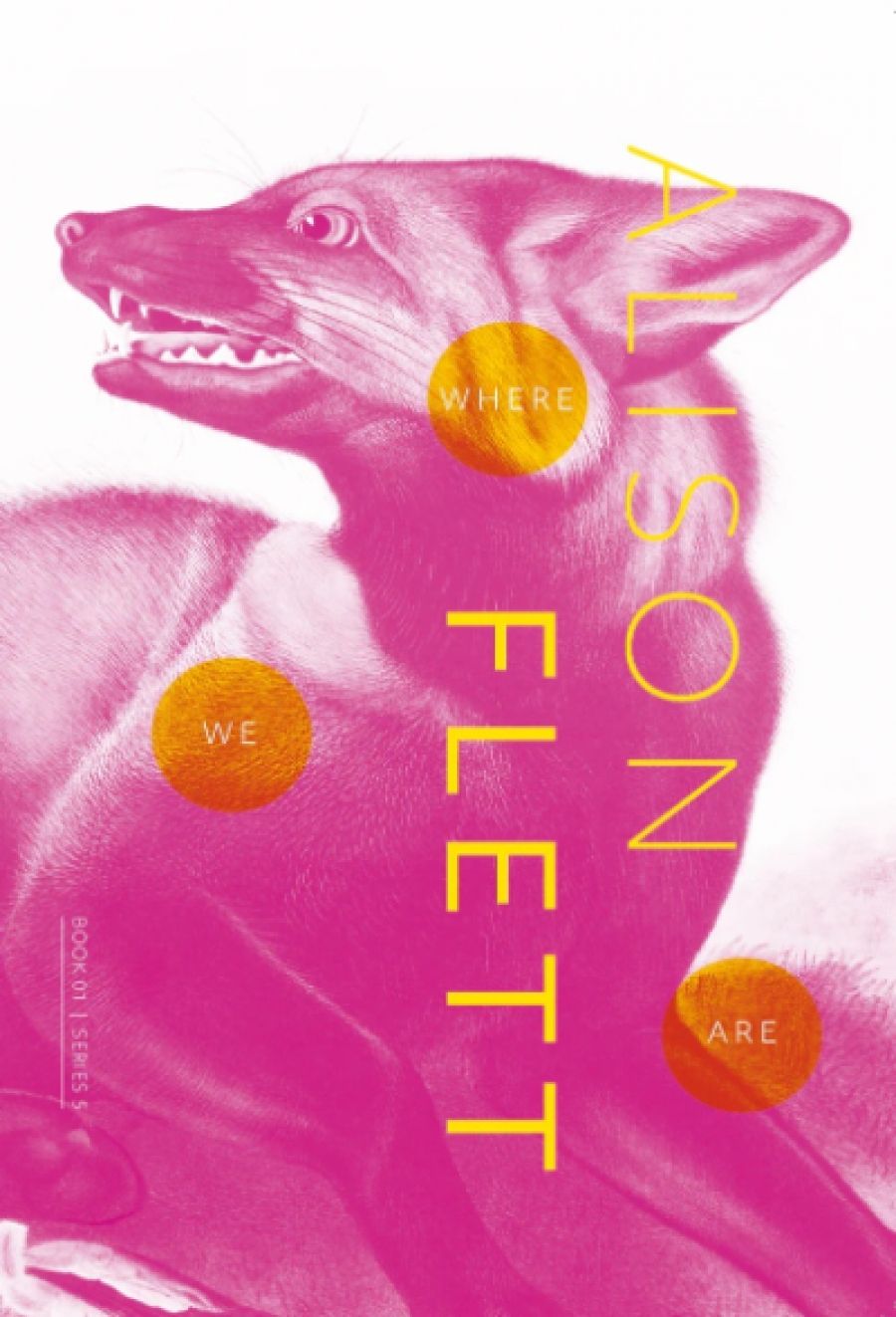

- Book 1 Title: Where We Are

- Book 1 Biblio: Cordite Books, $20 pb, 73 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPBj0Y

- Book 2 Title: ecliptical

- Book 2 Biblio: Spineless Wonders, $24.95 pb, 137 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/July_2022/META/ecliptical.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qn9QWL

