- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Hold on, I’m comin’!’

- Article Subtitle: Novelty and recurrence in Ocean Vuong

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Every time I open Ocean Vuong’s Time Is a Mother, that Sam & Dave lyric ‘Hold on, I’m comin’!’, pops into my head. Is it ars poetica? Hold on: language, arranged in a holding way, might help us manage loss, though no hold will forestall it. I’m coming: the radical presence of the poetic speaker, whose ecstatic ‘now’ of speech exists in strange tension with the past, a thing lost, that full and irretrievable ‘then’. Anne Carson has written memorably of the strange telescoping of now and then in lyric poetry. This is the dilemma of the poet–lover: ‘pinned in an impossible double bind, victim of novelty and recurrence at once.’ Or, as Vuong puts it, ‘[t]he way Lil Peep says I’ll be back in the mornin’ when you know how it ends.’

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Ocean Vuong (photograph by Tom Hines/Penguin Random House)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Ocean Vuong (photograph by Tom Hines/Penguin Random House)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lucy Van reviews 'Time Is a Mother' by Ocean Vuong

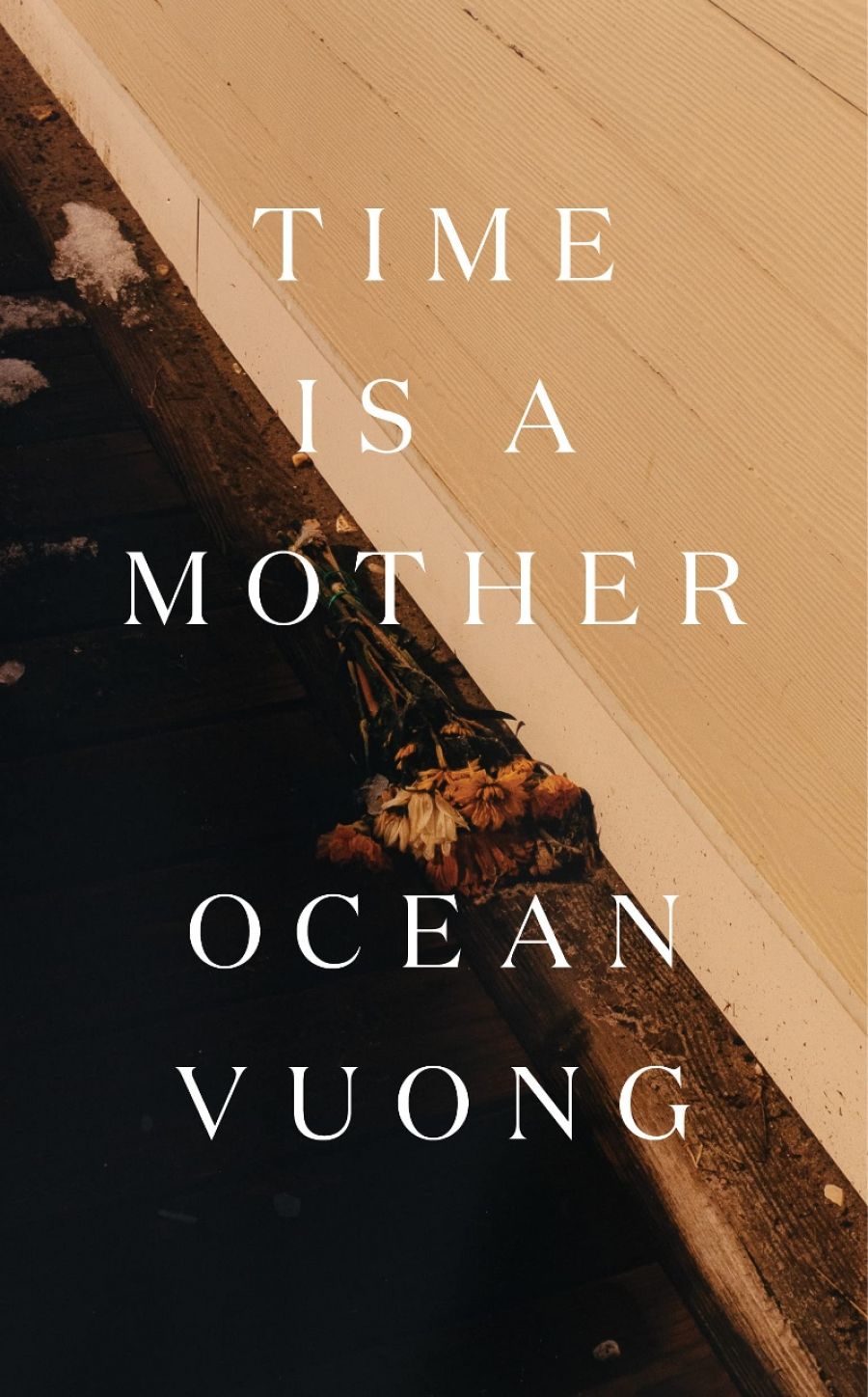

- Book 1 Title: Time Is a Mother

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $24 hb, 84 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4eYbJn

