- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Inhabited space

- Article Subtitle: Subtle edge-work in two new collections

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

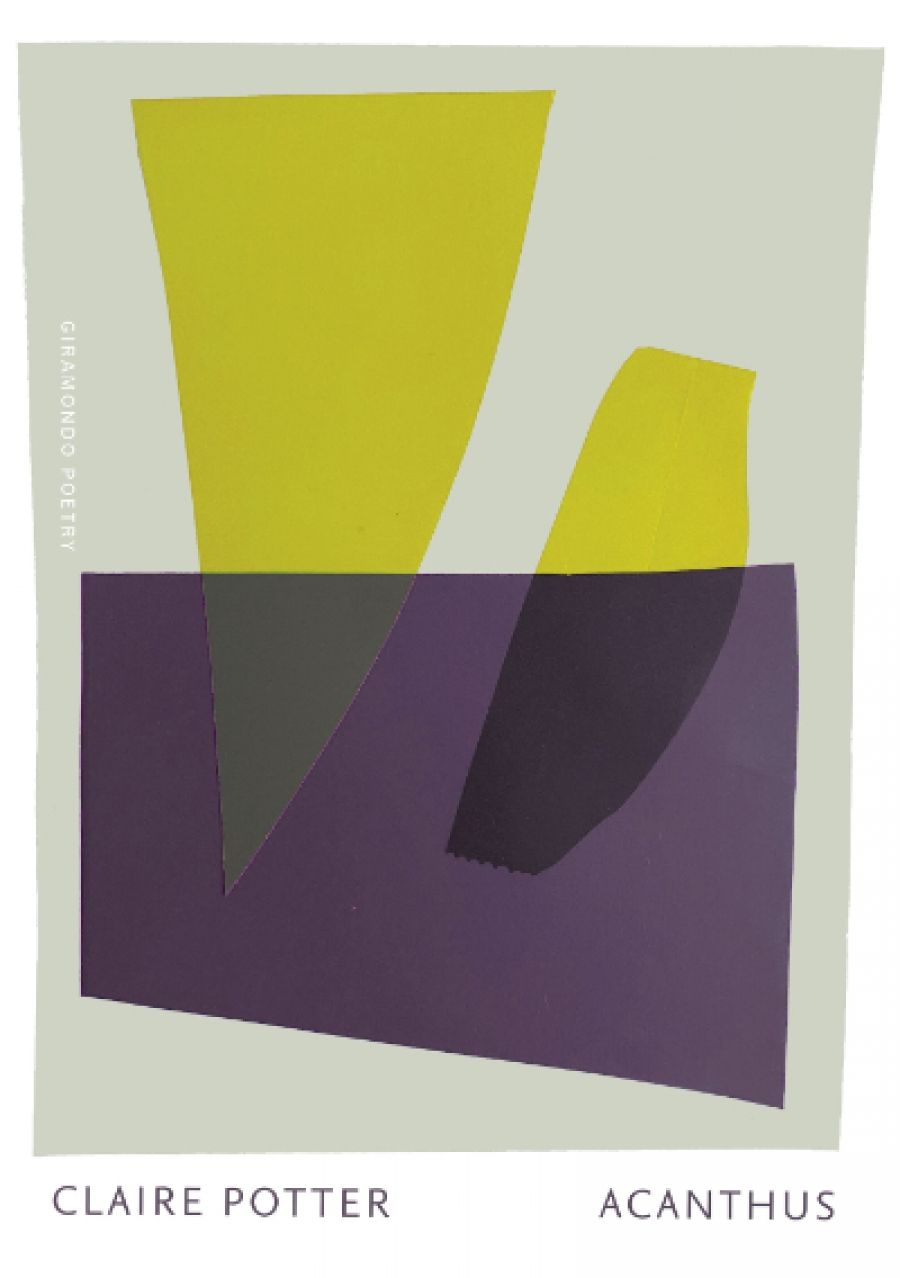

Virginia Woolf, in her seminal essay on modern fiction (1919), might have been describing Claire Potter’s method in her fabulous and highly original new collection: Acanthus. These poems seem to break apart consciousness before it becomes encoded, crystalised, as syntax. As a consequence, they have an uncanny and richly compelling ability to lead you away from the dimension in which you think you have entered the poem, in its opening lines, into something entirely different by the time you have reached the end. Somewhere between the beginning and the end something can be depended on to have shifted – mood, pace, imaginative compass bearing, subject plane.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sarah Day reviews 'Acanthus' by Claire Potter and 'Glass Flowers' by Diane Fahey

- Book 1 Title: Acanthus

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 75 pp

- Book 2 Title: Glass Flowers

- Book 2 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $27 pb, 134 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/May_2022/Glass Flowers.jpg

Potter, born in Australia, has a background in psychoanalysis and teaches writing at the Architectural Association in London. I started to imagine alliances between the two disciplines in the poems, recalling Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (1958) and his axiom that ‘inhabited space transcends geometrical space’. Each of Potter’s spaces, domestic, urban, celestial, leafy, is an opportunity for imagination, memory, and language: a freezing London pond in which the subject is swimming; an apartment in New York in which she is ‘ratcheting [her] fly and running out the door’; the interior of a closed green tulip, peeled backwards, from which she hears ‘only / the silent sequence / of snow-water into wine’. Spaces are porous points of reverie: a bedroom; a chapel; the space ‘within the mess of leaves’ of a fallen copper beech; objects on a desk; the capaciousness of a piece of writing. The positioning of words in the line and of lines on the page, and the frequent use of type spaces and extended dashes, are often integral to the poems’ shaping of edges, external and interior.