Then there are the poems that ask more of the reader. ‘Rank-A-Poem’ is a remarkably well-executed survey-as-poem. The brutally short sentences in ‘Firebrand’ evoke bushfire: ‘Bodies cruciform on beaches. Day posing as night. The po-faced fire app. Warming the backs of his legs.’ ecliptical also works with the ‘posthuman’, through several machine-assisted poems. Machine assistance is provided courtesy of Roger Dean, Smith’s partner and collaborator in AustraLYSIS, an electro-acoustic music collective headed by Smith and Dean. Dean has a background in cognitive science, and ecliptical shows evidence of a deep awareness of how memory works. Common experience has memory functioning like a bank of videos we ‘play back’, but neuroscience shows that memories are rebuilt from fragments rather than remembered as units. Memory is unreliable, mutable stuff. Smith gives this thinking as the basis for ecliptical’s title: memory is circuitous and easily overshadowed. There is a hint of Ern Malley’s The Darkening Ecliptic. Smith claims that Malley had no influence on the collection or its title, so it seems that Ern’s ghost works in mysterious ways: ecliptical probes deeply into questions of authenticity and identity. Perhaps that’s inevitable in poetry that questions memory, whether it’s the textual memory of Ern Malley’s collage poems, or physical memory.

Questions of authenticity and identity are obvious in ‘The Lips are Different’. They’re less explicit elsewhere, but always present.

ecliptical’s opening poem, ‘The Collection’, takes this questioning to its logical conclusion:

an overarching theme

with moat-like fencing

was fashionable

but she wanted to

spit out

the volume in little bits

Read as a manifesto for the collection, this poem denies the book any fixed message or style. ecliptical works more like memory; its identity builds from ‘little bits’.

Sound is crucial to ecliptical’s strength, and to Alison Flett’s Where We Are. Flett’s Scottish background is prominent in poems such as ‘No Matter What’: ‘today ahm alive, taes / pointin taewards / ooter space’. Poems such as this are occasional reminders that the reader is in a different sonic space. My internal Scottish accent is dreadful, but reading with a different cadence in mind reveals poetry with a finely tuned rhythm.

At times Where We Are overdoes the self-reflexive poem. A clutch of these near the middle of the book have the poet writing herself writing the poem. ‘No Alarms and No Surprises’, for example, seems to betray hesitancy, as if the poet has nothing much to say, though the poem contradicts this, abruptly moving from ‘I wrote this poem / someone used the atm’, to a thought that slides everything to a different scale:

all-the-time underground trillions

of chemolithitrophs are thriving without light

eating only stone

The poem pulls up short just as it gets going:

what’s that got to do with anything?

nothing just me

skrauching across the abyss

Perhaps this hesitation reflects the insecurity that goes with meeting new people, with trying to find a place and a community.

Whatever the case, Where We Are rewards persistence. ‘No Alarms and No Surprises’ marks something of a turning point. From there, the poetry’s like the fox on the cover: sure-footed and purposeful. This is particularly evident in the longer poems. A six-part sequence, ‘Semiosphere’, is a formally variable meditation on the fox as a symbol for the wild’s coexistence with the domestic. Part three, ‘Liminoid’, is a short prose story of finding the sublime in an urban encounter with a fox – ‘a pencil line o silens runnin atween me an the fox’. Part five, ‘Parousia-apousia’, combines familiar phrasing with scientific language – ‘you solve me fox, you straighten my gaze / push your bright dark neb through my CNS’. Other long poems, ‘Seen Through’ and ‘Vessel’, are no less effective. ‘Cemetery Songs’ is an understated concrete poem; a monumental garden of pathways, stairways, and slabs of text.

The tension between wildness and domesticity is a theme that Flett signals in her preface, writing of a ‘bone-dry and primal’ longing for her home and people. It’s a motif she taps for ecological thinking, from the empathetic pain of ‘Connections’ to the antipodal shock of the upside-down seasons. ‘Wrong Season Christmas’ is particularly affecting, beginning with ‘Almost a fortnight over 40’ and the lit Christmas tree overshadowed by lit trees in the bush.

the smell of burning gum

glistering embers of gold

the giant fires that birl inside.

All that wrapped stuff

in the corner

turns quietly invisible.

Whether it’s bushfire, a daughter hanging out the washing, or a kitchen door – ‘rain has pixelated the flyscreen’ – Flett’s observations of nature against human life are incisive.

At a recent publisher’s event, the question of Hazel Smith’s place in Australian poetry was raised. I imagine it’s a question that vexes any migrant writer, and it’s encouraging that Smith and Flett each find different ways of speaking to and of Australia and its literature. Both are confident in the value of diasporic voices; their different points of view and their different sound. Two references encapsulate the musicality of these collections: Flett’s John Coltrane/Neil Armstrong mash-up from ‘Ars Poetica in the Outback’ – ‘The moon’s theme tune / plays but there are no giant steps.’ – and Hazel Smith’s ‘Listening’ – ‘There was […] no law about how to open your ears.’

Comments powered by CComment