Or, on the hard stuff: ‘I’m not high, officer, I just don’t believe in time’ (‘Beautiful Short Loser’). Like Carson’s ancient Greek lyricists, Vuong is gripped by time’s perversity. Time controls the poet. Does the poet wish to control time? The collection’s penultimate ‘Künstlerroman’ indulges this authorial desire, showing the voyeur–speaker playing the videotape of his life backwards. The opening of the poem flicks through life’s most recent scenes, where ‘[o]ne by one the people hand the man a book, the artifact of his thinking. He opens each one and, pen in hand, traces a deliberately affected signature, until the name, in red evaporates.’

How strange it must be to observe oneself as literary phenomenon. Later in the poem, the speaker watches himself as an Elmo-clutching child. His mother has a job at a clock factory. A child might think their mother goes off to make time. If there is always something we can’t get from our mothers, is that something her time? ‘O mother, // O minutehand,’ apostrophises the speaker in Vuong’s first collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016), recalling Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘I lost my mother’s watch.’ What is this association between mothers and clocks?

It is loss, the poets might say, and mother-losing is central to Vuong’s body of work. As with Roland Barthes, another great mother lover (and a determining force here), writing for Vuong seems less about keeping the presence of the mother than about keeping her absence.

By framing On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019) as a letter to the mother who cannot read, Vuong suggested a text that leans on the space where she is missing. After that elegiac novel, Time Is a Mother seems less like a reckoning with grief than a reprisal of a grief begun prior to her death (Vuong’s mother died of breast cancer shortly after the publication of the novel in 2019). It is novelty and recurrence, impossibly bound at once: ‘Let me begin again now / that you’re gone Ma / if you’re reading this then you survived’ (‘Dear Rose’).

Time Is a Mother elevates loss as a way of holding: ‘What we’ll always have is something we lost’ (‘Snow Theory’). But losing can invite other ingenious strategies, like finding. The found poems are some of the strongest of the collection, demonstrating Vuong’s reputation as a gifted observer. ‘Amazon History of a Former Nail Salon Worker’ shows the mother’s monthly online purchases in the final months of her life. There are anaphoric crescendos – ‘Advil (ibuprofen) 4 pack’ becomes ‘Advil (ibuprofen) Maximum Strength, 4 pack’ – and the desolate caesura, ‘Aug.’, appears with no list. But this is by no means a desolate poem. The mother orders an ‘I Love New York’ T-shirt, a ‘Night Out Red’ lipstick, a chemo scarf in sunrise pink, then in garden print. She is exuberant, fun, sincere. She orders birthday cards for her son, one a pop-up design, the other a Snoopy design that says ‘Son, We Will Always Be Together’. One of my favourite things about Vuong is the dignity with which he treats the aesthetics of the working poor (as here, the aesthetic is often left to speak for itself). It is rare to find art that is so profoundly on the side of this necessary beauty.

Vuong elevates loss another way, giving us the Beautiful Short Loser who is ‘now a professional loser … crushing it in losses’. Losing is winning, an idea that again recalls Bishop. Could we think of this as a (re-)queering of ‘One Art’ (his joking voice, the gesture we love)? ‘Talk about discipline. Talk about good lord.’ Losing is affirming: ‘I can’t believe I lost my tits, he said a minute before, smiling through tears.’ Losing wakes up the voice, invokes poetry: ‘Some call this prayer, I call it watch your mouth.’ Watch your mouth, indeed; is it life philosophy or is it ars poetica? I don’t know but look at this unbelievable line: ‘I used to be a fag now I’m lit. Ha.’ It’s a wild combination, insouciance and restraint compressed in a single line of iambic pentameter. I still don’t know what that decisive ‘Ha’ is doing there, other than to make the tenth syllable. A little nod to the procedure of poetry-making. I love it.

But I didn’t love everything in this collection – a surprise, having loved the previous books very much. ‘They live more!’, a line howled by On Earth’s Little Dog, lives with me rent-free to this day. Vuong’s own lines often live more: ‘It’s true I’m all talk & a French tuck / but so what’; at his best, Vuong is a divine creature of the word. But parts of Time Is a Mother seem to live less: ‘I’m back inside / my head / where it’s safe.’ Some endings feel mawkish with their abject twists: ‘You can be nothing // & still breathing. Believe me’; ‘We’ll only love once / this time.’ It’s painful to see this striving for profundity, even if striving for profundity is the point of lyric poetry. And then life comes back and reprises that good hold: ‘I dog-eared the book & immediately / Thought of masturbation.’

Comments powered by CComment