- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nationhood on stage

- Article Subtitle: Reassessing the Australian theatrical repertoire

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For at least the first half of the twentieth century, Australian playwrights were not held in high regard by their compatriots. Popular opinion was summed up by fictional theatre manager M.J. Field in Frank A. Russell’s novel The Ashes of Achievement (1920).

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

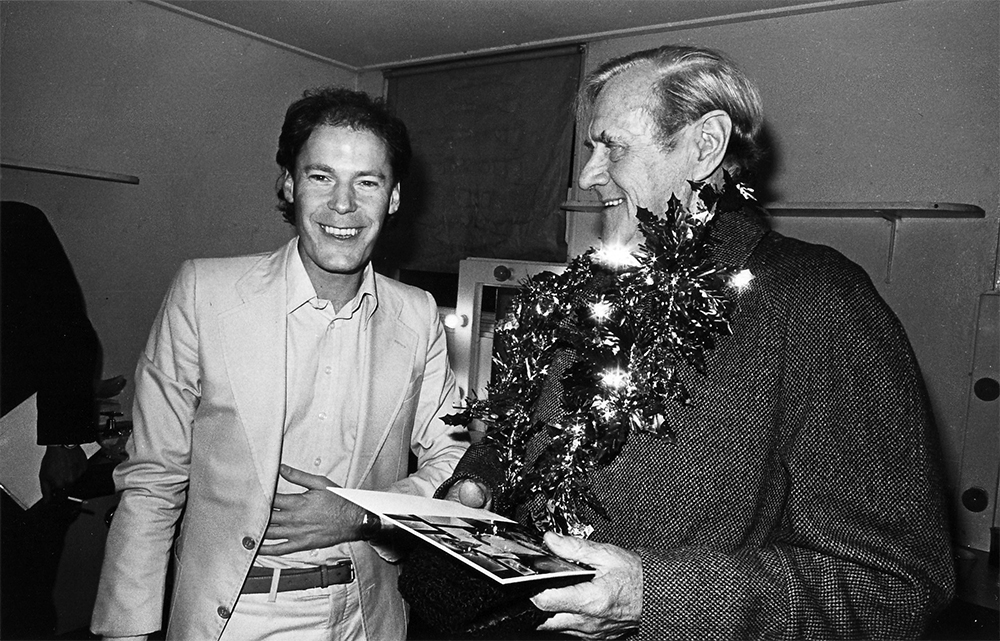

- Article Hero Image Caption: Jim Sharman and Patrick White backstage after the opening-night performance of Big Toys, Parade Theatre, Sydney, 1977 (photograph by William Yang)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Andrew Fuhrmann reviews 'Australia in 50 Plays' by Julian Meyrick

- Book 1 Title: Australia in 50 Plays

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press, $39.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n16qA9

The prejudice was not without foundation. The critic Allan Aldous may have been exaggerating when he complained, in 1947, that Australia had not produced a playwright of consistent competence, let alone greatness, but his exasperation was genuine and had its origin in experience.

This gives a weird fascination to Julian Meyrick’s latest book, in which he tells the history of Australia through an analysis of fifty plays. What sort of reflection should we expect from the cracked looking glass of Australian drama? Meyrick, however, does not dwell on what he calls the professional quality of his chosen plays. What he is interested in are conditions of production and networks of relation.

These fifty plays, therefore, are both emblematic of their moment and have the potential to make the story of Australia more complex and interesting. Relations are established by reading the plays against each other. Descriptions of individual plays accumulate and take on significance where connections to other plays are suggested. It is a kind of quilted tapestry: each play is treated separately but not in isolation, and a larger pattern to which they conform is revealed in differences and repetitions, contrasts and resemblances.

In the early chapters, Meyrick charts the fitful emergence of drama with an Australian setting and mood. The ‘febrile innocence’ of the post-Federation plays evaporates after World War I, and more complex and psychologically troubled characters begin to appear. Gradually, very gradually, the plays become more substantial. Then in 1942, there is a great leap forward, with the première of George Landen Dann’s Fountains Beyond, Dymphna Cusack’s Morning Sacrifice, and the radio version of Douglas Stewart’s Ned Kelly.

