- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Might be long long time’

- Article Subtitle: A mixed anthology of trans-Tasman poetry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There’s an old Irish saying: ‘If you want praise, die. If you want blame, marry.’ I could add from personal experience, ‘If you really want blame, edit a poetry anthology.’ While poetry is relatively popular, it often seems that more people write it than read it. As a result, poets can be desperate for affirmation and recognition, managing their careers more jealously than investment bankers. What too often gets lost in all the log-rolling and back-scratching is the poetry. We turn to anthologies for help, hoping to find in small, palatable doses good poets we can choose to read in depth. We find anthologies representing nations or geographical regions, literary periods, ethnicities, genders and sexual orientations, forms, categories like postmodernism, post-colonialism, eco-poetry, and themes like love or madness.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Mason reviews 'The Language in My Tongue: An anthology of Australian and New Zealand poetry' edited by Cassandra Atherton and Paul Hetherington

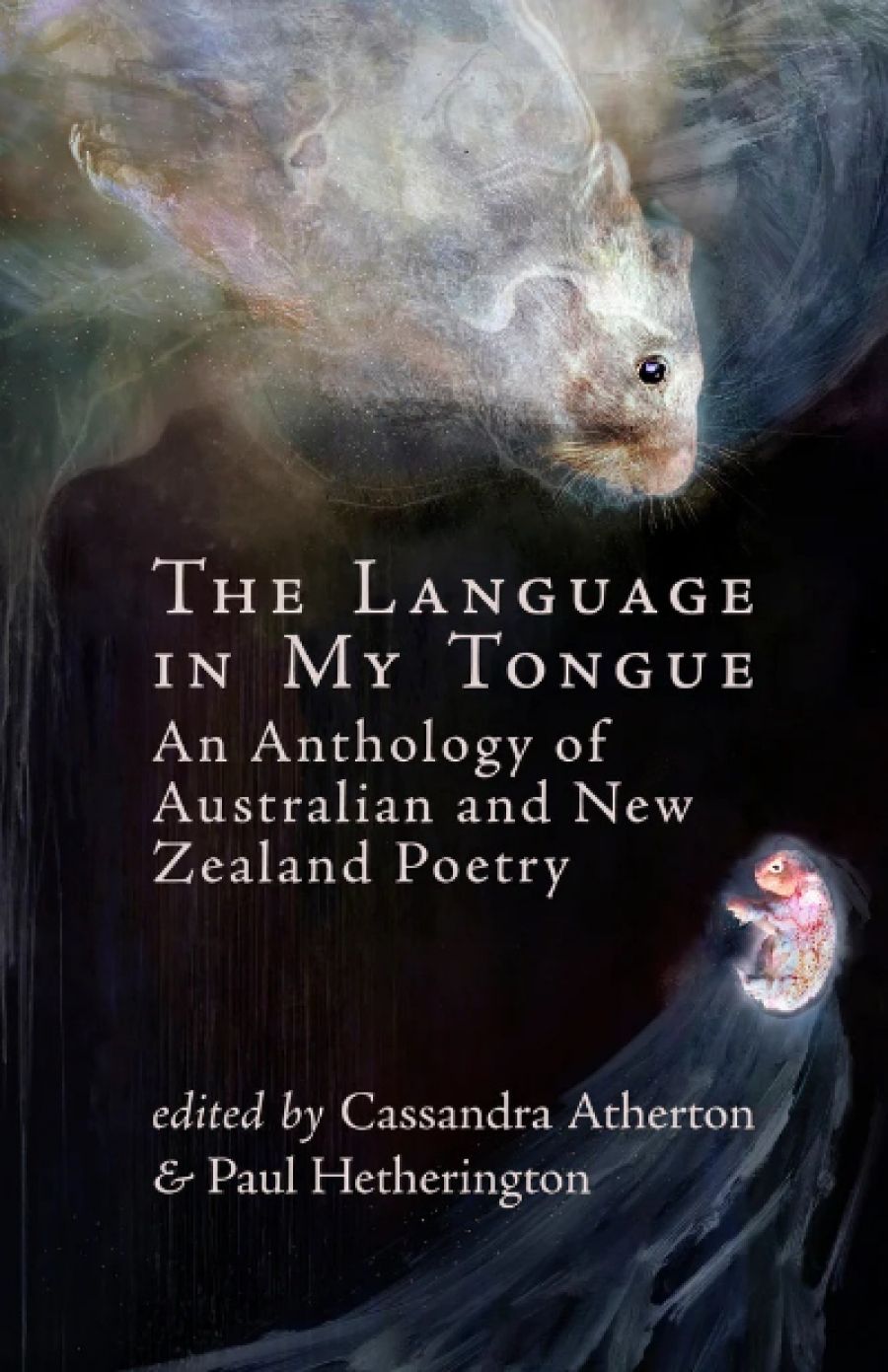

- Book 1 Title: The Language in My Tongue

- Book 1 Subtitle: An anthology of Australian and New Zealand poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: FarFlung Editions, US$21.95 pb, 215 pp

