- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Europe’s dowager empress

- Article Subtitle: Maria Theresa and the fate of the Habsburgs

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Few Australians today will have heard of the Empress Maria Theresa (1717–80). And yet this queen of Hungary and Bohemia, archduchess of Austria, ruler of Mantua and Milan, who was also grand duchess of Tuscany and Holy Roman Empress by marriage, bestrode the eighteenth-century stage like a dumpy colossus. The mother of some sixteen children, she styled herself as matriarch for a nation, while the marriages she arranged for her children saw her emerge as a Queen Victoria-like figure: the central node in contemporary Europe’s game of thrones.

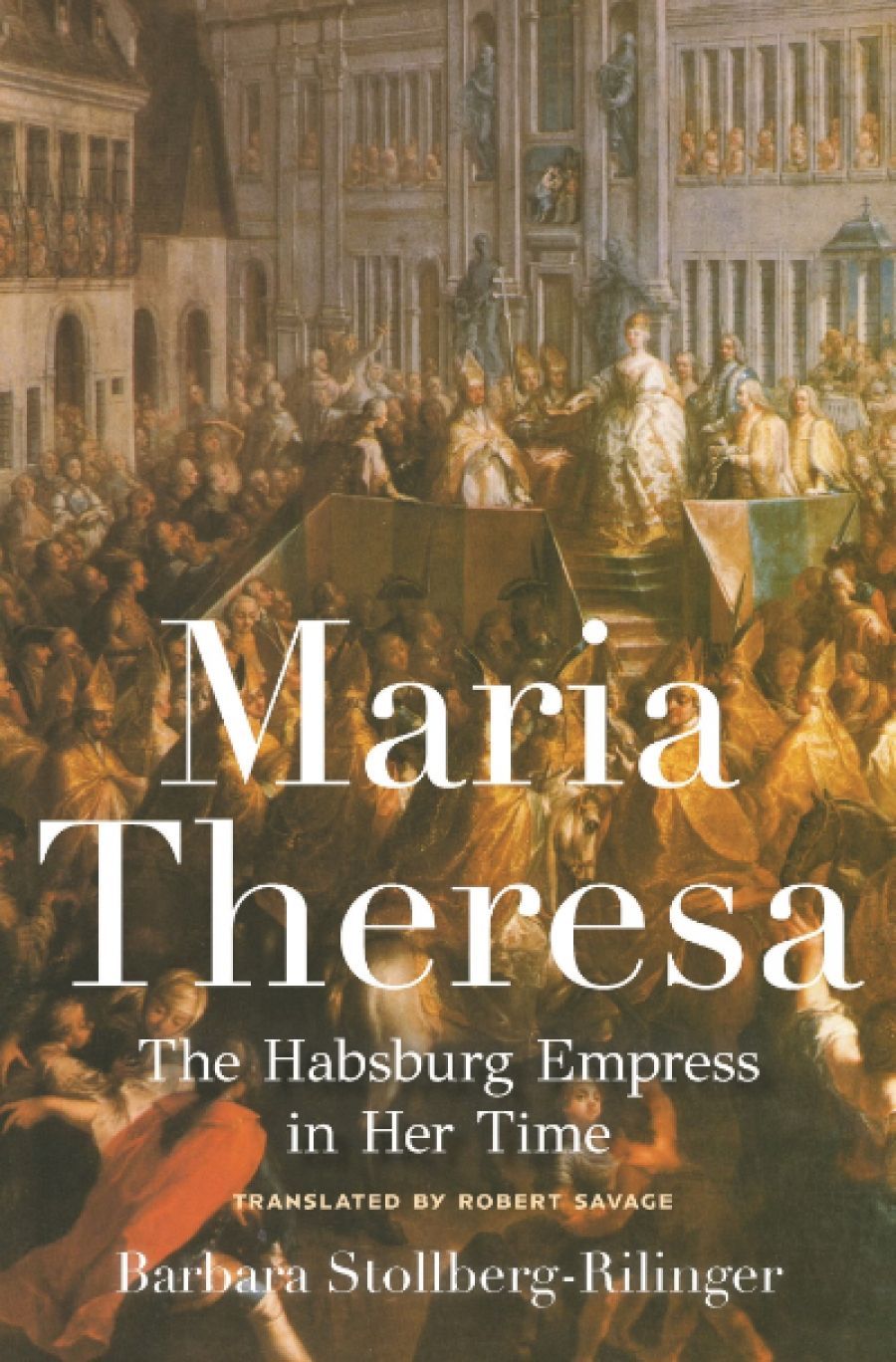

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20copy.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Empress Maria Theresia of Austria, painting by Martin van Meytens, 1759 (Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Miles Pattenden reviews 'Maria Theresa: The Habsburg empress in her time' by Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger, translated by Robert Savage

