- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Heels on the throat of song

- Article Subtitle: Exploring the limits of poetry’s expressivity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of Marion May Campbell’s third poetry collection, languish, conjures ideas of laziness, daydream, failure to make progress, ennui, lack of enthusiasm, anhedonia. Campbell’s poetry is concerned with the excitement of language, but also its debasement. Several reviewers have commented on the work’s intertextuality (Campbell often employs compositional strategies such as parody, allusion, calque). Always the audience or reader is integral to shaping the text. For Campbell, importantly, the unsaid or unquestioned are as important as collaged lyric or contemporary language trace, as seen in these lines from the first poem in the collection, ‘speechless’:

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jennifer Harrison reviews 'languish' by Marion May Campbell and 'And to Ecstasy' by Marjon Mossammaparast

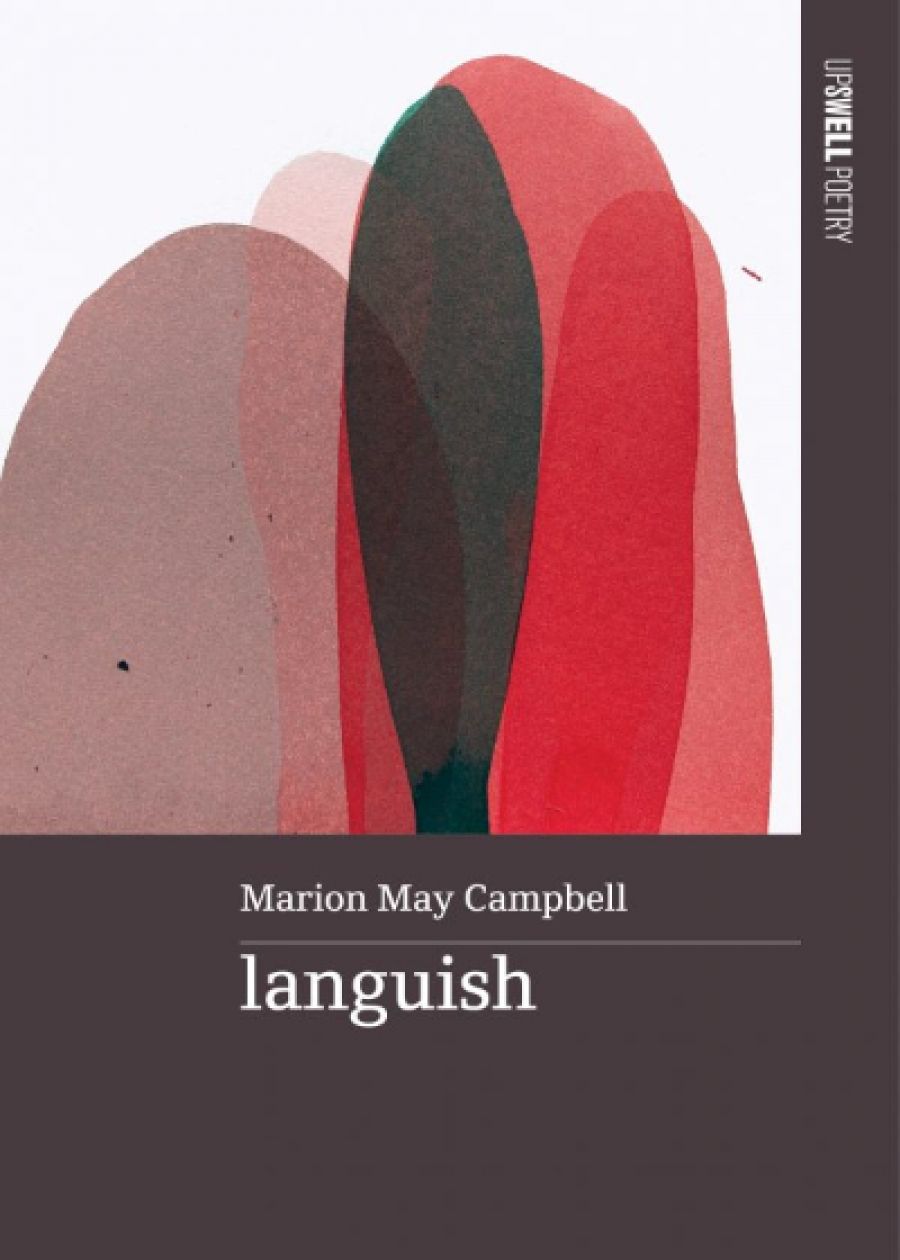

- Book 1 Title: languish

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell Publishing, $24 pb, 103 pp

