- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bleak times

- Article Subtitle: The uber-burdens of authorship

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

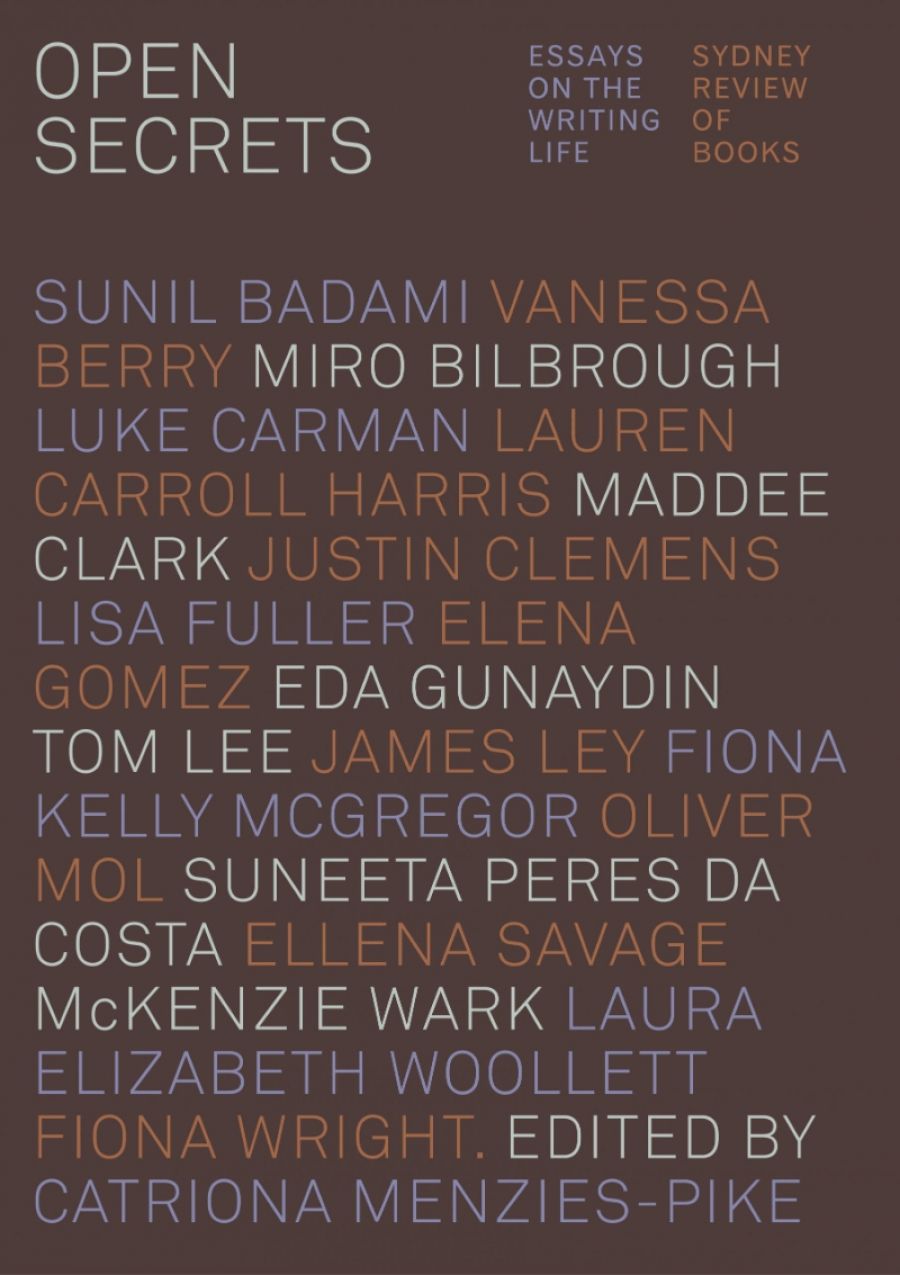

In her introduction to Sydney Review of Book’s latest anthology, Open Secrets: Essays on the writing life, Catriona Menzies-Pike quickly establishes what readers should not expect. ‘There are no precious morning rituals here,’ the editor promises, ‘no magic tricks for aspiring writers.’ It’s true that these essays, each a mix of disarming honesty and polymathic intelligence, hover far above the glut of literary listicles clogging the internet. And thank goodness: if I have to suffer Hemingway mansplaining show-don’t-tell one more time, I may go out and shoot a lion myself.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alex Cothren reviews 'Open Secrets: Essays on the writing life' edited by Catriona Menzies-Pike

- Book 1 Title: Open Secrets

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on the writing life

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney Review of Books, $29.95 pb, 231 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/9W3KL4

There is one piece of advice, however, that fledgling writers may wish to tape above their desk – or pin to their Instagram or whatever. It comes from Fiona Kelly McGregor: ‘the important thing is to prevail’. Each writer has their own burden or obstacle: they are, of course, diverse, from the drudgery of traffic (Luke Carman) to the tedium of email (Justin Clemens) by way of the uber-crushing uber-drudgery of university bureaucracy (James Ley). Maybe not all that diverse, then.

