- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Howard’s end

- Article Subtitle: A Booker winner recalls life in Sydney

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A Writer’s Beginnings begins: ‘My mother died today.’ One could be excused for thinking that one was reading not a memoir but a Campus Novel without the ‘p’, an experience that Howard Jacobson will suffer later in this book. Who could read this incipit without hearing the famous beginning: ‘Aujourd’hui maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas.’ Jacobson, on the other hand, knows. He continues: ‘It is 3 May 2020. She is ninety-seven years old.’ I cannot recall whether Albert Camus specifies his protagonist’s mother’s age in L’Étranger (1942). A Camus novel is surely a Campus Novel without the ‘p’, the latter a sub-genre that Jacobson will both live out teaching English at a polytechnic in a defunct football stadium and come to write. Indeed, so insistent is his use of the locution ‘we’ll come to that later’ that one could be excused for thinking prolepsis a Finklerish (see below) rhetorical device. Give Howard Jacobson enough trope and he’ll surely hang himself.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Don Anderson reviews 'Mother’s Boy: A writer’s beginnings' by Howard Jacobson

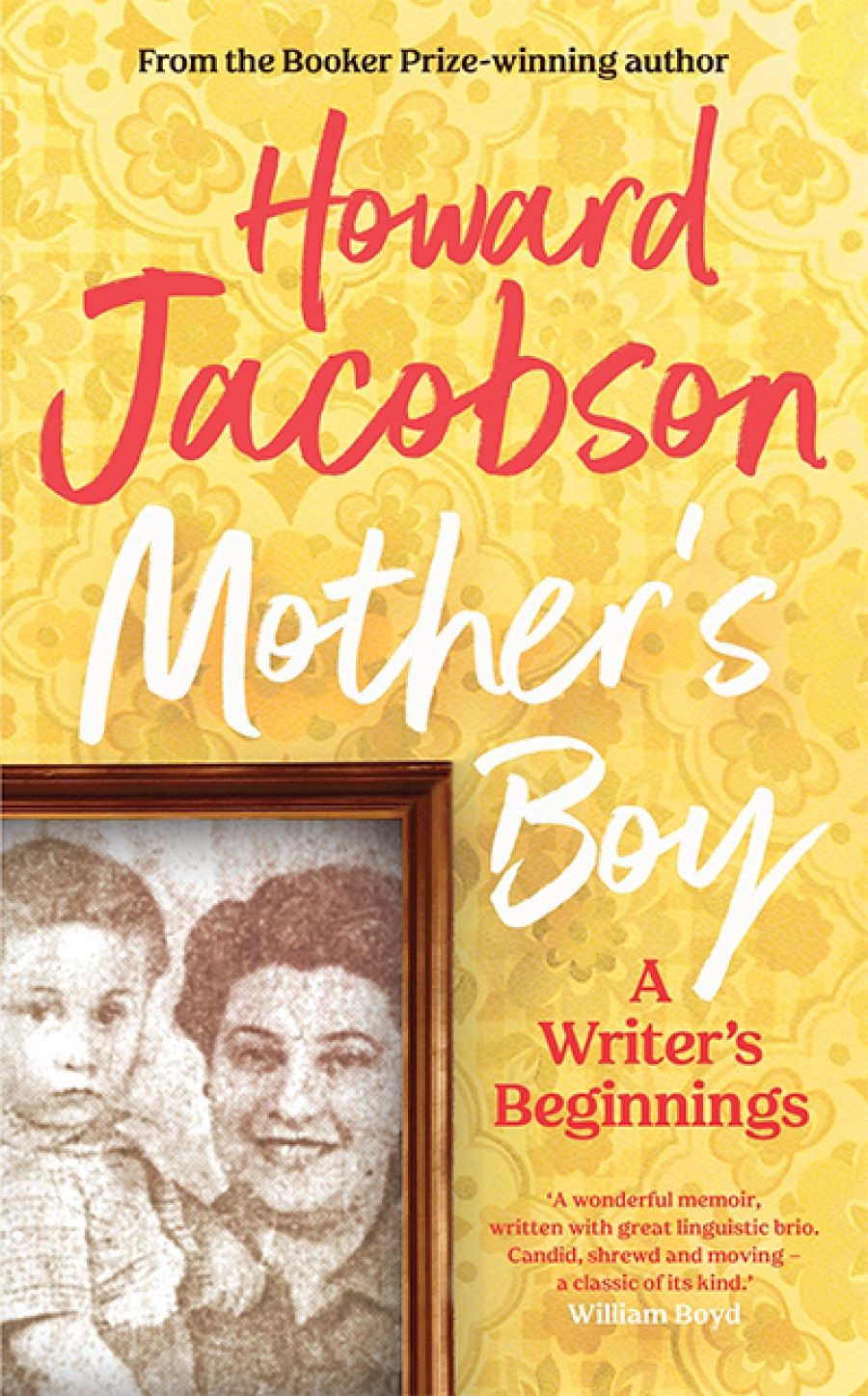

- Book 1 Title: Mother’s Boy

- Book 1 Subtitle: A writer’s beginnings

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $39.99 hb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2r34a0