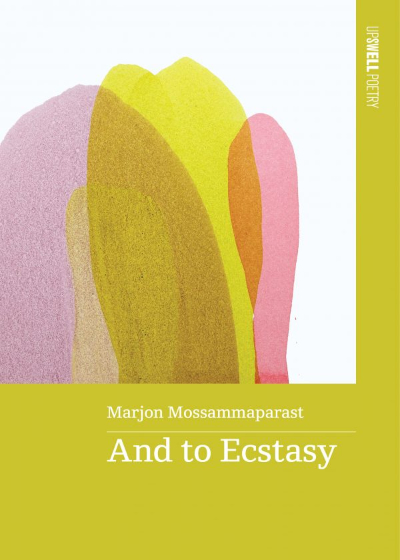

- Book 2 Title: And to Ecstasy

- Book 2 Biblio: Upswell Publishing, $24.99 pb, 88 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/July_2022/META/And to Ecstasy.jpg

From the same poem, later lines suggest the poet’s task is: ‘to break / this isolation of wounded consciousness / whose claim to suffer cannot reach / the billion lives that we detain / in the tropic margins of our precious / speechlessness’. In political terms, this poem appears to challenge language’s failures. The enjambments are untraditional, almost careless, yet urgent. All this in the first poem of a section titled ‘our heels on the throat of their song’, a phrase which references Vladimir Mayakovsky’s futurism, his challenge to conservatism and interest in cultural renewal.

This initial poem is also described as a response to Nathalie Sarraute’s 1939 experimental novel Tropisms (to quote Campbell’s notes: the novel is about ‘the interior movements that precede and prepare our words and actions’). In psychology, the term references the way individuals acquire new functions through experience, and underpins stimulus-response theory like that outlined in The Psychology of B. F. Skinner. The questions posed by such a charting of language dynamics are those of interiority, subjectivity, but also the microscopic psychological ramifications of cause and effect. In Campbell’s crisp, excoriating, often witty poems, the antidote to languishing is exactly the Mayakovskian of forging modern subjectivity in art: a cultural renewal that doesn’t flinch from sharp self-critique in the context of what has been inherited in terms of utterance.

The prose poems are extraordinary creatures (or, as the poet Philip Salom calls them, ‘lyrically trippy and beguiling’). Whether exploring language as aquifer soaking up meaning (‘Eurydice & the frogs’) or the ‘tick-tick-tick’ of impending mortality (‘breakdown’), they dazzle with manoeuvres, wit, textures. In the ‘settle of brittle’ of a poem like ‘still life’, the ravaged earth is sardonically idyllically female, yet physically mined: ‘my bifurcated self cracked up in mourning for this gone / gone land, where littered bones of sonnets, bones of lyrics lie where / the epic petered out, staggered into the blaze, went mad.’ The poem ends, ‘Where there is still life, there still is life. They’ll see. Or not. It is / precisely, finally, equivalent.’ My margin note calls this poem brilliant. Its rage against ‘the edicts’, its rave against silence and personal inaction, its embrace of human frailty is full of savagery. A prose poem later in the collection, ‘stabat mater’ (a term which references the suffering of the Virgin Mary on her son’s crucifixion) imagines how we might begin again to fashion a new Venus of Willendorf, a new vessel of language that is free from bias and insinuation: ‘from the dream yeast she rises’.