Covid-19 is a constant presence, with many essays clearly written in the grip of the pandemic. ‘I am supposed to be writing this essay,’ repeats Suneeta Peres da Costa, succumbing instead to that familiar lockdown daze, ‘wading into the social slipstream, blithely retweeting quarantine music made by Italians from their apartment windows’.

Fiona Wright, with her usual ferocious wit, unearths the hidden prejudice in that ubiquitous pandemic phrase, ‘new normal’. She points out that ‘disabled people have been asking for workplace flexibility for years’ but that the sudden concessions of the lockdown era only arrived ‘because it was now able-bodied people, normal people, who needed them’. Also on workplace flexibility, and providing one of the collection’s few cheery contributions, Tom Lee imagines a world in which employees break free of their ‘brightly lit, uncomfortable, stifling, energy-intensive, disease-spreading, anxiety-inducing structures’ – aka offices – and instead lounge about in city parks. Lee is, sadly, a visionary before his time: ‘lying down to write or to talk in the office remains transgressive behaviour’.

More than Covid-19 or office etiquette, the biggest obstacle to overcome here is writerly self-doubt, a struggle that Lisa Fuller describes as being ‘trapped in a wave-tossed dinghy: Can I write? No, I can’t! Maybe I can?’ Gather the essays together and they represent the entire life-cycle of a writer’s ego. It begins with ‘a day of writing sentences only to delete them’ (Oliver Mol) which then precipitates ‘guilt at not producing enough’ (Elena Gomez) before lurching into a ‘lightning storm of can’t-eat can’t-sleep productivity’ (Laura Elizabeth Woollett) that satisfies only until ‘Imposter Syndrome makes its obligatory entrance’ (McGregor) and the regular ‘press and thrum of ... worries and neuroses’ return once more (Sunil Badami).

This pressure multiplies under the economic experienced by to the average Australian writer, whose annual income equates to about ten minutes rent in a Sydney shoebox. Even pre-pandemic, public funding of literature has been plummeting as ‘government policies erase or trivialise us’ and the wider public ‘persist in dreamily thinking that our jobs are all dreamy thinking’ (McGregor). As Woollett details in her grimly humorous essay on being shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Award, the best that most contemporary writers can hope for – à la crabs, à la buckets – is a ‘once-in-a-lifetime boon from a government that would prefer we didn’t exist’.

Compounding matters, the few escape boats that have traditionally existed for talented writers are themselves springing leaks. Academia is no good; as Ley writes, ‘We live in a society that is devaluing scholarship in a quite literal sense’ – literal as ‘ripping off sessional teachers while grinding them into the dirt is now part of the business model’. Going freelance seems both romantic and in lockstep with neoliberalism’s lone wolf vibe. In reality, Lauren Carroll Harris says that ‘surviving as a freelancer is like chasing a sheet of sand’. Her essay on short-term contracts is so bleak it could be reworked into a dystopian flick, complete with the perfect tagline: ‘the gig economy doesn’t care whether you live or die’.

It all adds up to what Menzies-Pike describes as ‘a world that measures value in dollars and widgets and accords so little to literature’. A salient point, but one that perhaps sells the rest of the world short. The Irish, for example, are trialling a Universal Basic Income for artists. In Germany, relief to freelancers started flowing as soon as the first Covid cough. Down Under? ‘$660 million for car parks, $125 million for live music’ (McGregor).

Given that Open Secrets exists, it’s no spoiler that the authors prevail here nonetheless, and with aplomb. As such, Menzies-Pike writes that the ‘essays bear witness to the resilience required to commit to the writing life’. Resilience is indeed on display, whether it be the thrifty variety – ‘I can turn three dollars into a nutritious meal,’ brags Ellena Savage in her trademark deadpan – or a deeper dive, like Gomez’s ‘gut level thirst for writing poems’. The resilient artist is a dangerous trope, though, setting up expectations few other workers have to contend with. ‘That’s what they want us to think,’ says Woollett, ‘that our labour has more value when it’s uncompensated.’ No one ever asks a trucker to get by on a gut-level thirst for trucking.

It is therefore a relief to hear Maddee Clark admit that ‘healing coalesces around the pay cheque’ or McGregor warn that ‘being filled with love for my art community ... doesn’t mean you can ask me to work for free’. Writers, this is the only piece of advice you need: ‘Sydney Review of Books pays well’ (McGregor).

Comments powered by CComment