A good Jewish son is almost by definition a mother’s boy. But Jacobson does not fail to honour his father. ‘My father’s right. I disrespect for the fun of it. Even myself. It’s a species of self-aggrandisement. I see there comes a moment when a confession – especially a confession of cringing cowardice, ineptitude, gracelessness and, I dare even say, Jewish incompetence – risks looking more like a vaunt than a regret.’ But this is a hilarious book, from one-liners such as ‘art was commotion recollected in tranquillity’, pace William Wordsworth, to the representation of oneself as a ‘Finkler’ to purloin the title of Jacobson’s 2010 Booker Prize-winning novel, The Finkler Question. ‘Tell enough lies early enough and you’re bound to end up a novelist.’

Howard Jacobson (photograph by Keke Keukelaar/Penguin)

Howard Jacobson (photograph by Keke Keukelaar/Penguin)

Ending up, or becoming, a novelist is an issue that obsessed Howard Jacobson for his first four decades, when he thought he was doomed to disappointment, until he put it to rest by publishing the perhaps smuttily titled Coming from Behind in 1983. Though he does not mention and would appear not to have known of the Anglo-Irish novelist and colonial official Joyce Cary, he might have taken comfort from the fact that Cary was forty-four when he published Aissa Saved (1932), his first novel, going on to publish twenty more. Cary was once celebrated as the author of the triptych Herself Surprised (1941), To Be a Pilgrim (1942), and The Horse’s Mouth (1944) , the latter filmed in 1958 with Alec Guinness as its artist–protagonist Gulley Jimson, though Cary may be best known today because of Bruce Beresford’s 1990 film of his novel Mr Johnson (1939). Jacobson may perhaps also have taken comfort from Cary’s having graduated from Oxford with a fourth-class degree, though I do recall being informed by an Old Oxonian that this was better than graduating third class. I do not, as a benighted antipodean, pretend to understand this.

Permit me to consider, ‘not dogmatically but deliberately’, Mother’s Boy, as I did Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question back in the December 2010–January 2011 issue of ABR. Jacobson and I were on opposing sides of the Sydney University English Department during the notorious Great Split of the mid-1960s – the days of A-Course versus B-Course, of Sam Goldberg versus G.A. Wilkes, of Leavisite faithful versus ‘eclectic sceptics’. Howard and I even had a public stoush about the relative and doubtless absolute merits and demerits of D.H. Lawrence and Thomas Mann. But that was more than fifty years ago, and besides the wench is dead, as Marlowe hath it. In those years, university humanities departments have suffered the Theory Wars, the Feminist Rewriting of the Dominance of Dead White Males, and the devaluation of the humanities by university administrators and Coalition governments. So, a pax [sic] upon your squabbles. Let us celebrate Jacobson’s survival and successes and agree that his mother would have been proud of him. As would his father.

Although I must admit that Lawrentian-Leavisite expressions such as ‘life-enhancing’ and ‘doing the dirt on life’ still make my flesh creep and raise my hackles, I can enjoy Jacobson’s version of history, of the arrival of S.L. (‘Sam’) Goldberg come to slay the Philistines of Sydney, where he induced Jacobson to join him. Goldberg, ‘a Joyce scholar [there’s at least two ironies in there somewhere] from Melbourne – which it might help to think of, at least in the middle 1960s, as the Athens to Sydney’s Acapulco’, had been ‘charged with the task of waking up what had been a Lotos Land of drowsy, over-tenured beach bums, half-hearted careerists, amateurs and anthologisers who had no time for a sentence such as “The great English novelists are …” on the grounds of its proscriptiveness’, among other things. F.R. Leavis, under whom Jacobson had read English at Downing College, Cambridge, was committed to exclusion as a critical and historical touchstone; this offended if not enraged some of us and underscored our opposition to Sam and his myrmidons. In brief, after a spat somewhat longer than a six-day war, the invaders were routed, retreated to Melbourne, leaving us Lotos Eaters to our anthologising. Ironically, some years later, Shakespeare scholar Howard Felperin was appointed to a chair in Melbourne University’s English Department with a tacit brief similar to Goldberg’s at Sydney – to clean out its Augean stables. He, too, a Finkler.

Note to self: apply to HRC for a grant towards a scholarly paper: the anti-Semitism of academic appointments. But written, let us hope, with Jacobsonian brio.

Comments powered by CComment