The final section of the book, ‘in the margins of desire’, explores the intimacy of relationships. The personal is not for languishing within sentimentally. Pronouns are vivisected until they dissolve, ‘It’s like a pronoun for the self-diminished, a marker for all the proper names retreated. The greedy amnestic dark’ (‘pronouns in the darker mirror’). The poems seethe with sensuality, oscillating between unreality where loss of love is like ‘sailing a dream, a ship without mast or compass’ and shocked pragmatism, ‘a Bunnings drill without a cord ... cordlessly I am charged / by that drill / to return to primal words’ (‘cleaving, or, rereading difference & other distractions during this time of plague’). The final, rather beautiful prose poem in the collection, ‘in the next paragraph’, invokes ‘the declivity between dunes where ‘we dreamed riparian, and flowed back in.’ Dream imagery might impress as the easiest trope of this magical collection and yet the dream of wetlands, the laws of living by water, suffuse any dream’s idyll with the reality of water – like language, it flows on if let be.

Marjon Mossammaparast’s earlier book, That Sight, won the 2018 Mary Gilmore award and was commended in several other awards. I was impressed by the way these new poems reach into spiritual traditions, such as that of the Bahá’í faith, yet also explore identity. This anchoring within worldly place (many poems footnote a particular place of action at the end of the poem) allows the poems their own meditative inspiration that sites experience at the centre of the poem, or at least signs off with ‘place’ as the poem’s postscript. Actuality of place seems to be almost an afterthought, a punctuation of memory.

Mossammaparast’s elegant poems create a whole from fragments of text and glimpses of meaning, reminding me of Anne Carson’s explorations of archaic fragments. Antiquity is a presence here but in no way overpowers the sense of a contemporary observant intelligence. Cultural record is presented with grace. One might choose any poem to quote, but here is ‘Interlude 3’ from the section ‘(Here)’ in entirety:

This afternoon moorhens, scratching in the leaves colossal humus

pelican and ibis, the tune of honeysuckle underfoot

electricity towers’ unbroken Morse

the limbic pose of a submerged log and Time, percolating

at the bottom of the lake, to date later to testify

Jells Park

Not exactly puzzle boxes, yet always mysteriously eloquent, the poems circle around certainty, creating eddies of meaning, a different kind of dream from Campbell’s: a metaphysical dreamfield in which the reader contemplates their own surroundings, questioning the way meaning is made, the scale of signification. The poetry seems minimalistic (the contents page lists only the three sections of the collection – ‘(There)’, ‘(Here)’ and ‘Field’) – but Mossammaparast’s simplicity is deceptively complex. The poems are layered with space, pause, and non-sequiturs that move in surprising ways, ‘light / The long pause, fretful and laden. / We are prone.’ (‘Interlude 2’).

References range from an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Farsi script, the poem ‘Seeing Things’ by Seamus Heaney, and Cai Guo-Chiang’s Terracotta Warriors. Punctuation is both formal and informal, and the poems embrace expansive imagery without compromising tautness. The impression is one of careful thought and text ‘placement’ as though every nuance matters. In the collection’s final section, Mossammaparast fashions a unique spiritual field from lines that travel between cosmos and grass, ‘in a field neither here nor there / where created things are / and absolutes concealed / planes, rolled up in plains / hiding the stem of the leaf / we climb and climb (‘Cosmos’).

The oscillation between small and large, grass and cosmos, space and particularity affords this poetry a perspective that is both beautiful and challenging. From poems that reference Sufi cosmology to a poem fashioned from the Islamic 99 Names of God in Arabic, this work impresses as a poetry of integration as well as scale.

In their awareness and acknowledgment of past writers and thinkers, Marion May Campbell and Marjon Mossammaparast appear to have similar preoccupations. Perhaps it is this depth of interrogation, as well as the finesse of the poetry, that Upswell finds deeply important. This is poetry of belonging, dislocation, and location. These two books are voiced so differently, yet both exude assurance, uncertainty, a belief in poetry’s centrality to cultural thought and definition. Where poetry directs language, we look and listen: ‘they warp and weft just to say I am’ (‘winds’). g

Comments powered by CComment