- Book 1 Title: Maria Theresa

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Habsburg empress in her time

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, $72.99 hb, 1061 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6bM0Xb

In her lifetime, Maria Theresa was an enigmatic figure to her subjects. She secured her father’s throne at great odds – and against the cynical opportunism of most of Europe’s other ruling dynasts – during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). It was said that she was beloved for her beneficence and approachability, yet her court was remote from the lives of most people. The administration she inherited from Emperor Charles VI was also complex, convoluted, and ultimately unfit for purpose – a dense patchwork of local rights and reciprocities between the crown and provincial nobilities which even her most able ministers struggled to modernise. The passage of time, moreover, caused Maria Theresa gradually to fall out of fashion in both élite and intellectual circles. Like the bouffant periwig and her cherished Roman Catholicism, her policies and values soon seemed to have come from a different era. The future, meanwhile, belonged to a more natural, ‘Enlightened’ Weltanschauung, which her eldest son, Emperor Joseph II (1741–90), personified.

Maria Theresa never understood Joseph’s rationalising zeal or his aversion to the archaic court rituals which she had inherited, ultimately, from the Habsburgs’ defunct Spanish line. Mother and son endured a testy relationship in which she could never quite bring herself to relinquish power, while he could not quite bring himself to usurp it. The basic problem was a constitutional conundrum which her status as a female ruler had thrown up. Unable to be Holy Roman Empress in her own right, she arranged for the office to be devolved first onto her husband, Francis Stephen of Lorraine (1708–65), and later onto Joseph. Yet she remained ruler of the Habsburgs’ ancestral lands, which denied both husband and son the resources to enforce their writ as previous emperors had done. Francis Stephen took his diminished status in good humour, but Joseph’s impatience was palpable and spilled out in a decade of quixotic attempts at reform after his mother’s death. That she has much to answer for when it comes to the frustrations and failures of his solo reign is one of this book’s subtexts.

Certainly, Viennese society already viewed the empress as faintly fossilised by the time she expired on 29 November 1780. Only later, as Austria’s international standing deteriorated, was she rehabilitated, such that nineteenth-century Austrians and Germans viewed her and her arch-adversary the Prussian King Frederick II as the twin poles of a collective national psyche: she its defensive, conservative, and feminine element, he the bold, masculine, and aggressive counterpart. Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger’s stated purpose in this biography is to challenge such myths, which she finds unhelpful for an authentic appreciation of the empress’s substantial and, in many ways, quite extraordinary achievements. However, what marks this work out from previous efforts is surely its well-rounded, holistic approach to its subject: chapters on international politics sit alongside others on the empress’s domesticity, religiosity, and physical appearance. Stollberg-Rilinger’s text is long but not excessive in Robert Savage’s attractive translation. Her book could be a model for how such biographies of the great and the good are constructed: a wealth of contextual detail and quirky anecdotes are marshalled in pursuit of a grand vision which becomes more than the sum of its parts.

Certainly, the empress comes alive again in these pages, and the reader will feel that they are being led to appraise her under expert and authoritative tutelage. The chapter on Maria Theresa’s relationship with her husband is particularly fascinating for the humanising agenda it throws up: her need to dominate but also defend him; her jealousy towards his other lovers, but also her strict sexual pragmatism. He, for his part, was determinedly uxorious, a Denis Thatcher figure avant la lettre who picked his battles and remained content to play second fiddle. When he died of a heart attack in 1765, Maria Theresa was genuinely heartbroken, spending the rest of her life in mourning and retreating for part of each month into a contemplative period of solitude.

And yet the great reckoning of Maria Theresa’s reign in Austria is surely that it was a failure, marking the moment when rivals in Russia and Prussia began to eclipse the Habsburg dynasty decisively. So should we not then see the empress as an Angela Merkel figure? In focusing on the rich nuance of Vienna’s court life and politics, Stollberg-Rilinger ends up understating the infelicity of some of her fateful choices, most notably the decision to throw her lot in with Bourbon France. And that begs the question: could she have done otherwise? A different policy would also have denied the world the spectacle of Marie Antoinette as queen of France. Without Maria Theresa’s predilections, the eighteenth century would have had a very different face.

Comments powered by CComment