‘Three Steps outside the TAB’ is illustrative of Bachelard’s delineation of memory by physical spaces. In this reminiscence, the young child waits all afternoon for her grandfather on the TAB steps which are ‘concrete and absolute / solid and lengthwise between two pillars and a portico’. The steps are both a physical world for the child and a portal for the poet into the site of the child’s intimate narrative.

An extraordinary poem in which human energy transcends the physical space of the room or the house is ‘Eighty-nine Degrees’. Here, sexual desire ignites; the house becomes abstraction, a concept of enclosure for something powerful and immaterial:

A couple trying

to keep to the clock

ill-tempered

in a storm

they stray

undone and fly

across the table

In conveying the energy between two people as living event, this poem is comparable in power to Theodore Roethke’s ‘My Papa’s Waltz’ – once read, never forgotten. At the other end of the emotional arc, the loss of loved ones – a mother, a stillborn infant – is alluded to so weightlessly the poems are like paper nautilus shells.

Potter’s reading is loosely woven into her poems. She alludes to Homer, Heraclitus, Schopenhauer, Barthes, Brodsky, and possibly ‘The Moon-Bone Cycle’ from the Wonguri-Mandjigai people of Arnhem Land, as lightly as she absorbs the vocabulary of sewing into her literary warp and weft: ‘smocking’, ‘thread’, ‘moss-stitch’, ‘tulle’, ‘worsted’, ‘shir’, ‘lacy’, the age-old language of needlework soothes, anchors, domesticates the mythological, the quotidian, and the psychological.

If I had room to quote more of these beguiling poems – ‘Of Bird’s Feet’, ‘Night Chronicle’, ‘Call Them Blueprints of Weather’, ‘After Chopin’, ‘Weeping Foxes’, ‘Room of Clouds’ – it would reveal more of their sensual lustre, the strange quality of silence they contain, and the potent risk of their poetics. These poems enrich one’s experience of the day to day. Potter has the capacity to trap, encase, and breathe time so that it becomes an element the reader can be a part of.

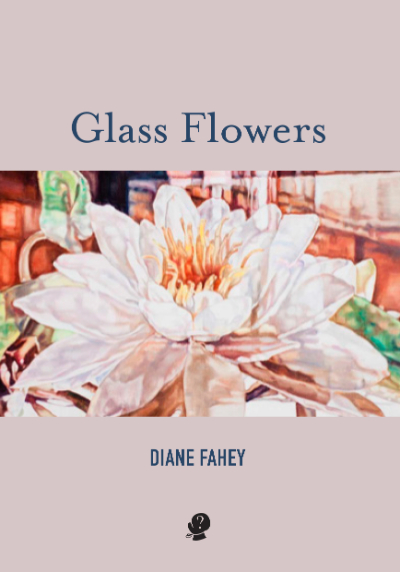

In quite different ways, the architectural – built and organic – inspirits many of Diane Fahey’s poems in her new collection, Glass Flowers. Gardens, galleries, vessels, hospital wards, windows, rooms, ancient caves, skies, and hedges are both subject and genesis for these limpid poems of observation, meditation, and reflection. Fahey is an established and accomplished poet; this is her thirteenth collection of poems. A quintessential observer of the natural world, she does not just notice but notices the process of noticing. The result is focus and stillness.

‘Unearthly’ observes cloud shadows as they pass over oceans, and each other, ‘slide over mountain islands’, cliffs, wheatfields, human lives – to ‘turn our bones wintry’. This long view might be a metaphor for the vagaries of history. Spatial consciousness expands into an even longer view, from satellite perhaps, as darkness extends beyond Earth’s periphery: ‘thousand-mile shadows / cutting through that cold radiance, / probing the void’.

A similar dissolving of the boundaries of physical experience occurs in the next poem, ‘Autumn begins’, a meditation on the moon and cosmological indeterminacy: ‘I can never / in any true way, know what I see.’ With typical spareness, Fahey sums up her relationship with ‘this sky-borne companion’ as ‘intimate remoteness’ – a lovely oxymoron. ‘Cloud Life’ pursues the association between clouds, shadow, light, and transience:

Each day I welcome, now,

whatever light is on offer,

the clouds a parable of how

darkness, radiance, may defer

to each other, even embrace,

even cohabit, then sheer apart …

Delicacy and integrity of perception are encapsulated by brevity in, for example, the gentle and engaging drama that unfolds between gardener and bird, in raindrops ornamenting foliage, or the immaterial: ‘Each human day / a crucible with hairline crack’. ‘Bowers’, an example of Fahey’s treatment of the elusive and transitory, is reminiscent of W.H. Auden’s little gem ‘Their Lonely Betters’; both poems wistfully admire the non-human world for being unencumbered by word and thought. In such poems, my favourites from this section, the emotional presence of the observer is implicitly understood. On occasions, the subject speaker mediates in a way I find obtrusive between poetic subject and reader response, for example: ‘I flow with the blessed air’ or more instructionally: ‘Accept, be blest.’

The final work in this collection, ‘A Death in Winter’ is a sequence of seventeen poems in memory of Leo Seemanpillai, a Tamil refugee to Australia who died in June 2014, ‘after an act of self-immolation’. Fahey’s courageous narrative is unstinting record, witness, apology, prayer, reflection, and, above all, homage to Seemanpillai. The sequence too, looks unflinchingly at how the author, and all of us, live with the sorrow and the shame of such a story. The opening lines suggest a breathing in as Fahey summons the courage to begin: ‘Let me, first, take my bearings / by speaking of weather, the season’. This is a sequence of great breadth and skilful poetic restraint; it encompasses personal grief, respect, moral outrage, and political condemnation, skirting delicately around the edges of despair by its exercise of tenderness and love.

Comments powered by CComment