Another great leap soon follows, with the première of Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (1955). After the popular success of The Doll, there is a vast increase in the amount of drama in the national repertoire. More than that, there is a greater understanding of how plays might be performed. The quartet of plays by Patrick White that premièred in the 1960s epitomises this turn toward the performative, but the revolution is most often associated with those works lumped under the long banner of New Wave theatre.

The plays of the late 1970s through to the end of the century have a darker and often angrier mood, which Meyrick connects to impacts of the emergent global free market economy on Australian life. The plays of this era register the passing away of one kind of Australia – while interrogating its legacy – but struggle to imagine a new one. Only in the past few decades have playwrights returned to contemplating the future of the nation.

There is an almost epic quality to the way Meyrick negotiates the parallels between these transformations of Australian drama and the flow of contemporary history. Rapid digests of national and world events sit next to descriptions of plays that are grouped by theme or subject matter. And it is from this assemblage that the story – the grand narrative – of the development of Australia’s national consciousness emerges.

This book, then, is an attempt to reassert the concept of nationhood both as a tool for analysing and ordering cultural products, giving them shape and significance, and as a catalyst for meaningful collective action. According to Meyrick, our contemporary view of the concept of nationhood is too negative. A sense of a national life, if taken seriously, provides an imaginative space in which relations across social strata become possible.

The enthusiasm for relations and connections does produce occasional absurdities. For Meyrick, significant affinities between plays are manifest primarily in their deployment of similar character types rather than similar plots or settings. To highlight the development of these types through the decades, Meyrick makes a show of swapping them around like so many dolls in a toy theatre:

The hopeless men in Don’s Party might be younger versions of the hopeless men in Rusty Bugles or, for that matter, in Men Without Wives, now married, but still hopeless. Jane Onslow might have walked out of The Time is Not Yet Ripe, turned serious, and wandered into Crossfire.

For me, at least, the repetition of this device gives an impression of narrowness rather than of depth, as if the repertoire comprised only six characters in search of an Australian who can write drama. But Australia in 50 Plays does not treat the plays only as constituent parts of a modern historical narrative. The summaries of individual plays are a lot of fun. These are not straightforward descriptions of the means by which playwrights have bodied forth the soul of the nation. They are also capsule texts rich in dramaturgical vitamins. Meyrick has interesting and original things to say about almost all the plays featured here, and he can’t help but encourage his readers to dream of brave new theatrical reassessments.

Take, for example, his account of Norm and Ahmed (1968), Alex Buzo’s play about an encounter between a white Australian man and a Pakistani student. Meyrick’s description suggests the possibility of a more thoroughly gothic production than we have seen before: an eerie half-lit world of ghosts and revenants, in which time is suspended and reality is unstable.

This is a book, in other words, that should be in the satchel of every Australian director; it teems with possibilities for an Australian theatre creatively engaged with its repertoire. Even if Meyrick’s primary concern is historiographical, anyone interested in a radical re-engagement with the national drama will understand what he is offering.

Finally, although Australia in 50 Plays is astute about the many ways in which the collective experiences of a nation are registered in its dramatic literature, what it does less convincingly is show how that literature can also influence shared attitudes. I wonder if this is in part because Meyrick, focused as he is on the problems of text and context, has little to say – with one exception – about the ways in which these fifty plays have been produced and how those productions have been received.

It is in the moment of performance that the social force of theatre, its power to shift perceptions, is realised. And the efficacy of that moment depends on so much more than text. Indeed, for a play to galvanise the present and create new subjectivities in its audience, new currents of understanding, the text must disappear behind the shock of its theatrical formulation. But now I am expressing a desire for another sort of book: Australia in fifty performances, perhaps. And once again Meyrick has revealed the desirability of something new, of something that has yet to be done.

Comments powered by CComment