The Language in My Tongue, edited by Cassandra Atherton and Paul Hetherington, is hard to pin down. You could call it a regional anthology, its thirty-five poets coming from Australia and New Zealand. It is relatively brief, which can be welcoming, but I am not always convinced it contains the best work these poets have to offer. The editors strive to make a case for poetry as resistance – what Wallace Stevens elegantly called ‘the imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality’. Much of their rationale is salutary, but when their introduction descends to academic clichés I instinctively revolt: ‘many of the poems in this volume are haunted by the liminal spaces of demotic intimacy and alienation. They explore a relationship with the quotidian which engages with concepts of transgressive intensity and self-reflexive technique.’ Yuck. What about making poems we can dwell in as well as dwell upon?

When the poems in this volume fall flat, as several do, they seem afraid of eloquence. I feel a bit unfair picking on Adam Aitken, whose poems open the book by virtue of alphabetical order, but his lines too often forgo the poet’s brief in favour of triviality: ‘Reaching forty now I ask: Why did Mum / never sew the hems of my jeans, even if Death on the TV / reminded her of her children?’ When Aitken casts lines aside and gives us a prose poem, calling it ‘Lines from The Lover’, the most beautiful bit is a quotation from Marguerite Duras. Prose poems require a rare talent for poetic experience minus poetry’s most distinctive element, the line. Those on offer by Luke Beesley, for example, are clever but cold. If I compare Beesley’s ‘Bees Nudge the Mouth of a Feathered Rose’ to the psychological nuance of ‘A Story About the Body’, by Robert Hass, I find the latter, which far more stingingly involves bees, a poem I can’t forget, Beesley’s a poem I can’t remember.

I am more intrigued by the outright experiments of the late Jordie Albiston, who combined the conceptual audacity of the avant-garde with a beautiful way of phrasing emotional states:

… to enter the error is recklessness

to feel it deeply austere absolute

it is sent to murder us in our sleep

it is a bitmap of all that I am

what can be learned from the rickety mind

what can be learned from a glittering shape

– children & gods beseech our instruction

Albiston at her best offered such beauty that her untimely death earlier this year seems a loss, among all the other losses, to modern poetry.

Editors of anthologies make a perilous choice when they include examples of their own work. I was entertained by the playful free associations in the first two prose poems by Cassandra Atherton, but more powerfully impressed by her ‘Relics of Hiroshima’:

Time is like a keloid that keeps returning. Black rain stripes white walls in inky watercolour. We see twisted metal and debris, a stack of fused teacups – fragments of lives that persevere. The hibakusha sobs as he holds up his sister’s school shirt. It trembles like a flag.

By contrast, Paul Hetherington’s prose here – admittedly an excerpt from a longer work – feels at times like an essay in art criticism. His verse in ‘September’ moves me more. So what is one to think of any poet’s work known only by such selections? We can understand why some poems, and not always good ones, become anthology pieces, perennial favourites, but The Language in My Tongue is not that kind of anthology, not a book of touchstones or chestnuts. Readers will identify their own preferences and I can only be honest about mine. I find some of this writing enervated, anxious, and dull.

I admired the post-colonial clarity of Merlinda Bobis’s ‘The String of Beads’, the graceful ekphrastic of Peter Boyle’s ‘A Painting in the Prado’, and the way Kevin Brophy’s poems express moral urgency without sanctimony. His ‘Dog on the Road’ joins my small anthology of compelling prose poems: ‘Inside you is a world where lives come and go like days, like wrappers, like novels, like meals, like buses, like birds, like seasons, like you. What is love without indifference, you say to yourself.’ The ambiguity of that final sentence stays with me, a signal intelligence.

Several poets here prove adept at rhyme, like Luke Davies – better known, perhaps, as a screenwriter. I want to read more of him, and I want to read more of Ali Cobby Eckermann, who produces lovely dialect writing:

When you feel the story

You know it true

Tell every little story

When the people was alive

Tell every little story more

Might be one week now

Might be long long time

The anthology’s title comes from a prophetic poem by Susan Hawthorne: ‘The language in my body and in my tongue / is the language they spoke in Delphi.’ In contrast, John Tranter’s musings about Australian identity, wishing he were a part of some other culture, seem old hat. They meet a tenable riposte in New Zealander Chris Tse, who writes of ‘Wellington, where the storm can’t take my tongue’.

The poets I like most in this book are unafraid of beauty and eloquence. In addition to some already mentioned I would include Sarah Holland-Batt, Felicity Plunkett, essa may ranapiri, Peter Rose, and Gregory O’Brien, who writes in an elegy for a musician, ‘It was air that gave the grand thing / life. Like a sailboat // or newborn, it was sprung / to song …’ Notice that first line break isolating the word ‘life’. Then you read the second line as ‘life like a sailboat’, followed by a newborn, followed by song. The poem builds with deliberate skill and grace, and I am glad this uneven anthology offered it to us.

Comments powered by CComment